Ants, Bees, Genomes & Evolution @ Queen Mary University London

Published: 30 June 2011

The genome of the leaf-cutting ant Acromyrmex echinatior suggests key adaptations to advanced social life and fungus farming

S. Nygaard, G. Zhang, M. Schiott, C. Li, Y. Wurm, H. Hu, J. Zhou, L. Ji, F. Qiu, M. Rasmussen, H. Pan, F. Hauser, A. Krogh, CJP Grimmelikhuijzen, J. Wang, JJ. Boomsma

Genome Research, 2011, 21:1339-1348

Abstract

We present a high-quality (>100× depth) Illumina genome sequence of the leaf-cutting ant Acromyrmex echinatior, a model species for symbiosis and reproductive conflict studies. We compare this genome with three previously sequenced genomes of ants from different subfamilies and focus our analyses on aspects of the genome likely to be associated with known evolutionary changes. The first is the specialized fungal diet of A. echinatior, where we find gene loss in the ant’s arginine synthesis pathway, loss of detoxification genes, and expansion of a group of peptidase proteins. One of these is a unique ant-derived contribution to the fecal fluid, which otherwise consists of “garden manuring” fungal enzymes that are unaffected by ant digestion. The second is multiple mating of queens and ejaculate competition, which may be associated with a greatly expanded nardilysin-like peptidase gene family. The third is sex determination, where we could identify only a single homolog of the feminizer gene. As other ants and the honeybee have duplications of this gene, we hypothesize that this may partly explain the frequent production of diploid male larvae in A. echinatior. The fourth is the evolution of eusociality, where we find a highly conserved ant-specific profile of neuropeptide genes that may be related to caste determination. These first analyses of the A. echinatior genome indicate that considerable genetic changes are likely to have accompanied the transition from hunter-gathering to agricultural food production 50 million years ago, and the transition from single to multiple queen mating 10 million years ago.

Active food production through farming is a landmark of human cultural evolution (Diamond 2002), but has also evolved in a diverse array of other organisms purely by natural selection (Mueller et al. 2005; Boomsma 2011). Some of these represent forms of husbandry (e.g., Dictyostelium slime moulds) (Brock et al. 2011) or lack control over crop transmission (Littoraria snails) (Silliman and Newell 2003, and Stegastes damselfish) (Hata et al. 2010). Others, such as the multiple lineages of ambrosia beetles have evolved more complex fungus-farming systems, with extensive cotransmission and mutual coadaptation between farmers and crops (Farrell et al. 2001). However, only the fungus-growing ants and termites have developed large-scale societies that are completely dependent on specific fungal symbionts for producing most of their food (Schultz et al. 2005; Aanen et al. 2009).

The fungus-growing ants have become an ecological and evolutionary model system of major importance. Just as in the macrotermitine termites (Aanen et al. 2002), attine ant fungus farming has a single origin ∼50 MYA ago in South America (Schultz and Brady 2008). The transition to active food production was so successful that the tribe presently has at least 220 species in 11 generally recognized genera, without any known case of successful reversion to a hunter–gatherer lifestyle (Schultz and Brady 2008). The crown group of the Atta and Acromyrmex leaf-cutting ants in particular stands out as an impressive example of social evolution. The common ancestor of these ants lived only 10 million years ago and achieved several major evolutionary transitions roughly at the same time (Villesen et al. 2002), including: (1) large-scale use of live plant material to manure fungal gardens; (2) extensive differentiation of worker castes to optimize division of labor in foraging and conveyor-belt processing of leaves, flowers, and fruits; (3) long-lived colonies with tens of thousands of workers in Acromyrmex, and some millions in Atta; (4) multiple mating of queens, most likely to ensure higher genetic diversity among workers, enabling more robust collective performance and higher resistance toward infectious disease (Hughes and Boomsma 2004, 2006).

Several draft genomes of ants have recently become available (Bonasio et al. 2010; Wurm et al. 2011), addressing some of the fundamental genomic changes that accompanied the evolution of eusocial colony life. These analyses generally use the genome of the honeybee, representing an independent hymenopteran lineage that evolved eusocial organization (Honeybee Genome Sequencing Consortium 2006), and three species of Nasonia parasitoid wasps (Werren et al. 2010) for comparison. With the present study we add another ant genome to the publicly available databases, providing some comparisons with the genome of the fire ant Solenopsis invicta (Wurm et al. 2011), which belongs to the same subfamily (Myrmicinae) as Acromyrmex, and with representatives of two other ant subfamilies: Ponerinae and Formicinae (Bonasio et al. 2010). However, the major interest of sequencing the genome of Acromyrmex echinatior is that this Panamanian ant species is a model system for many key questions in evolutionary ecology, which will become accessible for genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic studies now that a reference genome is available.

Many aspects of the biology of A. echinatior have become documented in recent years: (1) All queens mate with many males so that colonies are always chimaeras of approximately five to 15 patrilines (Sumner et al. 2004). Competition between ejaculates mediated by seminal fluid interactions has been demonstrated (Den Boer et al. 2010), providing interesting opportunities for elucidating the molecular mechanisms involved in sperm competition. (2) Caste differentiation into small workers, large workers, and gynes (future queens) is phenotypically plastic (Hughes et al. 2003; Hughes and Boomsma 2004), but some of the rare patrilines cheat by being over-represented among the new queens that a colony produces, either in association with over-representation among the small workers or the large workers (Hughes et al. 2003; Hughes and Boomsma 2008). (3) The species is facultatively polygynous and has a closely related inquiline social parasite, Acromyrmex insinuator, which shares a direct common ancestor with its host (Schultz et al. 1998; Bekkevold and Boomsma 2000; Sumner et al. 2003a,b, 2004). (4) Explicit studies on the heritability of disease resistance have shown that the genetic diversity emanating from multiple queen-mating is likely to be adaptive (Hughes and Boomsma 2004, 2006, 2008). (5) The fungal symbionts of this species are known to express incompatibilities both when unrelated mycelia interact directly and when the fecal droplets that the ants use to manure their gardens come into contact with alien garden symbionts (Bot et al. 2001; Poulsen and Boomsma 2005; Ivens et al. 2009). (6) A substantial proportion of fungal enzymes and other proteins are not digested by the ants, but deposited with the fecal droplets and mixed with the new leaf substrate in the growing top sections of fungus gardens (Schiøtt et al. 2008, 2010), indicating that the obligate dependence on a fungal symbiont has induced prudent harvesting practices that are likely to have left genomic signatures. (7) Haplodiploid sex determination normally implies that there are one or several sex-determining loci of high heterozygosity (Hasselmann et al. 2008), so that homozygote individuals meant to be females develop as sterile diploid males. A. echinatior queens are known to produce many diploid male larvae, but workers remove them early in development (Dijkstra and Boomsma 2007). This implies that detailed knowledge of sex-determination genes in this species, relative to social insects that do not suffer high potential fitness loads due to diploid male production, will be rewarding. (8) Leaf-cutting ants have undergone major changes in behavior and physiology after they adopted fungus farming relative to their ancestors that have remained hunter–gatherers. Neuropeptides play essential roles in information processing at all metabolic levels (Hauser et al. 2010), so that genomic analyses of these key substances might provide important insights.

The objective of this study was, therefore, to probe the A. echinatior genome for the key aspects of biological function outlined above. In particular, we provide in-depth analyses of detoxification pathways in relation to homogeneous fungal food, arginine biosynthesis, peptidase gene family expansions, neuroendocrinology, and the sex-determining locus.

Results and Discussion

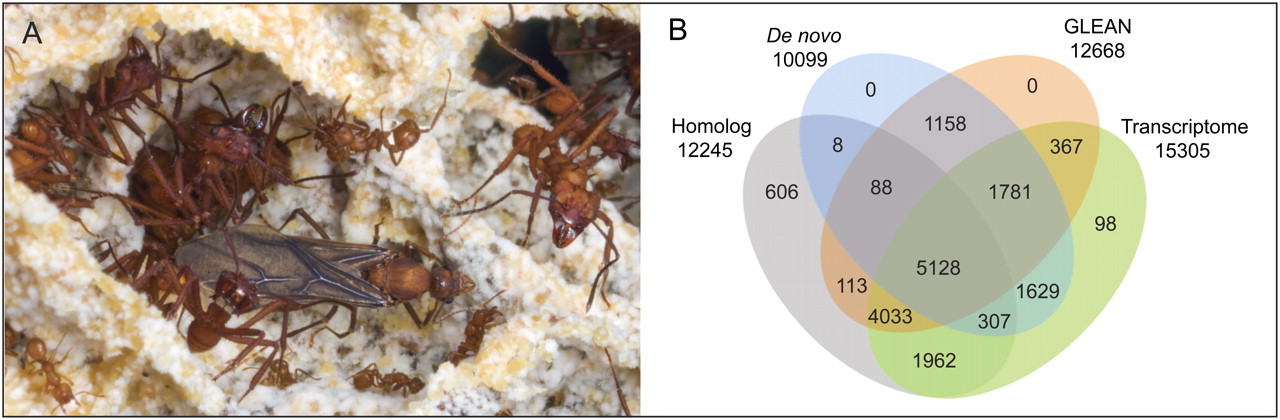

The genome of A. echinatior (Fig. 1A) was obtained using the Illumina HiSeq platform, which yielded 60.7 Gb of raw reads from males of a single colony, and assembled with SOAPdenovo (Li et al. 2010), generating 300 Mb of assembled genome sequence (see Supplemental Tables S1, S2). The N50 scaffold length is 1.1 Mb, longer than reported for other ant genomes (Supplemental Table S3), with an average sequencing depth of 123 × (Supplemental Fig. S1), ensuring high accuracy at the nucleotide level.

Figure 1.

The leafcutter ant A. echinatior and annotation of its protein-coding genes. (A) A winged male of the Panamanian leaf-cutting ant A. echinatior in the fungus garden that is maintained by his major- and minor-worker sisters. (B) The total of 17,278 annotated protein-coding genes as obtained from de novo predictions, GLEAN acceptance, homology (to C. *floridanus*, H. saltator, A. mellifera, N. vitripennis, D. melanogaster, C. elegans, or H. sapiens) and transcriptome evidence. (Photo courtesy of David R. Nash © 2010.)

Using flow cytometry, the total genome size of A. echinatior has previously been estimated to be 335 Mb (Sirviö et al. 2006). Based on k-mer coverage (Li et al. 2009a), we get a similar estimate of 313 Mb, suggesting that the assembled genome is 96% complete. Any missing regions are likely to consist of repetitive sequences that cannot easily be assembled with current methods. The A. echinatior genome is AT-rich, with a GC content of 46.9% in protein-coding exons, and an overall GC content of 33.7%. Both genome size and GC content were within the range reported for other ant genomes (Supplemental Table S3; Bonasio et al. 2010; Wurm et al. 2011). A total of 27.6% (82.6 Mb) of the sequenced genome was classified as repetitive sequence, based on both known and ab initio repeat libraries (Supplemental Table S4), an estimate close to the recently published sequence data for the ponerine ant Harpegnathos saltator (Bonasio et al. 2010), but lower than the more closely related S. invicta genome (Wurm et al. 2011) and higher than that of Camponotus floridanus (Supplemental Table S3; Bonasio et al. 2010).

Transcript data were obtained by Illumina sequencing of RNA from a pooled sample of different castes and developmental stages. We then annotated 17,278 protein-coding genes by using GLEAN (Elsik et al. 2007) to integrate de novo gene predictions, transcriptome evidence, and BLAST (Altschul et al. 1997) homology information. Eighty-four percent of the annotated genes were supported by transcript evidence, and 70% showed homology with known genes in other species (Fig. 1B; Methods). We manually verified more than 200 of the gene models.

To assess the completeness of the annotation, we used the CEGMA (Parra et al. 2007) set of 458 core eukaryotic genes. Almost all of these (449; 98%) were found in our gene set, again confirming the completeness of the genome. We furthermore annotated 316 predicted tRNA genes, 58 rRNA genes, 29 snRNAs, and 93 miRNAs (Supplemental Table S5). The latter is close to the number of miRNAs reported in C. floridanus (96) (Bonasio et al. 2010), although more extensive sequencing of short RNAs may increase this number further. BLAST searches revealed some contigs/scaffolds of bacterial origin (Supplemental Table S6). Most notably, we saw evidence of two strains of Wolbachia endobacteria in A. echinatior, consistent with previous findings (Van Borm et al. 2003).

Genomic analyses and comparisons across the ant phylogeny

To assess the functional changes that have occurred in A. echinatior during its specialization to a fungus-farming life style, we compared the predicted genes of A. echinatior with those of three other ants: S. invicta, C. floridanus, and H. saltator, as well as to the more distantly related honeybee (Apis mellifera), parasitoid wasp (Nasonia vitripennis), and fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster). For each genome, we assigned gene function (see Methods), followed by gene clustering across all species. This generated 11,848 gene families, 1995 of which contained exactly one sequence from every species. Fourfold degenerate codon positions were extracted from these and used to construct a phylogenetic tree with PhyML (Supplemental Fig. S2; Guindon et al. 2009), confirming that the two ants of the subfamily Myrmicinae (A. echinatior and S. invicta) are most closely related, followed by C. floridanus and H. saltator, as expected from presently available phylogenies of all ants (Brady et al. 2006; Moreau et al. 2006).

We calculated gene ontology (GO) enrichment in A. echinatior-specific genes, in myrmicine subfamily-specific gene families (containing sequences from both A.echinatior and S. invicta, but not from H. saltator or C. floridanus), and in gene families where the homolog has been lost by A. echinatior (sequences from both S. invicta and at least one of H. saltator and C. floridanus, but not A. echinatior). For the latter group, we verified the absence of A. echinatior homologs by realigning sequences from the gene families to the assembly. The only GO category enriched in A.echinatior-specific genes was “transition metal ion binding” (Supplemental Table S7), whereas GO categories associated with CD27 receptor binding, transferase activity, and nucleic acid binding were enriched in the Myrmicinae-specific gene families. In the gene families where A. echinatior has lost homologs, enriched categories included spliceosome assembly and zinc ion binding (Supplemental Table S7).

Analysis of gene family expansion or contraction allows inferences about the particular challenges that a species has faced or been released from over evolutionary time. We used the phylogenetic gene family modeling pipeline CAFE (De Bie et al. 2006) to identify significantly (P < 0.001) expanded or contracted gene families in A. echinatior and/or S. invicta myrmicine ants, relative to the other eusocial hymenopteran genomes (Supplemental Fig. S3). Of the 5134 gene families that contained at least one sequence from each of these five genomes, 10 were specifically expanded in A. echinatior, and another 10 were contracted (Supplemental Table S8). Four families were found to be expanded in both representatives of the Myrmicinae, and three were contracted (Supplemental Table S9).

Families of olfactory receptors were identified among the contracted gene families in both A. echinatior and S. invicta, although olfactory receptors have generally been expanded in ants (Bonasio et al. 2010; Wurm et al. 2011). However, these genes are difficult to annotate automatically, so more work will be needed to interpret these differences, as it is possible that other subfamilies of these receptors have expanded to compensate for losses elsewhere. Some other expanded or contracted gene families were examined in more detail, and will be discussed in the sections below.

Changes in detoxification pathways

Insects harbor a range of enzymes to catalyze the detoxification and neutralization of toxins that are ingested with food or otherwise encountered in the environment. It has previously been reported that ants, in particular C. floridanus, show an expansion of detoxification-related genes, which was attributed to their typical life style as generalized predators, aphid herders, and scavengers (Bonasio et al. 2010). Since leafcutter ants rely on a symbiotic fungus as an almost exclusive food source, it would seem plausible that they ingest fewer toxins, and thus need a smaller repertoire of detoxification genes. We assessed whether any such adaptations might have evolved by comparing the number of genes with predicted protein domains corresponding to different central classes of detoxification enzymes across the ants for which genomic information is available (Supplemental Table S10).

We found a marked reduction in the number of cytochrome P450 monooxygenase genes: A. echinatior only has 73 genes predicted to contain the CytP450 domain, while the other investigated ants have 95–132. This reduction of CytP450 containing genes in A. echinatior resembles the low number (60) observed in the honeybee, which also lives on a specialized diet of toxin-free food. Less-pronounced reductions were found in the number of genes containing the carboxy/cholinesterase and UDP-glucoronosyltransferase domains (Supplemental Table S10). In contrast to these reductions, the number of gluthathione S-transferase genes appears slightly higher in A. echinatior than in other ants or the honeybee.

Arginine metabolism

Obligate mutualistic symbioses with a history of 50 million years (Schultz and Brady 2008) can be expected to have evolved some degree of division of labor in the acquisition of essential amino acids. This is particularly likely because Acromyrmex and Atta leafcutter ants rear a highly derived and specialized fungal symbiont throughout their range (Mikheyev et al. 2008). Examples from other symbioses showing similar adaptions are Euprymna squid supplying their symbiotic bioluminescent Vibrio bacteria with amino acids to support their growth (Graf and Ruby 1998) and aphids relying on Buchnera endosymbiont to provide essential amino acids (Klasson and Andersson 2004). Camponotus ants are also known to rely on intracellular Blochmannia bacteria for the production of essential amino acids (Feldhaar et al. 2007).

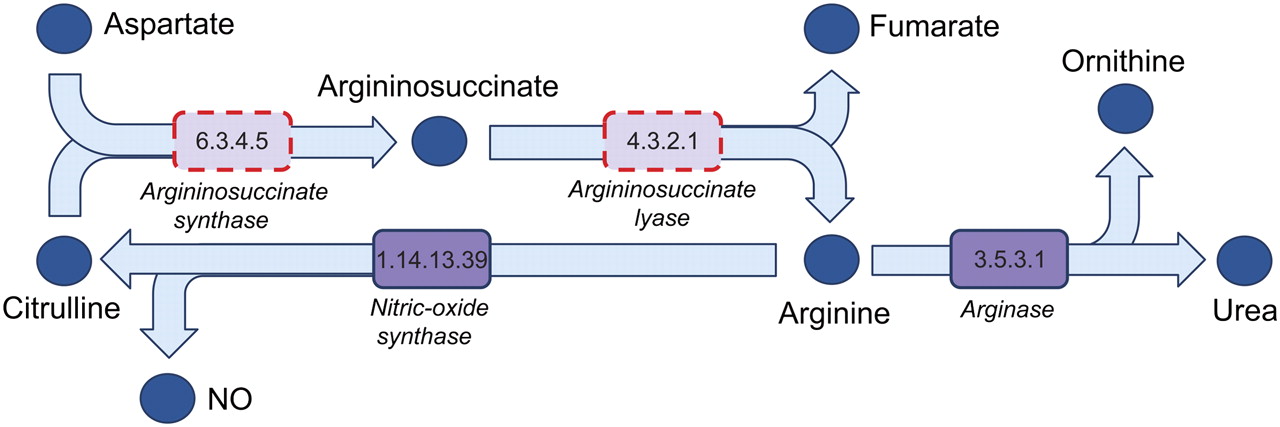

We used BLAST (Altschul et al. 1997) to assign genes to functional categories defined in the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG categories) (Kanehisa and Goto 2000) and examined the annotations to identify metabolic pathways where A. echinatior had an apparent loss-of-function compared with the other three ants for which genomes were available: S. invicta, C. floridanus, and H. saltator. We found that two genes involved in arginine biosynthesis appear to have been specifically lost in A. echinatior: Argininosuccinate synthase (EC:6.3.4.5), which catalyzes the conversion of aspartate and citruline into argininosuccinate, and argininosuccinate lyase (EC:4.3.2.1), which catalyzes the subsequent conversion of argininosuccinate to arginine and fumarate (Fig. 2). These losses are not due to missing sequence data in the genome that we obtained, as we were able to identify the pseudogene for argininosuccinate synthase (Supplemental Table S11). This is consistent with the evolution of a significant metabolic division of labor between the ants and their fungal crop, as functional arginine pathways appear to be present in the related Agaricales fungi Laccaria bicolor and Coprinopsis cinerea (KEGG, release 56.0).

Figure 2.

Missing genes in the arginine biosynthesis pathway. The specific loss in A. echinatior of two genes that encode enzymes catalyzing two consecutive (final) steps in the biosynthesis of the amino acid arginine. Enzymes are denoted by purple boxes with the EC numbers inside. Pale purple boxes with dashed red borders indicate the two lost or pseudogenized genes.

Expansion of peptidase gene families

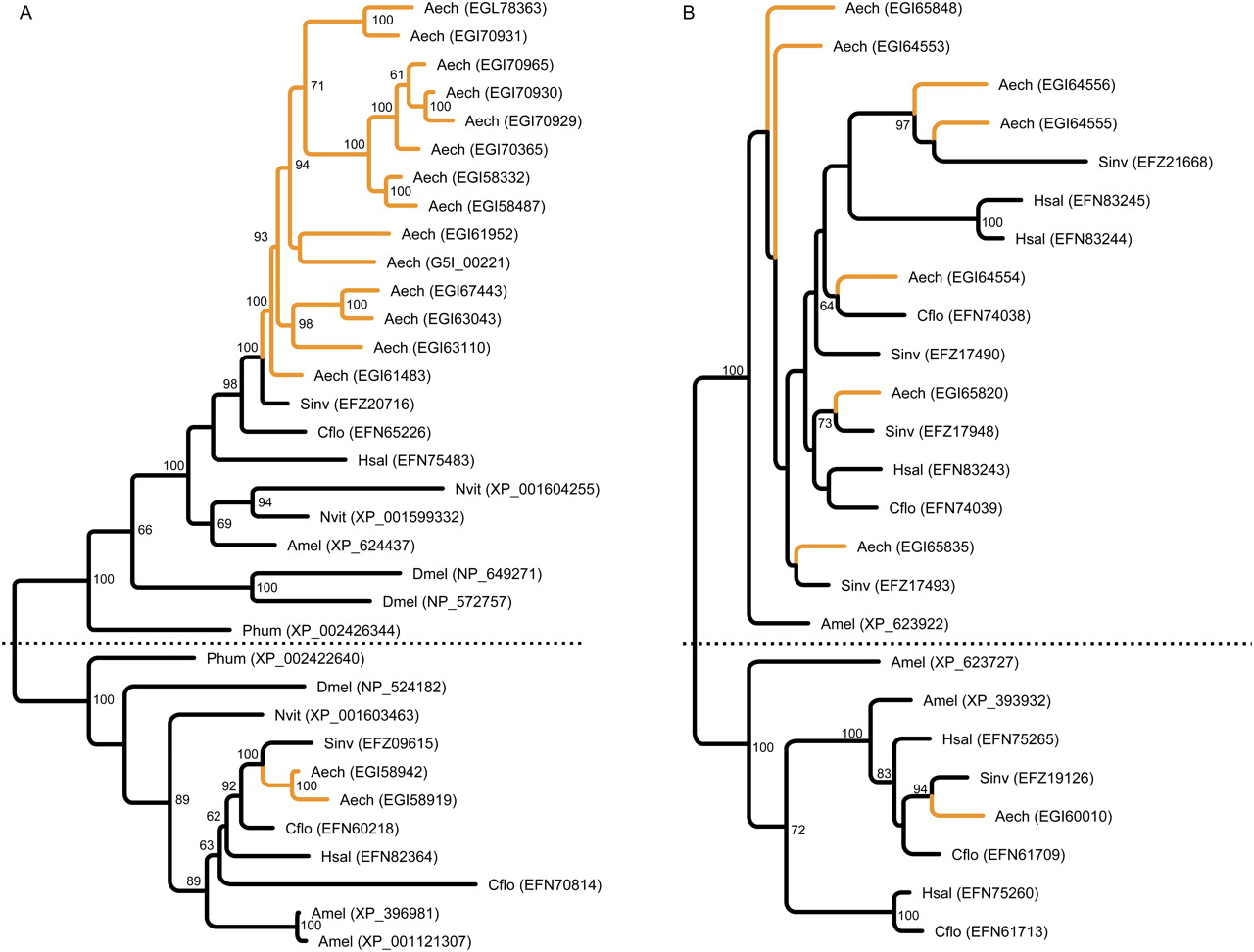

The most pronounced expansion was observed in a family of predicted peptidase M16 genes, where A. echinatior has 16 members, while the other investigated Hymenoptera have two (S. invicta, H. saltator) or three (A. mellifera, C. floridanus, N. vitripennis). The phylogenetic tree of this gene family (Fig. 3A) shows that the genes cluster in two groups. One group contains genes that encode proteins similar to insulin degrading enzymes, and has only one to two members in all insect genomes investigated, while the other group contains genes encoding proteins similar to nardilysin, and it is this group that is greatly expanded in A. echinatior. Peptidase M16 proteins have a conserved motif with the amino acid sequence HXXEH, which is believed to be the active site (Becker and Roth 1992). However, most of the extra M16 proteins in A. echinatior seem to lack this motif, so it is possible that they no longer function as active peptidases.

Figure 3.

Peptidase expansions in the genome of A. echinatior. (A) Expansion of the M16 peptidase gene family with the insulin degrading enzyme, present in one or two copies in all investigated insect genomes (below dotted line), and nardilysin genes (above dotted line). The A. echinatior genes in each group are highlighted in yellow. Bootstrap support values >60% are given. (B) Expansion of the M14 peptidase gene family, with a dotted line separating two subfamilies. The A. echinatior genes are highlighted in yellow. Bootstrap support values >60% are given. Phum was included to increase resolution of this tree. Species (A. echinatior: Aech; H. saltator: Hsal; C. floridanus: Cflo; S. invicta: Sinv; A. mellifera: Amel; D. melanogaster: Dmel; N. vitripennis: Nvit; Pediculus humanus: Phum) and GenBank ID are given for each sequence.

Nardilysin from rats has been shown to cut peptides at dibasic sites, suggesting a prohormone convertase function, i.e., cleaving a prohormone target into mature hormone(s) (Chesneau et al. 1994). Mammalian nardilysin is particularly abundant in the adult testes (Hospital et al. 1997; Fumagalli et al. 1998), and one of the two homologous genes in D. melanogaster is highly expressed in the testes and the male accessory glands (www.flyatlas.org) (Chintapalli et al. 2007). It is thus tempting to speculate that the M16 expansion in A. echinatior has some connection to the high degree of multiple queen mating and the ensuing ejaculate competition after insemination, as the other ants used in our analysis appear to have singly mated queens (Boomsma et al. 2009; Den Boer et al. 2010). The nardilysin gene group is not expanded in the honeybee, which also has multiple queen mating, but many other genes known to be involved in the sperm and accessory gland secretion of Apis honeybees (Baer et al. 2009a, b) are also present in A. echinatior (Supplemental Tables S12, S13). This suggests that many key elements of sperm transfer and sperm storage are conserved and have been maintained in two hymenopteran clades, where multiple queen mating evolved independently from single-mating ancestors, but that the mechanisms behind specific adaptions or ejaculate competition are unlikely to be the same (Boomsma 2009; Den Boer et al. 2010).

A significant (P < 0.001), but less pronounced expansion was observed for a family of peptidase M14 proteins (Fig. 3B), where A. echinatior has eight members, while the other ant species have four or five. All of these proteins belong to the CPA and CPB subfamily of metallocarboxypeptidases that require metal ions (often zinc) as cofactors and cleave amino acids from the carboxy end of polypeptides (Reznik and Fricker 2001; Rodriguez de la Vega et al. 2007). Some of these enzymes work as digestive enzymes with broad substrate specificity, while others activate or deactivate specific proteins by removing amino acids. D. melanogaster has 18 genes that cluster in the same family, of which 13 are primarily expressed in the larval or adult digestive system, while the remaining five have a broader expression, including high expression levels in the testes and spermatheca (Chintapalli et al. 2007, www.flyatlas.org; Tweedie et al. 2009, FlyBase.org). One of the A. echinatior proteins (EGI65848) has been found in the fecal fluid of the ants (M Schiøtt, unpubl.), which suggests a digestive role for these peptidases, either in the ant gut or in the fungus garden after defecation (Schiøtt et al. 2010).

Sex determination

In ants and other Hymenoptera, males develop from unfertilized eggs, whereas fertilized eggs develop into females, either workers or queens. In honeybees, sex is determined by the highly variable complementary sex determiner (csd) locus, which controls the alternative splicing of the homologous feminizer transcript, the actual effector of sex determination (Hasselmann et al. 2008). The presence of two different csd alleles therefore induces female development, whereas a single copy or two identical copies produce male phenotypes. Diploid males are occasionally observed in ants, particularly under inbreeding (Kronauer et al. 2007), suggesting that a mechanism similar to csd also applies in many ants. Consistent with this notion, all ant genomes sequenced so far have produced two homologs of the feminizer gene (Bonasio et al. 2010; Wurm et al. 2011). However, phylogenies suggest that the duplications in bees and ants are independent (Bonasio et al. 2010; Wurm et al. 2011), making it possible that the double feminizer homologs in ants and bees function differently.

In contrast to other ants, sequence searches revealed only a single homolog of feminizer in the A. echinatior genome (Supplemental Fig. S4). While it remains possible that another homolog exists, it would be unlikely to have been missed with >100× coverage, and we found no indications that the single locus results from a misassembly of two distinct genomic loci (Supplemental Fig. S4). The inferred genome sequence also completely matches the RNA-seq sequence as well as a previously obtained A. echinatior fem cDNA sequence from another ant colony (data not shown), making it unlikely that this genome region is not correctly assembled. The RNA-seq data furthermore indicate alternative splicing (Supplemental Fig. S4), increasing the likelihood that this gene is a de facto feminizer homolog.

The fact that the sex-determination system of A. echinatior can apparently work with a single feminizer homolog seems to shed some doubt on whether the independent duplications of feminizer in other ants are necessary for primary sex determination analogous to the way in which the csd locus functions in the honeybee. On the other hand, the high production of diploid male larvae in A. echinatior (Dijkstra and Boomsma 2007) could be an effect of having only one feminizer homolog. Workers of A. echinatior cull almost all diploid males and presumably do so early in larval development, so that the potentially high cost of diploid male production is almost always low in practice. Culling behavior may thus have evolved to compensate for an inefficient sex-determination system.

Neuropeptides

Neuropeptides are short peptides that interact with membrane-bound receptors, typically G protein-coupled receptors (Hauser et al. 2006, 2008, 2010) and steer important physiological processes such as development, reproduction, feeding, and behavior. In insects there are 46 known neuropeptide genes, and a recent study revealed that 20 of them (the core set) are consistently found in all insects with a sequenced genome (Hauser et al. 2010; Supplemental Table S14). The remaining 26 neuropeptide genes (the variable set) constitute family-, genus-, or species-specific neuropeptide gene profiles (Hauser et al. 2010; Supplemental Table S15). Because these neuropeptide gene profiles are likely to be related to variation in habitat, diet, or behavior across insect clades (Hauser et al. 2010), we expected to find differences both between the four ant genomes and between ants and other insects. However, we found that all four ant species share exactly the same neuropeptide gene profile (Supplemental Tables S16, S17). This profile is unique for ants and differs from that of other hymenopterans such as the honeybee and Nasonia wasps (Supplemental Table S18). These results indicate that the four ant species have a single common ancestor, consistent with other recent molecular evidence that all ants form a monophyletic clade (Brady et al. 2006; Moreau et al. 2006), and that their neuroendocrinology, despite their striking differences in habitat, feeding, and behavior, has a very similar basic set-up. This remarkable conservation across a family of insects that diverged >100 MYA suggests a link with the early evolution of eusociality in ants.

Another surprise, when carrying out this comparative endocrine genomics analysis, was the absence of the RYamide gene in all four ant genomes (Supplemental Table S16). The RYamide genes have only recently been discovered and were found to be present in all insects with a sequenced genome (the “core set”) (Hauser et al. 2010) and even in other arthropods, such as crustaceans and chelicerates (F Hauser, unpubl.). Their absence in ants is a unique joint feature and difficult to interpret at present. The biological action of insect RYamides is unknown, but mass spectrometry has shown that they are abundant in the terminal ganglion of mosquitoes (Hauser et al. 2010), which, in general, innervates the sexual organs in insects. The absence of the RYamide neuropeptides in ants might therefore be related to specific features of ant reproduction and possibly to the regulatory mechanisms that evolved together with the differentiation between reproductive and nonreproductive castes.

Concluding remarks

The genome sequence of A. echinatior shows that attine fungus-growing ants have great potential as model systems for studying symbiosis and reproductive conflict in the genomics era. The present study only allowed us to explore some of the significant changes that a history of 50 million years of obligate fungus farming can be expected to have induced. All of these will have to be elaborated by detailed experimental work to clarify the ways in which regulation of gene expression operates, a research agenda that will have to involve the total complexity of the symbiotic syndrome of fungus farming (e.g., Sen et al. 2009; Poulsen and Currie 2010; Schiøtt et al. 2010; Suen et al. 2010).

The attractiveness of this model system is that it is an ectosymbiosis, in which hosts and symbionts can be separated and maintained in independent lab cultures for considerable periods of time, and where cross-fostering and other manipulation experiments are feasible (Armitage et al. 2011). These opportunities have already been amply used, not only for A. echinatior (see the eight-point summary above), but also for a number of other attine ant model systems (e.g., Mueller et al. 2005; Schultz and Brady 2008; De Fine Licht et al. 2010). This kind of work can now be elaborated by gene expression studies that will be much more feasible with the availability of a reference genome.

Methods

Biological material and DNA/RNA extraction

A monogynous, queen-right colony of A. echinatior (Ae372) was collected in Gamboa, Panama in 2008, and maintained in the lab on a diet of bramble leaves and rice at 25°C and 60%–70% RH. Voucher specimens of this colony have been deposited at the Zoological Museum, Copenhagen. Since male ants are derived through arrhenotokous parthenogenesis, a single male contains one haploid genome, whereas a pool of males from a monogynous colony represents the diploid genome of that colony’s mother queen.

Short insert libraries (500 bp, 800 bp, and 2 kb) for Illumina sequencing were made from extracted DNA of a single male of colony Ae372 using the Qiagen DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit and the protocol provided by the manufacturer. Long insert libraries (5, 10, and 20 kb) for Illumina sequencing were made from the DNA of 40 males from colony Ae372. This DNA was extracted by grinding the ants in 5 mL of lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 400 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA at pH 8) and adding 200 μL of 20% SDS, 300 μL of 5 mg/mL proteinase K, and 10 μL of 100 mg/mL RNase A. After a 2-h incubation at 50°C, 5 mL of phenol/chloroform (1:1 pH 8) was added and the sample was mixed on a slowly rotating wheel for 15 min. The sample was subsequently centrifuged at 3000g for 10 min, after which the upper phase was transferred to a new tube and mixed with 5 mL of phenol/chloroform (1:1 pH 8). After mixing for 15 min on a slowly rotating wheel, the sample was centrifuged for another 10 min at 3000g, after which the upper phase was transferred to a new tube and mixed with 5 mL of chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (24:1). After another round of 15 min of mixing on a slowly rotating wheel, the sample was centrifuged again for 10 min at 3000g, after which the upper phase was transferred to a new tube and mixed with 0.5 volume isopropanol. The tube was then inverted 10–20 times before the precipitated DNA was collected with a glass hook made of a pasteur pipette. The DNA was dissolved in 1 mL of TE buffer overnight.

Total RNA was extracted from eggs, larvae, pupae, workers, males, and gynes from colony Ae372 by grinding the tissue in liquid nitrogen and purifying the RNA with a Qiagen RNeasy mini kit using Qiagen buffer RLC instead of buffer RLT. A pooled sample from all developmental stages was then generated to contain approximately equimolar amounts of RNA from each stage.

DNA sequencing

For Illumina DNA sequencing, five paired-end sequencing libraries were constructed with insert sizes of ∼500 bp, 800 bp, 2 kb, 5 kb, and 10 kb. For small insert libraries, 5 μg of DNA was sheared to fragments of 500–800 bp, end-repaired, A-tailed, and ligated to Illumina paired-end adapters (Illumina). The ligated fragments were size selected at 500 and 800 bp on agarose gels and amplified by LM-PCR to yield the corresponding short insert libraries. For long insert size mate-pair library construction, 20–40 μg of genomic DNA was sheared to the desired insert size using nebulization for 2 kb or HydroShear (Digilab) for 5 and 10 kb.

The DNA fragments were end-repaired using biotinylated nucleotide analogs (Illumina), size selected at 2, 5, and 10 kb. and circularized by intramolecular ligation. Circular DNA molecules were sheared with Adaptive Focused Acoustic (Covaris) to an average size of 500 bp. Biotinylated fragments were purified on magnetic beads (Invitrogen), end-repaired, A-tailed, and ligated to Illumina paired-end adapters, size-selected again, and purified by LM-PCR. After their construction, the libraries were sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 2000, with read lengths of 90–100 bp. Raw sequences were filtered for low quality, adapter sequence, paired-end read overlap, and PCR duplicates.

RNA sequencing

Total RNA was further purified using TRIzol (Invitrogen), and poly(A) RNA was isolated with oligo-dT-coupled beads from 20 μg of total RNA. First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed with random hexamers and Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). The second strand was synthesized with E. coli DNA PolI (Invitrogen). Double-stranded cDNA was purified with a Qiaquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and sheared with a nebulizer (Invitrogen) to 100–500-bp fragments. After end repair and addition of a 3′dA overhang, the cDNA was ligated to Illumina PE adapter oligo mix, and size selected to 200 ± 20-bp fragments by gel purification.

After PCR amplification the libraries were sequenced using Illumina HiSeq 2000 and the paired-end sequencing module. For smRNA-seq, we gel-purified 18–30 nt RNAs from the samples utilized for RNA-seq. Illumina 5′ and 3′ RNA adapters were sequentially ligated to the RNA fragments and the ligated products were size-selected on denaturing polyacrylamide gels. The adapter-linked RNA was reverse transcribed with small RNA RT primers and amplified with PCR using small RNA PCR primers 1 and 2 (Illumina). The libraries were sequenced with Illumina HiSeq 2000.

Genome assembly, filtering, and repeat identification

The genome was assembled using SOAPdenovo (Li et al. 2010) to first construct contigs based on the short insert libraries, then joining these to scaffolds using paired-end information, followed by local reassembly of unresolved gap regions. The sequencing coverage of the assembled genome sequence was evaluated by mapping the raw sequencing data back to the scaffolds using SOAPaligner (Li et al. 2009b), after which the coverage was calculated based on the k-mer distribution as described in Li et al. (2009a).

The RepeatMasker program (version 3.2.6) (Smit et al. 1996) was used to identify: (A) noninterspersed repeat sequences by using the “-noint” option, including Simple_repeat, Satellite, and Low_complexity repeats; (B) known transposable elements from the Repbase 15.02 Transposable Element (TE) library (Jurka et al. 2005); (C) additional high and medium copy number repeats (>10 copies) in the assembly, based on an ab initio repeat library constructed with RepeatScout (Price et al. 2005) with default parameters. In addition, we predicted tandem repeats using TRF (Benson 1999) with parameters set to “Match=2, Mismatch=7, Delta=7, PM=80, PI=10, Minscore=50, and MaxPeriod=12”.

The assembled genome was BLAST searched against the NCBI nt database, and contigs that aligned to bacterial sequences with >90% identity across >90% of their length were filtered out. All predicted gene models were BLAST searched against the NCBI nr database, and contigs/scaffolds were removed if >75% percent of their genes had highest similarity to bacterial sequences. The remaining assembled genome was realigned against the removed contigs/scaffolds, and contigs/scaffolds with >80% similarity across >80% of the sequence were removed. No sequences of fungal origin were identified. Bacterial scaffolds were reannotated using GeneMark.hmm-p (Lukashin and Borodovsky 1998) and removed for all subsequent analyses.

Transcript assembly and protein-coding gene annotation

RNA-seq reads were aligned to the genome using TopHat (Trapnell et al. 2009), (parameters “-p 4 -r 20–mate-std-dev 10 -I 10000–solexa1.3-quals”), which identifies exon–exon splice junctions. Then Cufflinks (Trapnell et al. 2010) was used to assemble transcripts with junction information (parameters “-m 20 -s 10 -I 10000”).

Sequence homology was assigned based on best TBLASTN hits (E-value <1×10−5) to gene sets from seven different species: C. floridanus (OGS v3.3), H. saltator (OGS v3.3), A. mellifera (Amel_4.0), N. vitripennis (Nvit_1.0) downloaded from NCBI, D. melanogaster, C. elegans, and Homo sapiens downloaded from Ensembl (release 56). This was followed by detailed protein–nucleotide alignment with Genewise (version 2.0) (Birney et al. 2004) to generate the gene structures.

Two de novo prediction programs, Augustus (Stanke et al. 2006) and SNAP (Korf 2004), were used to predict genes, with parameters trained on 500 randomly selected intact genes (full ORF found, including start and stop codon) from the homology-based predictions. The evidence derived from homology-based (seven sets for seven species), de novo (two sets for two programs), and expression (one set) were integrated by GLEAN (Elsik et al. 2007) to generate a consensus gene set.

In addition to the GLEAN-predicted genes, we expanded the gene set by adding gene models based on homology only: The seven homology-based gene-prediction sets were merged into a union set. For overlapping gene models, the longest was selected. These gene models were filtered by: (1) removing genes containing premature stop codons inside the coding region; (2) removing genes with more than two frameshifts; (3) removing genes with a Genewise score <80. For Genewise incomplete protein alignments, we extended the first exon upstream to find the start codon, and extended the last exon downstream to find the stop codon.

The gene models from the two de novo methods were similarly merged, and the longest model was chosen in cases of overlap. Gene models that did not pass the GLEAN criteria were still included if their expression level exceeded 5% of the whole genome level. All gene models were subsequently filtered for transposable elements (TEs) by running InterProSscan (Zdobnov and Apweiler 2001) (see also below) while removing genes matching TE-related protein domains. Manual checking of gene models was then performed using the Apollo Annotation editor (Lewis et al. 2002).

CEGMA validation, noncoding RNA annotation, and functional annotation of protein-coding genes

The CEGMA set of 458 core eukaryotic genes (CEGs) was used to predict genes in A. echinatior using the CEGMA pipeline (Parra et al. 2007). Predicted CEGMA genes were considered present in our gene set if they overlapped with existing gene models.

We predicted tRNAs with tRNAscan-SE (Lowe and Eddy 1997) using default eukaryote parameters, and identified rRNAs by aligning invertebrate rRNA sequences (downloaded from NCBI, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) to the assembly using BLASTN with an E-value of 1×10−5. The snRNA genes were predicted using the Infernal software (Nawrocki et al. 2009) against the Rfam database (Griffiths-Jones et al. 2005, release 9.1). To reduce the speed required for computation, a rough prefiltering was performed before running Infernal by BLASTN alignment of the assembly against the Rfam sequence database with an E-value cut-off of 1.

We predicted miRNAs based on both homology and expression. A set of known miRNAs was constructed by merging the previously identified miRNAs from H. saltator and C. floridanus (Bonasio et al. 2010) with animal miRNAs from miRBase (Griffiths-Jones et al. 2008, Release 16). A set of putative expressed miRNAs was obtained by extracting short reads (18–30 nt) from the RNA-seq data, filtered for low-quality sequence.

Known and putative miRNAs were aligned to the genome assembly using Bowtie (Langmead et al. 2009), allowing one mismatch. Hits that overlapped repeat, CDS, rRNA, tRNA, or snRNA annotation were ignored. MIREAP (Qibin and Jiang 2008) (default parameters) was then used to predict whether the hits were contained in miRNA-like secondary structures. When predicted miRNAs from the known and the expressed sets overlapped, the coordinates of the latter were used.

Protein domains and motifs were predicted for all genes by running InterProScan (Zdobnov and Apweiler 2001, v4.5) using known domains from Pfam, PRINTS, PROSITE, ProDom, and SMART (Release 27). Gene Ontology (GO) (Ashburner et al. 2000) IDs for each gene were obtained from the corresponding InterPro entry. KEGG function (Kanehisa and Goto 2000) was assigned by best BLASTP hit (parameter “-p blastp -b 10000 -v 10000 -F F -e 1e-5”) to all KEGG proteins (release 51).

Gene family assignment

Protein-coding genes from five eusocial (A. echinatior, S. invicta, C. floridanus, H. saltator, A. mellifera) and two other insects (N. vitripennis, D. melanogaster) were clustered into gene families based on conjoined BLASTP alignments using the Treefam methodology (Supplemental Fig. S3; Li et al. 2006). When more than one isoform was present from a given gene, we kept only the longest. After clustering, we performed multiple alignments of protein sequences for each gene family using MUSCLE (Edgar 2004) and reverse translated the protein alignments to CDS alignments.

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analyses

Fishers exact test was used to calculate the statistical significance of enrichment of GO categories. The P-values were adjusted for multiple testing (false discovery rate), using a cutoff of 0.05 for adjusted P-values. To remove redundancy in the GO enrichment results, only the lowest level was reported when GO categories with parent–child relationships contained the same gene sets.

Phylogenetic trees and gene family expansion/contraction

To generate the overall phylogeny of the six Hymenopteran genomes and D. melanogaster, fourfold degenerate (FFD) sites were extracted from MUSCLE alignments of 1995 single-copy gene families and merged into one alignment. The phylogeny was calculated using the PhyML (Guindon et al. 2009) implementation of Maximum-Likelihood, with the HKY85 substitution model. The root of the tree was determined by minimizing the height of the whole tree with TreeBeST (Ponting 2007).

To identify significantly expanded/contracted gene families, a linear time tree was estimated from the FFD alignment using UPGMA (Sneath and Sokal 1973) and used with CAFE (De Bie et al. 2006) to infer the significance of change in gene family size along each branch. This method takes into account the phylogenetic history, including rate and direction of change in gene family size.

The phylogenetic tree of the M16 Peptidase genes was constructed using Ruby/Bioruby (Aerts and Law 2009; Goto et al. 2010) scripts to organize the multiple alignment and tree construction. Predicted CDS sequences were first translated using transeq (Rice et al. 2000), and the resulting protein sequences were then aligned using MAFFT v6.717b (Katoh and Toh 2008) using the L-INS-i option for high accuracy. Subsequently, the protein sequences were reverse-translated with PAL2NAL v13 (Suyama et al. 2006) to produce a codon-level multiple alignment, while eliminating badly aligning segments by Gblocks 0.91b (Talavera and Castresana 2007). The codon alignment was then used as input to PhyML 3.0 (Guindon et al. 2009), run with the “-f e -d nt” parameters, a HKY85 model, and 1000 bootstraps. For the M14 Peptidase genes, protein sequences were aligned with MAFFT following the same procedure, and PhyML was run directly on the protein alignment with “-f e -d aa” parameters and 1000 bootstraps. Obtained trees were converted to PDF using FigTree (Rambaut 2006) and colors and labels were edited for clarity in Adobe Illustrator.

Feminizer gene searches

Search of six-frame translations of the A. echinatior genome was conducted with HMMER (http://hmmer.janelia.org/) v. 3.0, using several different HMM models made from alignments of: (1) Transformer/Feminizer (Tra/Fems) protein sequences from many insect species (separately for 3′ and 5′ ends), (2) Hymenopteran Tra/Fems, and (3) only ant Tra/Fems. These models consistently yielded only a single genomic match.

Neuropeptide annotation

Known invertebrate neuropeptide precursor and receptor sequences were used in TBLASTN and BLASTP homology searches against A. echinatior genomic scaffolds and annotated peptides (v.1.0) S. invicta (v.2.3), C. floridanus (v.3.3), and H. saltator (v.3.3). Gene structures and open reading frames were predicted using multiple web-based gene prediction programs, the CLC Main Workbench (www.clcbio.com), and by manual correction. Signal peptides were predicted using SIGNALP (Emanuelsson et al. 2007), and peptide processing was predicted using the ProP program (Duckert et al. 2004).

Data access

This Whole Genome Shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession no. AEVX00000000. The version described in this study is the first version, AEVX01000000. Raw sequence data is available under the accession no. ERP000666.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material – (.PDF, 334KB)

Acknowledgments

We thank the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama for making facilities available to work on fungus-growing ants, and the Autoridad Nacional del Ambiente (ANAM) of Panama for issuing collection and export permits. S.N., M.S., and J.J.B. were supported by the Danish National Research Foundation; F.H. and C.J.P.G. by the Danish Research Agency (FNU); and F.H., C.J.P.G., A.K., and S.N. were supported by different grants from the Novo Nordisk Foundation. Y.W. is supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation and an ERC grant to Laurent Keller. We thank Tom Gilbert, Laurent Keller, and Eske Willerslev for advice during the initial phases of this project; David R. Nash for helpful comments on the manuscript and for providing photographs of the ants; and Xuehong Meng, Qiulin Yao, Fengming Sun, Yong Liu, and Dongming Fang for assisting with the annotations. We thank Ioannis Xenarios for access to the Vital-IT (https://www.vital-it.ch) Center for high-performance computing of the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics, funded in part by the Integrated Computational Genomics Resources of the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics: RITA-CT-2006-026204.

Authors’ contributions: S.N., M.R., and A.K. performed the preliminary sequencing feasibility study. S.N., G.Z., M.S., A.K., J.W., and J.J.B. designed the research. S.N., G.Z., M.S., C.L., Y.W., F.Q., H.H., J.Z., L.J., H.P., F.H., and C.J.P.G. executed the research and analyzed the data. S.N., M.S., and J.J.B. wrote the paper (with input from F.H., C.L., G.Z., C.J.P.G., and Y.W.).

References

-

Aanen DK, Eggleton P, Rouland-Lefevre C, Guldberg-Froslev T, Rosendahl S, Boomsma JJ. 2002. The evolution of fungus-growing termites and their mutualistic fungal symbionts. Proc Natl Acad Sci 99: 14887–14892.

-

Aanen DK, de Fine Licht HH, Debets AJM, Kerstes NAG, Hoekstra RF, Boomsma JJ. 2009. High symbiont relatedness stabilizes mutualistic cooperation in fungus-growing termites. Science 326: 1103–1106.

-

Aerts J, Law A. 2009. An introduction to scripting in Ruby for biologists. BMC Bioinformatics 10: 221. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-221.

-

Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 25: 3389–3402.

-

Armitage S, Broch J, Fernández Marín H, Nash D, Boomsma J. 2011. Immune defence in leaf-cutting ants: a cross-fostering approach. Evolution 65: 1791–1799.

-

Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. 2000. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet 25: 25–29.

-

Baer B, Eubel H, Taylor NL, O’Toole N, Millar AH. 2009a. Insights into female sperm storage from the spermathecal fluid proteome of the honeybee Apis mellifera. Genome Biol 10: R67. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-6-r67.

-

Baer B, Heazlewood JL, Taylor NL, Eubel H, Millar AH. 2009b. The seminal fluid proteome of the honeybee Apis mellifera. Proteomics 9: 2085–2097.

-

Becker AB, Roth RA. 1992. An unusual active site identified in a family of zinc metalloendopeptidases. Proc Natl Acad Sci 89: 3835–3839.

-

Bekkevold, Boomsma JJ. 2000. Evolutionary transition to a semelparous life history in the socially parasitic ant Acromyrmex insinuator. J Evol Biol 13: 615–623.

-

Benson G. 1999. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 27: 573–580.

-

Birney E, Clamp M, Durbin R. 2004. GeneWise and Genomewise. Genome Res 14: 988–995.

-

Bonasio R, Zhang G, Ye C, Mutti NS, Fang X, Qin N, Donahue G, Yang P, Li Q, Li C, et al. 2010. Genomic comparison of the ants Camponotus floridanus and Harpegnathos saltator. Science 329: 1068–1071.

-

Boomsma JJ. 2009. Lifetime monogamy and the evolution of eusociality. Phil Trans R Soc B 364: 3191–3207.

-

Boomsma JJ. 2011. Farming writ small. Nature 469: 308–309.

-

Boomsma JJ, Kronauer DJC, Pedersen JS. 2009. Organization of insect societies: from genome to sociocomplexity (ed. Gadau J et al.), pp. 3–25. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

-

Bot AN, Rehner SA, Boomsma JJ. 2001. Partial incompatibility between ants and symbiotic fungi in two sympatric species of Acromyrmex leaf-cutting ants. Evolution 55: 1980–1991.

-

Brady SG, Schultz TR, Fisher BL, Ward PS. 2006. Evaluating alternative hypotheses for the early evolution and diversification of ants. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103: 18172–18177.

-

Brock DA, Douglas TE, Queller DC, Strassmann JE. 2011. Primitive agriculture in a social amoeba. Nature 469: 393–396.

-

Chesneau V, Pierotti AR, Barré N, Créminon C, Tougard C, Cohen P. 1994. Isolation and characterization of a dibasic selective metalloendopeptidase from rat testes that cleaves at the amino terminus of arginine residues. J Biol Chem 269: 2056–2061.

-

Chintapalli VR, Wang J, Dow JAT. 2007. Using FlyAtlas to identify better Drosophila melanogaster models of human disease. Nat Genet 39: 715–720.

-

De Bie T, Cristianini N, Demuth JP, Hahn MW. 2006. CAFE: a computational tool for the study of gene family evolution. Bioinformatics 22: 1269–1271.

-

De Fine Licht HH, Schiøtt M, Mueller UG, Boomsma JJ. 2010. Evolutionary transitions in enzyme activity of ant fungus gardens. Evolution 64: 2055–2069.

-

Den Boer SPA, Baer B, Boomsma JJ. 2010. Seminal fluid mediates ejaculate competition in social insects. Science 327: 1506–1509.

-

Diamond J. 2002. Evolution, consequences and future of plant and animal domestication. Nature 418: 700–707.

-

Dijkstra MB, Boomsma JJ. 2007. The economy of worker reproduction in Acromyrmex leafcutter ants. Anim Behav 74: 519–529.

-

Duckert P, Brunak S, Blom N. 2004. Prediction of proprotein convertase cleavage sites. Protein Eng Des Sel 17: 107–112.

-

Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32: 1792–1797.

-

Elsik CG, Mackey AJ, Reese JT, Milshina NV, Roos DS, Weinstock GM. 2007. Creating a honey bee consensus gene set. Genome Biol 8: R13. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-1-r13.

-

Emanuelsson O, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. 2007. Locating proteins in the cell using TargetP, SignalP and related tools. Nat Protoc 2: 953–971.

-

Farrell BD, Sequeira AS, O’Meara BC, Normark BB, Chung JH, Jordal BH. 2001. The evolution of agriculture in beetles (Curculionidae: Scolytinae and Platypodinae). Evolution 55: 2011–2027.

-

Feldhaar H, Straka J, Krischke M, Berthold K, Stoll S, Mueller MJ, Gross R. 2007. Nutritional upgrading for omnivorous carpenter ants by the endosymbiont Blochmannia. BMC Biol 5: 48. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-5-48.

-

Fumagalli P, Accarino M, Egeo A, Scartezzini P, Rappazzo G, Pizzuti A, Avvantaggiato V, Simeone A, Arrigo G, Zuffardi O, et al. 1998. Human NRD convertase: a highly conserved metalloendopeptidase expressed at specific sites during development and in adult tissues. Genomics 47: 238–245.

-

Goto N, Prins P, Nakao M, Bonnal R, Aerts J, Katayama T. 2010. BioRuby: Bioinformatics software for the Ruby programming language. Bioinformatics 26: 2617–2619.

-

Graf J, Ruby EG. 1998. Host-derived amino acids support the proliferation of symbiotic bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci 95: 1818–1822.

-

Griffiths-Jones S, Moxon S, Marshall M, Khanna A, Eddy SR, Bateman A. 2005. Rfam: annotating non-coding RNAs in complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 33: D121–D124.

-

Griffiths-Jones S, Saini HK, van Dongen S, Enright AJ. 2008. miRBase: tools for microRNA genomics. Nucl Acids Res 36: D154–D158.

-

Guindon S, Delsuc F, Dufayard JF, Gascuel O. 2009. Estimating maximum likelihood phylogenies with PhyML. Methods Mol Biol 537: 113–137.

-

Hasselmann M, Gempe T, Schiøtt M, Nunes-Silva CG, Otte M, Beye M. 2008. Evidence for the evolutionary nascence of a novel sex determination pathway in honeybees. Nature 454: 519–522.

-

Hata H, Watanabe K, Kato M. 2010. Geographic variation in the damselfish-red alga cultivation mutualism in the Indo-West Pacific. BMC Evol Biol 10: 185. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-19-185.

-

Hauser F, Cazzamali G, Williamson M, Blenau W, Grimmelikhuijzen CJP. 2006. A review of neurohormone GPCRs present in the fruitfly Drosophila melanogaster and the honey bee Apis mellifera. Prog Neurobiol 80: 1–19.

-

Hauser F, Cazzamali G, Williamson M, Park Y, Li B, Tanaka Y, Predel R, Neupert S, Schachtner J, Verleyen P, et al. 2008. A genome-wide inventory of neurohormone GPCRs in the red flour beetle Tribolium castaneum. Front Neuroendocrinol 29: 142–165.

-

Hauser F, Neupert S, Williamson M, Predel R, Tanaka Y, Grimmelikhuijzen CJP. 2010. Genomics and peptidomics of neuropeptides and protein hormones present in the parasitic wasp Nasonia vitripennis. J Proteome Res 9: 5296–5310.

-

Honeybee Genome Sequencing Consortium. 2006. Insights into social insects from the genome of the honeybee Apis mellifera. Nature 443: 931–949.

-

Hospital V, Prat A, Joulie C, Chérif D, Day R, Cohen P. 1997. Human and rat testis express two mRNA species encoding variants of NRD convertase, a metalloendopeptidase of the insulinase family. Biochem J 327: 773–779.

-

Hughes WOH, Boomsma JJ. 2004. Genetic diversity and disease resistance in leaf-cutting ant societies. Evolution 58: 1251–1260.

-

Hughes WOH, Boomsma JJ. 2006. Does genetic diversity hinder parasite evolution in social insect colonies? J Evol Biol 19: 132–143.

-

Hughes WOH, Boomsma JJ. 2008. Genetic royal cheats in leaf-cutting ant societies. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105: 5150–5153.

-

Hughes WOH, Sumner S, Van Borm S, Boomsma JJ. 2003. Worker caste polymorphism has a genetic basis in Acromyrmex leaf-cutting ants. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100: 9394–9397.

-

Ivens ABF, Nash DR, Poulsen M, Boomsma JJ. 2009. Caste-specific symbiont policing by workers of Acromyrmex fungus-growing ants. Behav Ecol 20: 378–384.

-

Jurka J, Kapitonov VV, Pavlicek A, Klonowski P, Kohany O, Walichiewicz J. 2005. Repbase Update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenet Genome Res 110: 462–467.

-

Kanehisa M, Goto S. 2000. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 28: 27–30.

-

Katoh K, Toh H. 2008. Recent developments in the MAFFT multiple sequence alignment program. Brief Bioinform 9: 286–298.

-

Klasson L, Andersson SG. 2004. Evolution of minimal-gene-sets in host-dependent bacteria. Trends Microbiol 12: 37–43.

-

Korf I. 2004. Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinformatics 5: 59. doi: 10.1186/147-2105-5-59.

-

Kronauer DJC, Johnson RA, Boomsma JJ. 2007. The evolution of multiple mating in army ants. Evolution 61: 413–422.

-

Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg S. 2009. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol 10: R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25.

-

Lewis SE, Searle SM, Harris N, Gibson M, Lyer V, Richter J, Wiel C, Bayraktaroglir L, Birney E, Crosby MA, et al. 2002. Apollo: a sequence annotation editor. Genome Biol 3: RESEARCH0082. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-12-research0082.

-

Li H, Coghlan A, Ruan J, Coin LJ, Hériché J-K, Osmotherly L, Li R, Liu T, Zhang Z, Bolund L, et al. 2006. TreeFam: a curated database of phylogenetic trees of animal gene families. Nucleic Acids Res 34: D572–D580.

-

Li R, Fan W, Tian G, Zhu H, He L, Cai J, Huang Q, Cai Q, Li B, Bai Y, et al. 2009a. The sequence and de novo assembly of the giant panda genome. Nature 463: 311–317.

-

Li R, Yu C, Li Y, Lam T-W, Yiu S-M, Kristiansen K, Wang J. 2009b. SOAP2: an improved ultrafast tool for short read alignment. Bioinformatics 25: 1966–1967.

-

Li R, Zhu H, Ruan J, Qian W, Fang X, Shi Z, Li Y, Li S, Shan G, Kristiansen K, et al. 2010. De novo assembly of human genomes with massively parallel short read sequencing. Genome Res 20: 265–272.

-

Lowe TM, Eddy SR. 1997. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 25: 955–964.

-

Lukashin A, Borodovsky M. 1998. GeneMark.hmm: new solutions for gene finding. Nucleic Acids Res 26: 1107–1115.

-

Mikheyev AS, Vo T, Mueller UG. 2008. Phylogeography of post-Pleistocene population expansion in a fungus-gardening ant and its microbial mutualists. Mol Ecol 17: 4480–4488.

-

Moreau CS, Bell CD, Vila R, Archibald SB, Pierce NE. 2006. Phylogeny of the ants: diversification in the age of angiosperms. Science 312: 101–104.

-

Mueller U, Gerardo N, Aanen D, Six D, Schultz T. 2005. The evolution of agriculture in insects. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 36: 563–595.

-

Nawrocki EP, Kolbe DL, Eddy SR. 2009. Infernal 1.0: inference of RNA alignments. Bioinformatics 25: 1335–1337.

-

Parra G, Bradnam K, Korf I. 2007. CEGMA: a pipeline to accurately annotate core genes in eukaryotic genomes. Bioinformatics 23: 1061–1067.

-

Ponting C. 2007. TreeBeST: Tree building guided by Species Tree. http://treesoft.sourceforge.net/treebest.shtml.

-

Poulsen M, Boomsma JJ. 2005. Mutualistic fungi control crop diversity in fungus-growing ants. Science 307: 741–744.

-

Poulsen M, Currie CR. 2010. Symbiont interactions in a tripartite mutualism: exploring the presence and impact of antagonism between two fungus-growing ant mutualists. PLoS ONE 5: e8748. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008748.

-

Price AL, Jones NC, Pevzner PA. 2005. De novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics 21: i351–i358. Abstract

-

Qibin L, Jiang W. 2008. MIREAP: MicroRNA Discovery By Deep Sequencing. http://sourceforge.net/projects/mireap/.

-

Rambaut A. 2006. FigTree. http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/.

-

Reznik SE, Fricker LD. 2001. Carboxypeptidases from A to Z: implications in embryonic development and Wnt binding. Cell Mol Life Sci 58: 1790–1804.

-

Rice P, Longden I, Bleasby A. 2000. EMBOSS: The European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite. Trends Genet 16: 276–277.

-

Rodriguez de la Vega M, Sevilla RG, Hermoso A, Lorenzo J, Tanco S, Diez A, Fricker LD, Bautista JM, Avilés FX. 2007. Nna1-like proteins are active metallocarboxypeptidases of a new and diverse M14 subfamily. FASEB J 21: 851–865.

-

Schiøtt M, De Fine Licht HH, Lange L, Boomsma JJ. 2008. Towards a molecular understanding of symbiont function: identification of a fungal gene for the degradation of xylan in the fungus gardens of leaf-cutting ants. BMC Microbiol 8: 40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-40.

-

Schiøtt M, Rogowska-Wrzesinska A, Roepstorff P, Boomsma JJ. 2010. Leaf-cutting ant fungi produce cell wall degrading pectinase complexes reminiscent of phytopathogenic fungi. BMC Biol 8: 156. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8156.

-

Schultz TR, Brady SG. 2008. Major evolutionary transitions in ant agriculture. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105: 5435–5440.

-

Schultz TR, Bekkevold D, Boomsma JJ. 1998. Acromyrmex insinuator new species: an incipient social parasite of fungus-growing ants. Insectes Soc 45: 457–471.

-

Schultz TR, Mueller UG, Currie CR, Rehner SA. 2005. Reciprocal illumination: A comparison of agriculture in humans and in fungus-growing ants. In Insect-fungal associations: Ecology and evolution (ed. Vega FE, Blackwell M ). Oxford University Press, New York.

-

Sen R, Ishak HD, Estrada D, Dowd SE, Hong E, Mueller UG. 2009. Generalized antifungal activity and 454-screening of Pseudonocardia and Amycolatopsis bacteria in nests of fungus-growing ants. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 17805–17810.

-

Silliman BR, Newell SY. 2003. Fungal farming in a snail. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100: 15643–15648.

-

Sirviö A, Gadau J, Rueppell O, Lamatsch D, Boomsma JJ, Pamilo P, Page RE Jr.. 2006. High recombination frequency creates genotypic diversity in colonies of the leaf-cutting ant Acromyrmex echinatior. J Evol Biol 19: 1475–1485.

-

Smit AFA, Hubley R, Green P. 1996. RepeatMasker Open-3.0. http://repeatmasker.org.

-

Sneath PHA, Sokal RR. 1973. Numerical taxonomy: The principles and practice of numerical classification. W.H. Freeman, San Francisco, CA.

-

Stanke M, Keller O, Gunduz I, Hayes A, Waack S, Morgenstern B. 2006. AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res 34: W435–W439.

-

Suen G, Scott JJ, Aylward FO, Adams SM, Tringe SG, Pinto-Tomás AA, Foster CE, Pauly M, Weimer PJ, Barry KW, et al. 2010. An insect herbivore microbiome with high plant biomass-degrading capacity. PLoS Genet 6: e1001129. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001129.

-

Sumner S, Hughes WOH, Boomsma JJ. 2003a. Evidence for differential selection and potential adaptive evolution in the worker caste of an inquiline social parasite. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 54: 256–263.

-

Sumner S, Nash DR, Boomsma JJ. 2003b. The adaptive significance of inquiline parasite workers. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 270: 1315–1322.

-

Sumner S, Hughes WOH, Pedersen JS, Boomsma JJ. 2004. Ant parasite queens revert to mating singly. Nature 428: 35–36.

-

Suyama M, Torrents D, Bork P. 2006. PAL2NAL: robust conversion of protein sequence alignments into the corresponding codon alignments. Nucleic Acids Res 34: W609–W612.

-

Talavera G, Castresana J. 2007. Improvement of phylogenies after removing divergent and ambiguously aligned blocks from protein sequence alignments. Syst Biol 56: 564–577.

-

Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL. 2009. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics 25: 1105–1111.

-

Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, Salzberg SL, Wold BJ, Pachter L. 2010. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol 28: 511–515.

-

Tweedie S, Ashburner M, Falls K, Leyland P, McQuilton P, Marygold S, Millburn G, Osumi-Sutherland D, Schroeder A, Seal R, et al. 2009. FlyBase: enhancing Drosophila Gene Ontology annotations. Nucleic Acids Res 37: D555–D559.

-

Van Borm S, Wenseleers T, Billen J, Boomsma JJ. 2003. Cloning and sequencing of wsp encoding gene fragments reveals a diversity of co-infecting Wolbachia strains in Acromyrmex leafcutter ants. Mol Phylogenet Evol 26: 102–109.

-

Villesen P, Murakami T, Schultz TR, Boomsma JJ. 2002. Identifying the transition between single and multiple mating of queens in fungus-growing ants. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 269: 1541–1548.

-

Werren JH, Richards S, Desjardins CA, Niehuis O, Gadau J, Colbourne JK, Group TNGW. 2010. Functional and evolutionary insights from the genomes of three parasitoid Nasonia species. Science 327: 343–348.

-

Wurm Y, Wang J, Riba-Grognuz O, Corona M, Nygaard S, Hunt BG, Ingram KK, Falquet L, Nipitwattanaphon M, Gotzek D, et al. 2011. The genome of the fire ant Solenopsis invicta. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108: 5679–5684.

-

Zdobnov EM, Apweiler R. 2001. InterProScan - an integration platform for the signature-recognition methods in InterPro. Bioinformatics 17: 847–848.

Footnotes

Article published online before print. Article, supplemental material, and publication date are at https://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.121392.111.

Received February 3, 2011.

Accepted May 25, 2011.

Copyright © 2011 by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press