Reads to reference genome & gene predictions

Introduction

Cheap sequencing has created the opportunity to perform molecular-genetic analyses on just about anything. Conceptually, doing this would be similar to working with traditional genetic model organisms. But a large difference exists: For traditional genetic model organisms, large teams and communities of expert assemblers, predictors, and curators have put years of efforts into the prerequisites for most genomic analyses, including a reference genome and a set of gene predictions. In contrast, those of us working on “emerging” model organisms often have limited or no pre-existing resources and are part of much smaller teams. Emerging model organisms includes most crops, animals and plant pest species, many pathogens, and major models for ecology & evolution.

Please do not jump ahead. You will gain the most by following through each section of the practical one by one.

The steps below are meant to provide some ideas that can help obtain a reference genome and a reference geneset of sufficient quality for ecological and evolutionary analyses. They are based on (but updated from) work we did for the fire ant genome.

Specifically, focusing on low coverage of ~0.5% of the fire ant genome, we will:

- inspect and clean short (Illumina) reads,

- perform genome assembly,

- assess the quality of the genome assembly using simple statistics,

- predict protein-coding genes,

- assess quality of gene predictions,

- assess quality of the entire process using a biologically meaningful measure.

Please note that these are toy/sandbox examples simplified to run on laptops and to fit into the short format of this course. For real projects, much more sophisticated approaches are needed!

Test that the necessary software are available

Run seqtk. If this prints “command not found”, ask for help, otherwise, move to the next section.

Set up directory hierarchy to work in

Start by creating a directory to work in. Drawing on ideas from Noble (2009) and others, we recommend following a specific convention for all your projects.

For the purpose of these practicals we will use a slightly simplified version of the directory structure explained above.

For each practical (analysis) that we will perform, you should:

- have a main directory in your home directory (e.g.,

2020-09-xx-read_cleaning) - have input data in a relevant subdirectory (

input) - work in a relevant subdirectory (

tmp) - copy final results to a relevant subdirectory (

results)

Each directory in which you have done something should include a WHATIDID.txt file in which you log your commands.

Being disciplined about this is extremely important. It is similar to having a laboratory notebook. It will prevent you from becoming overwhelmed by having too many files, or not remembering what you did where.

Sequencing an appropriate sample

Less diversity and complexity in a sample makes life easier: assembly algorithms really struggle when given similar sequences. So less heterozygosity and fewer repeats are easier. Thus:

- A haploid is easier than a diploid (those of us working on haplo-diploid Hymenoptera have it easy because male ants are haploid).

- It goes without saying that a diploid is easier than a tetraploid!

- An inbred line or strain is easier than a wild-type.

- A more compact genome (with less repetitive DNA) is easier than one full of repeats - sorry, grasshopper & Fritillaria researchers!

Many considerations go into the appropriate experimental design and sequencing strategy. We will not formally cover those here & instead jump right into our data.

Part 1: Short read cleaning

Sequencers aren’t perfect. All kinds of things can and do go wrong. “Crap in – crap out” means it’s probably worth spending some time cleaning the raw data before performing real analysis.

Initial inspection

FastQC (documentation) can help you understand sequence quality and composition, and thus can inform read cleaning strategy.

Make sure you have created a directory for today’s practical (e.g., 2020-09-xx-read_cleaning) and the input, tmp, and results subdirectories. Link the raw sequence files (/shared/data/reads.pe1.fastq.gz and /shared/data/reads.pe2.fastq.gz) into input subdirectory:

cd ~/2020-09-xx-read_cleaning

ln -s /shared/data/reads.pe1.fastq.gz input/

ln -s /shared/data/reads.pe2.fastq.gz input/

Run FastQC on the reads.pe2 file (we will get to reads.pe1 later). The command is given below but you will need to replace REPLACE with the path to a directory (this could be your tmp directory) before running the command. The --nogroup option ensures that bases are not grouped together in many of the plots generated by FastQC. This makes it easier to interpret the output in many cases. The --outdir option is there to help you clearly separate input and output files. To learn more about these options run fastqc --help in the terminal.

fastqc --nogroup --outdir REPLACE input/reads.pe2.fastq.gz

Remember to log the commands you used in the WHATIDID.txt file.

Take a moment to verify your directory structure. You can do so using the tree command:

tree ~/2020-09-xx-read_cleaning

Your resulting directory structure (~/2020-09-xx-read_cleaning), should look like this:

2020-09-xx-read_cleaning

├── input

│ ├── reads.pe1.fastq.gz -> /shared/data/reads.pe1.fastq.gz

│ └── reads.pe2.fastq.gz -> /shared/data/reads.pe2.fastq.gz

├── tmp

│ ├── reads.pe2_fastqc.html

│ └── reads.pe2_fastqc.zip

├── results

└── WHATIDID.txt

To inspect FastQC HTML report, copy the file to ~/www/tmp. You can then view the file by clicking on the ~/www/tmp link in your personal module page (e.g., bt007.genomicscourse.com).

What does the FastQC report tell you? (the documentation clarifies what each plot means and here is a reminder of what quality scores means). For comparison, have a look at some plots from other sequencing libraries: e.g, [1], [2], [3].

Clearly, some sequences have very low quality bases towards the end (which FastQC plot tells you that?). Furthermore, many more sequences start with the nucleotide ‘A’ rather than ‘T’ (which FastQC plots tell you that? what else does this plot tell you about nucleotide composition towards the end of the sequences?)

Should you maybe trim the sequences to remove low-quality ends? What else might you want to do?

Below, we will perform two cleaning steps:

- Trimming the ends of sequence reads using cutadapt.

- K-mer filtering using kmc3.

- Removing sequences that are of low quality or too short using cutadapt.

Other tools, such as fastx_toolkit, BBTools, and Trimmomatic can also be useful, but we won’t use them now.

Trimming

cutadapt is a versatile tool for cleaning FASTQ sequences.

We have a dummy command below to trim reads using cutadapt. Can you tell from cutadapt’s documentation the meaning of --cut and --quality-cutoff options? To identify relevant cutoffs, you’ll need to understand base quality scores and examine the per-base quality score in your FastQC report.

Accordingly, replace REPLACE and REPLACE below to appropriately trim from the beginning (--cut) and end (--quality-cutoff) of the sequences. Do not trim too much!! (i.e. not more than a few nucleotides). Algorithms are generally able to cope with a small amount of errors. If you trim too much of your sequence, you are also eliminating important information.

cutadapt --cut REPLACE --quality-cutoff REPLACE input/reads.pe2.fastq.gz > tmp/reads.pe2.trimmed.fq

This will only take a few seconds (make sure you replaced REPLACE).

Now, similarly inspect the paired set of reads (reads.pe1) using FastQC, and appropriately trim them:

cutadapt --cut REPLACE --quality-cutoff REPLACE input/reads.pe1.fastq.gz > tmp/reads.pe1.trimmed.fq

K-mer filtering, removal of short sequences

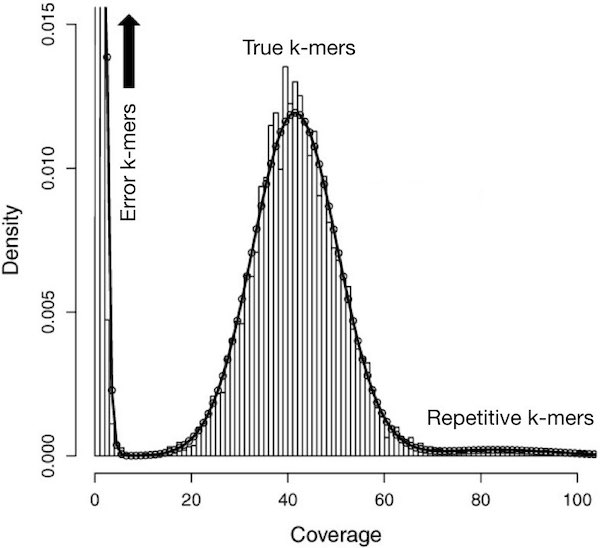

Say you have sequenced your sample at 45x genome coverage. This means that every nucleotide of the genome was sequenced 45 times on average … so for a genome of 450,000,000 nucleotides, this means you have 20,250,000,000 nucleotides of raw sequence. The real coverage distribution will be influenced by factors including DNA quality, library preparation type and local GC content. But you might expect most of the genome to be covered between 20 and 70x. In practice, the distribution can be very strange. One way of rapidly examining the coverage distribution before you have a reference genome is to chop your raw sequence reads into short “k-mers” of, for example, 31 nucleotides, and count how often you get each possible k-mer. An example plot of k-mer frequencies from a haploid sample sequenced at ~45x coverage is shown below:

The above plot tells us the proportion of k-mers in the dataset (the y axis) that have a given count (or, coverage - the x-axis). Surprisingly, many sequences are extremely rare (e.g., present only once). These are likely to be errors that appeared during library preparation or sequencing, or could be rare somatic mutations. Although not shown in the above graph, other sequences may exist at 10,000x coverage. These could be pathogens or repetitive elements. Both extremely rare and extremely frequent sequences can confuse assembly software and eliminating them can reduce subsequent memory, disk space and CPU requirements considerably.

Below, we use kmc3 to “mask” extremely rare k-mers (i.e., convert each base of rare k-mers to ‘N’). This is because we know that those portions of the sequences are not really present in the species. Multiple alternative approaches for k-mer filtering exist (e.g., using khmer). Here, we use k-mer size of 21 nucleotides. Where the masked k-mers are at the end of the reads, we trim them in a subsequent step using cutadapt; where the masked k-mers are in the middle of the reads, we leave them as it is. Trimming reads (either masked k-mers or low quality ends in the previous step) can cause some reads to become too short to be informative. We remove such reads in the same step using cutadapt. Finally, discarding reads (because they are too short) can cause the corresponding read of the pair to become “unpaired”. These are automatically removed by cutadapt. While it is possible to capture and use unpaired reads, we do not illustrate that here for simplicity. Understanding the exact commands – which are a bit convoluted – is unnecessary. It is important to understand the concept of k-mer filtering and the reasoning behind each step.

# To mask rare k-mers we will first build a k-mer database that includes counts for each k-mer.

# For this, we first make a list of files to input to KMC.

ls tmp/reads.pe1.trimmed.fq tmp/reads.pe2.trimmed.fq > tmp/file_list_for_kmc

# Build a k-mer database using k-mer size of 21 nucleotides (-k). This will produce two files

# in your tmp/ directory: 21-mers.kmc_pre and 21-mers.kmc_suf. The last argument (tmp) tells

# kmc where to put intermediate files during computation; these are automatically deleted

# afterwards. The -m option tells KMC to use only 4 GB of RAM.

kmc -m4 -k21 @tmp/file_list_for_kmc tmp/21-mers tmp

# Mask k-mers (-hm) observed less than two times (-ci) in the database (tmp/21-mers). The -t

# option tells KMC to run in single-threaded mode: this is required to preserve the order of

# the reads in the file. filter is a sub-command of kmc_tools that has options to mask, trim,

# or discard reads contain extremely rare k-mers.

# NOTE: kmc_tools command may take a few seconds to complete and does not provide any visual

# feedback during the process.

kmc_tools -t1 filter -hm tmp/21-mers tmp/reads.pe1.trimmed.fq -ci2 tmp/reads.pe1.trimmed.norare.fq

kmc_tools -t1 filter -hm tmp/21-mers tmp/reads.pe2.trimmed.fq -ci2 tmp/reads.pe2.trimmed.norare.fq

# Trim 'N's from the ends of the reads, then discard reads shorter than 21 bp, and save remaining

# reads to the paths specified by -o and -p options. -p option ensures that only paired reads are

# saved (i.e., orphans are discarded).

cutadapt --trim-n --minimum-length 21 -o tmp/reads.pe1.clean.fq -p tmp/reads.pe2.clean.fq tmp/reads.pe1.trimmed.norare.fq tmp/reads.pe2.trimmed.norare.fq

# Finally, we can copy over the cleaned reads to results directory for further analysis

cp tmp/reads.pe1.clean.fq tmp/reads.pe2.clean.fq results

Inspecting quality of cleaned reads

Which percentage of reads have we removed overall? (hint: wc -l can count lines in a non-gzipped file). Is there a general rule about how much we should be removing?

Run fastqc again, this time on reads.pe2.clean.fq. Which statistics have changed? Does the “per tile” sequence quality indicate to you that we should perhaps do more cleaning?