Ants, Bees, Genomes & Evolution @ Queen Mary University London

Published: 12 October 2016

Impact of controlled neonicotinoid exposure on bumblebees in a realistic field setting

Andres N. Arce, Thomas I. David, Emma L. Randall, Ana Ramos Rodrigues, Thomas J. Colgan, Yannick Wurm, Richard J. Gill

Molecular Ecology, 26:2864-79

Summary

- Pesticide exposure has been implicated as a contributor to insect pollinator declines. In social bees, which are crucial pollination service providers, the effect of low-level chronic exposure is typically non-lethal leading researchers to consider whether exposure induces sublethal effects on behaviour and whether such impairment can affect colony development.

- Studies under laboratory conditions can control levels of pesticide exposure and elucidate causative effects, but are often criticized for being unrealistic. In contrast, field studies can monitor bee responses under a more realistic pesticide exposure landscape; yet typically such findings are limited to correlative results and can lack true controls or sufficient replication. We attempt to bridge this gap by exposing bumblebees to known amounts of pesticides when colonies are placed in the field.

- Using 20 bumblebee colonies, we assess the consequences of exposure to the neonicotinoid clothianidin, provided in sucrose at a concentration of five parts per billion, over 5 weeks. We monitored foraging patterns and pollen collecting performance from 3282 bouts using either a non-invasive photographic assessment, or by extracting the pollen from returning foragers. We also conducted a full colony census at the beginning and end of the experiment.

- In contrast to studies on other neonicotinoids, showing clear impairment to foraging behaviours, we detected only subtle changes to patterns of foraging activity and pollen foraging during the course of the experiment. However, our colony census measures showed a more pronounced effect of exposure, with fewer adult workers and sexuals in treated colonies after 5 weeks.

- Synthesis and applications. Pesticide-induced impairments on colony development and foraging could impact on the pollination service that bees provide. Therefore, our findings, that bees show subtle changes in foraging behaviour and reductions in colony size after exposure to a common pesticide, have important implications and help to inform the debate over whether the benefits of systemic pesticide application to flowering crops outweigh the costs. We propose that our methodology is an important advance to previous semi-field methods and should be considered when considering improvements to current ecotoxicological guidelines for pesticide risk assessment.

Introduction

Vast areas of crop monocultures have become common practice in modern agriculture, with a heavy reliance on chemical insecticides to prevent crop damage from insect pests. However, while insecticide application provides the obvious benefits of controlling insect pest populations, we understand less about the costs associated with inadvertent exposure to non-target organisms (Desneux, Decourtye & Delpuech 2007; Goulson 2013). Many non-target insect species provide an important pollinator service, with ca. 75% of agricultural crop species being (to some degree) dependent on pollination which represents an estimated global economic value of over €150 billion per annum (Klein et al. 2007; Gallai et al. 2009), as well as maintaining healthy wild-flower populations (Ollerton, Winfree & Tarrant 2011). Hence, it is important we understand the potential risks posed to insect pollinators by stressors, such as insecticide exposure (Gill et al. 2016). Indeed, concern over insect pollinator declines is growing (Kremen & Ricketts 2000; Biesmeijer et al. 2006; Brown & Paxton 2009; Cameron et al. 2011; Burkle, Marlin & Knight 2013) and insecticides have been implicated as a contributing factor (Desneux, Decourtye & Delpuech 2007; Vanbergen & Initiative 2013; Goulson 2015).

Bees are considered to be the major contributor to insect pollination (Greenleaf & Kremen 2006; Klein et al. 2007; Winfree et al. 2008; Potts et al. 2010), and there is increasing evidence to support that insecticide exposure can lead to sublethal behavioural effects (Desneux, Decourtye & Delpuech 2007; Gill, Ramos-Rodriguez & Raine 2012; Gill & Raine 2014; Lundin et al. 2015), potentially increasing susceptibility to other stressors such as pathogens (Alaux et al. 2010; Fauser-Misslin et al. 2014). Furthermore, in social bees, pesticide-induced impairments to colony functions, such as foraging, could accumulate and eventually lead to a significant decrease in colony size or even collapse (Bryden et al. 2013; Perry et al. 2015). Yet we still have a limited understanding of whether, and how, exposure to pesticides in semi-field or field environments might impair foraging behaviour (Gill, Ramos-Rodriguez & Raine 2012; Henry et al. 2012; Schneider et al. 2012; Fischer et al. 2014; Gill & Raine 2014; Stanley et al. 2016).

To date, however, there has been criticism surrounding many pesticide exposure studies highlighting that most do not represent true field scenarios (i.e. based in artificial laboratory or semi-field conditions), and may have used unrealistically high concentrations and/or doses (Raine & Gill 2015). Moreover, the majority of studies on bees have often concentrated on effects of acute exposure, yet we understand relatively little about chronic effects (Gill & Raine 2014; Stanley et al. 2016), the potential impacts on colony fitness when considering social bees, and whether the pollination services are altered when bees are sublethally impaired (Gill, Ramos-Rodriguez & Raine 2012; Whitehorn et al. 2012; Bryden et al. 2013; Perry et al. 2015; Rundlöf et al. 2015; Stanley et al. 2015).

We conducted an experiment that bridged the gap between laboratory and field studies. We placed bumblebee colonies Bombus terrestris audax (Harris, 1776), in a field setting, and exposed them to a commonly used neonicotinoid pesticide, clothianidin, at concentrations approximating field realistic levels (Table S1, Supporting Information). Globally, neonicotinoids are a widely used class of pesticide that are, due to their systemic properties, readily taken up by treated plants to provide protection across all tissues for an extended period of time (Elbert et al. 2008). However, residues are found in the nectar and pollen of treated/contaminated flowering plants resulting in a direct route of exposure to foraging insect pollinators such as bees (Rortais et al. 2005). In recent years, clothianidin has been one of the most heavily used neonicotinoids (Goulson 2013), and calls for evidence on the acute and chronic risks that clothianidin, as well as other neonicotinoids, pose to insect pollinators have been issued (EFSA 2013a). This study undertook careful observations of B. t. audax colonies providing detailed insights to the foraging behaviour of 20 colonies across 5 weeks when provisioned with sucrose solution spiked with clothianidin at five parts per billion (ppb), or a sucrose control solution, allowing us to address the potential chronic effects of exposure on: (i) foraging activity (rate of returning forager bees), (ii) pollen foraging performance; (iii) any effect of wind speed and temperature on foraging patterns; and (iv) a comparison of endpoint measures including colony brood weight and the production of eggs, larvae, pupae and adults.

Materials and methods

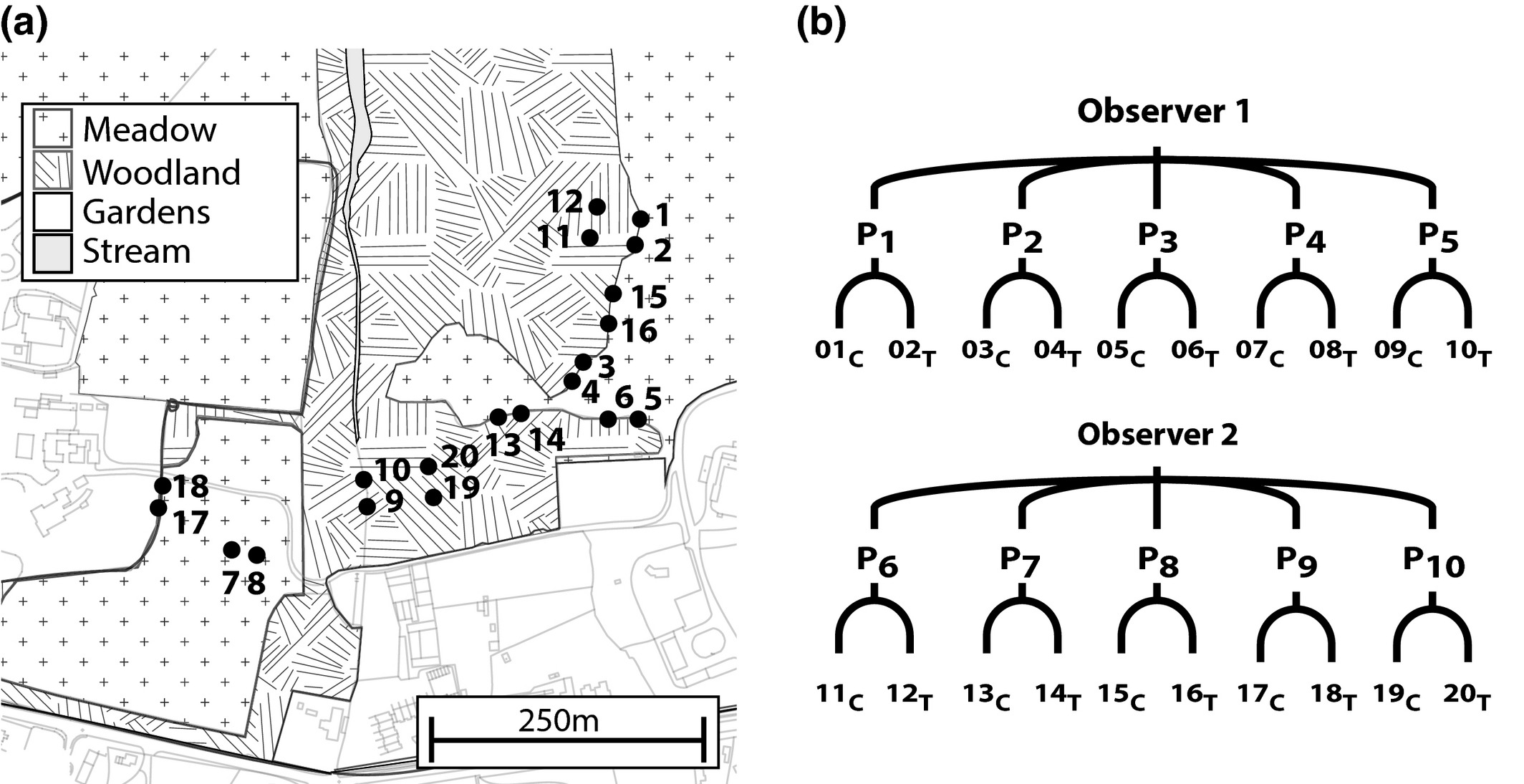

Field Colonies, Experimental Feeding Regime and Treatment

Each B. t. audax colony [mean (±SEM) workers per colony = 44·4 ± 1·67; range = 35–58] was placed inside a wooden nest box which was then placed within a 110-L plastic container for protection from weathering and predation. The containers were set in the grounds of Silwood Park campus (110 ha site of non-agricultural parkland on 6 June 2013, see Figs 1a and S1, and electronic supplementary material for description of nesting boxes and land type). Colonies were assigned to ten pairs using a split block design to experimentally control for differences in initial colony size (Fig. 1b), and each pair was randomly assigned to either a control or treatment group (Table S2). We found no significant difference in colony size between the control and treatment group in either worker or pupae number (GLM: workers: Z = 0·738, P = 0·46; pupae: T = 1·221, P = 0·238). Colonies within a pair were located 8–10 m from each other, and pairs were placed a minimum of 25 m apart.

Figure 1

(a) Map showing the spatial locations of the 20 colonies in Silwood Park, those colonies placed inside woodland areas were sited within clearings; (b) a schematic of the split block design showing each observer, pairings (Pn) and individual colony identification (nC = control, nT = treatment).

Colonies were provided with sucrose solution three times per week, with the calculated volume provided deemed to be half that which colonies would typically consume over the course of the experiment (see electronic supplementary information and Table S3 for details), but we did not provide any pollen. All control colonies (n = 10) were fed untreated 40% v/v sucrose/water solution. Treated colonies (n = 10) were fed sucrose solution containing a five ppb concentration of clothianidin which approximates a field realistic concentration (range found in flowering agricultural crops: <1·0–14 ppb in nectar; see Table S1). Colonies remained in the field for 5 weeks (35 days) and were then frozen. A colony census was then conducted by recording colony structure weight (wax, pollen stores and nectar pots) and the number of eggs, larvae, pupae, workers and sexuals present. As B. t. audax is a native UK subspecies, we did not fit the colonies with queen excluders, but this meant we were unable to prevent the dispersal of gynes from the colonies; therefore, the number of gynes in the colony represents a snapshot of the colony at the end of the experiment.

Colony Observations

Observations started 3 days after the first sucrose provision, with each colony observed one hour per day for 2 days per week (total = 200 h over all 20 colonies for the 5 weeks; see Table S4). Prior to the start of the experiment, five pairs were assigned to observer 1 and the remaining five pairs to observer 2 (Fig. 1b). Both the order in which the colony pairs were observed each day and the order each individual colony within a pair was observed were randomised, and there was no significant difference in colony size between observer 1 and 2 in either worker or pupae number (GLM: workers: Z = 0·872, P = 0·383; pupae: T = −0·234, P = 0·817).

Observers were positioned beside the plastic box at a distance of 0·5–1 m to view the transparent entrance tube. Any worker returning to the colony was assumed to be a forager, and observers collected common measurements that included: (i) counting the number of returning foragers (forager ‘activity’); (ii) recording whether foragers were carrying pollen; and (iii) taking the mean of three temperature (°C) and wind speed (m s−1) readings outside (1 m) of the plastic box. In addition, each observer carried out measurements exclusive to themselves:

Observer 1 – pollen removal

When a forager returned with pollen, a plastic ‘trap-door’ was used to prevent the bee from entering the colony. The bee was then held with forceps, and the pollen load from one leg was removed with a spatula and stored at −20 °C. We only took pollen from one corbicula as removal from both may affect future forager motivation (Raine & Chittka 2007). As pollen is typically gathered into each corbicula evenly (Winston 1991), we assumed that the weight of the pollen load mass was half of the total collected pollen. At the end of the observation, each pollen load was weighed (accuracy: ±0·1 mg).

Observer 2 – photographic method

A standardized photograph was taken of each returning forager [Nikon D3300 SLR (Tokyo, Japan) fitted with a remote shutter release and 18–55 mm f/3·5–5·6 A-FP Non VR Lens] with the camera consistently placed 200 mm from the entrance tube with a 55 mm focal length. We then calculated the 2D-surface area (Fig. S2) of the pollen load using the software package Image J (Rassband 1997–2015) relative to a 10-mm scale bar drawn on the side of the entrance tube.

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using r version 3.0.1 (R Development Core Team 2014), with mixed effects models using the lme4 (Bates et al. 2015) package and Gaussian, Binomial or Poisson distributions were used where appropriate (see model output Tables S5–S7). For foraging data, the spatial structure of paired colonies and observation regime of the experiment was modelled by nesting the variable Colony within Pair within Observer as random effects, while we included a random slope by observation Day to account for temporal pseudoreplication. Fixed factors included Treatment, Time (either hour of day, or day in the experiment) and Treatment × Time interaction. We initially fitted each model to include Temperature and Wind Speed as covariates, but these were only retained when their removal significantly decreased the fit of the model, determined by a significant likelihood ratio test. All models analysing colony census data included Treatment as a fixed effect and Pair nested in Observer as random effects.

Results

Over five weeks we recorded 3282 observations of foragers returning to the 20 colonies [mean (±SEM) bouts per colony = 164·10 ± 10·60], with 54% carrying pollen loads (pollen removal method: 904/1664; photographic method: 2: 950/1618). Bees from control and treatment colonies consumed similar amounts of sucrose from the feeders [mean (±SEM) volume consumed per colony: Control = 547·5 ± 51·0, vs. Treatment = 563·6 ± 42·7 mL; paired t-test: t = −0·32, d.f. = 9, P = 0·757; Table S3].

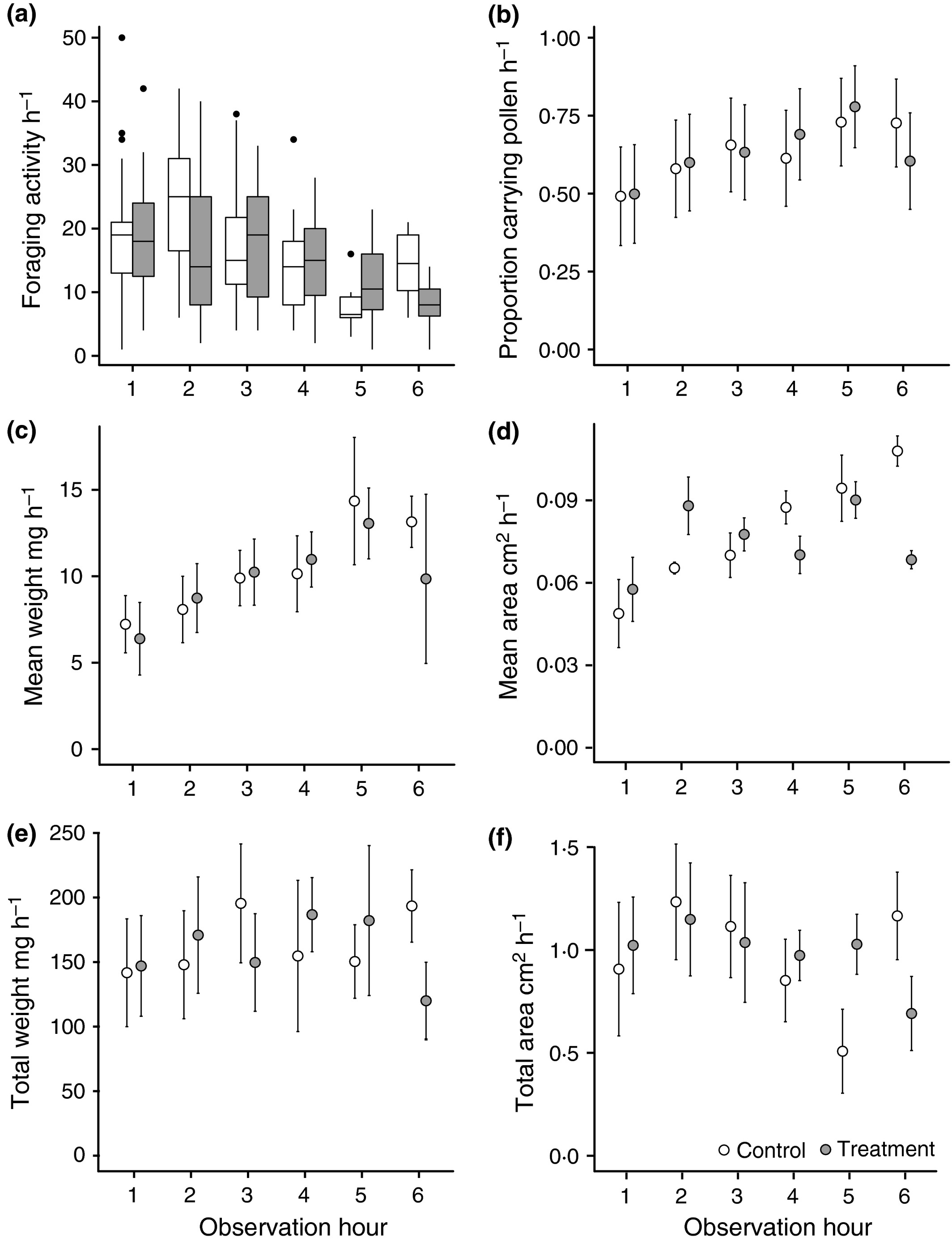

Foraging by Time of Day

Average foraging activity was higher in control relative to treated colonies as shown by the significant main effect of treatment and a lack of a significant interaction between treatment and observation hour (GLMER: ‘Treatment’ Z = −2·542, P = 0·011, ‘Treatment’ × ‘Time’ Z = 0·510, P = 0·610; Fig. 2a, Table S5a); however, foraging activity in both groups declined as the day progressed (Z = −6·346, P < 0·001). In contrast, the proportion of foragers carrying pollen increased as the day progressed (GLMER: Z = 4·508, P < 0·001) with both treatment and control colonies responding similarly (‘Treatment’ and ‘Treatment × Time’ interaction Z ≤ 1·501, P ≥ 0·33; Fig. 2b, Table S5b). The average pollen load weight increased as the day progressed (LMER: χ2 = 11·523, P = 0·003, Fig. 2c) with no difference between foragers from control and treated colonies (χ2 ≤ 2·055, P ≥ 0·357; Fig. 2c and Table S5c). However, the mean area of the pollen load (calculated from the photo images) from control colonies was initially smaller (LMER χ2 = 18·527, P < 0·001) and increased as the day progressed (χ2 = 11·72, P = 0·003), whereas they remained relatively constant on foragers from treated colonies (χ2 = 11·956, P < 0·001; Fig. 2d; Table S5d). Despite the minor effects of treatment detected by the photographic method, these did not translate into significant differences in either total weight or area of pollen brought back as there was no significant main or interactive effect with treatment (LMER: χ2 < 3·61, P > 0·165; Fig. 2e,f; Table S5e,f).

Figure 2

Trends in foraging behaviour throughout the day plotted from the raw data gathered across the 5 weeks: (a) box plots show foraging activity h-1 of observation; (b) mean proportion of foragers observed carrying pollen h-1; (c) mean weight of pollen brought back h-1; (d) total weight of pollen brought back h-1; (e) mean weight of pollen brought back h-1; (f) total area of pollen brought back h-1. Plots (a, b) relate to data collected by both observers, while (c–f) relates to data from each individual observer. Box plot central line indicates median value, box area represents the lower and upper quartiles, and whiskers indicate 95% CI. Error bars in (b–f) represent s.e.m. Observation hour 1–6 depicts the following start times, respectively: 08:30; 09:45; 11:00; 12:15; 14:00; 15:15.

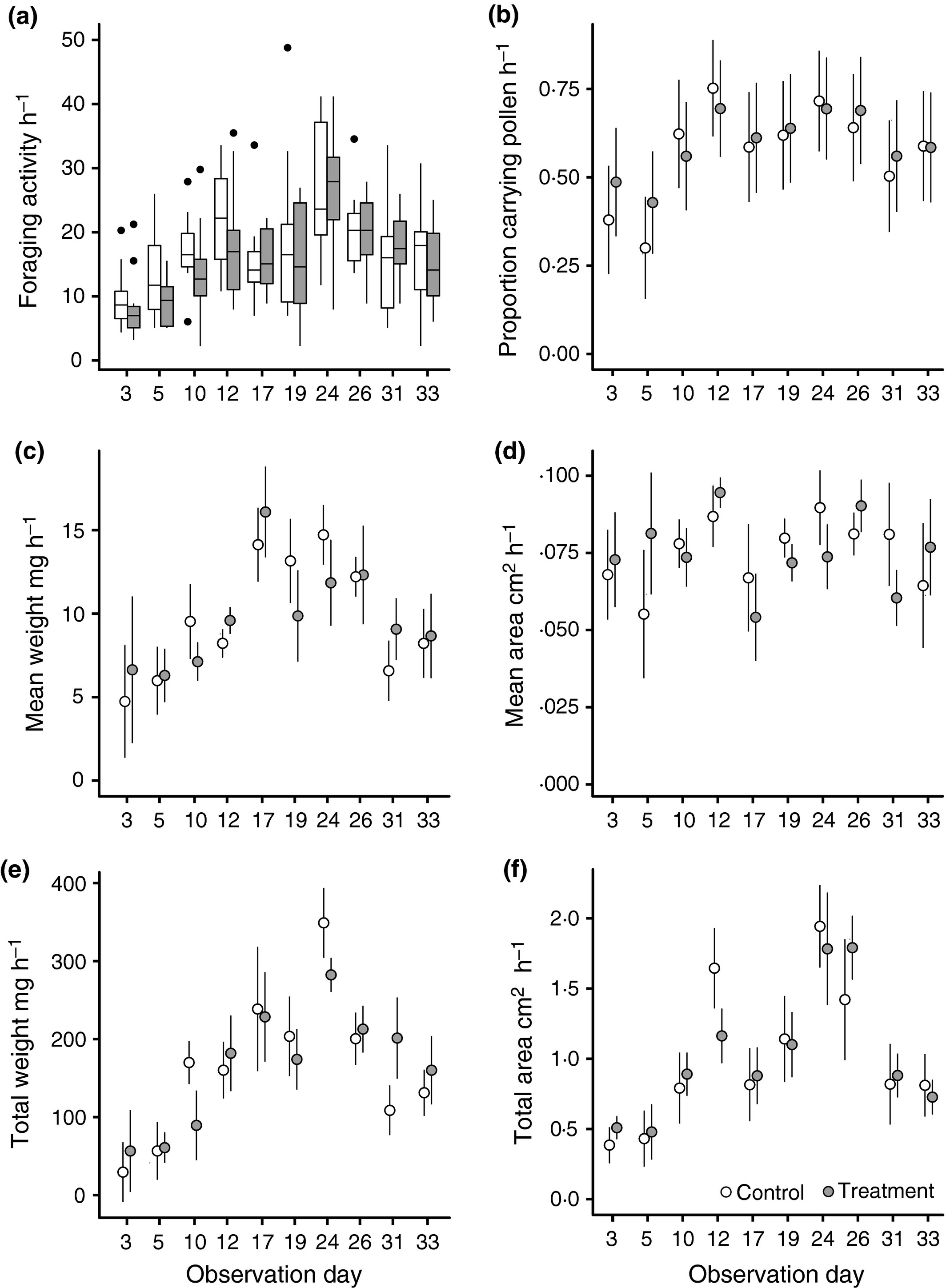

Foraging Across Days

We next investigated whether there were changes in daily foraging patterns across 5 weeks, aiming to elucidate any chronic effects caused by clothianidin treatment. Foraging activity over all colonies followed a parabolic pattern. In control colonies, we observed an average of 10 foraging bouts h-1 on day 3, increasing to 21 h-1 by day 19 followed by a decline to 14 h-1 by day 33; a relationship best described by fitting a polynomial relationship between foraging activity and observation day (GLMER: ‘Day’: Z = 7·742, P < 0·001; ‘Day2’: Z = −8·513, P < 0·001; Fig. 3a; Table S6a). The lack of a treatment or treatment by time interaction indicated that treated colonies made comparable numbers of foraging bouts throughout the experiment (Treatment: Z = −1·658, P = 0·097; ‘Treatment’ × ‘Day’: Z = 1·255, P = 0·209; ‘Treatment’ × ‘Day2’: Z = −0·64, P = 0·522).

Figure 3

Daily foraging activity across the 5-week experiment, plotted from the raw data: (a) box plots show foraging activity h-1 of observation; (b) mean proportion of foragers observed carrying pollen h-1; (c) mean weight of pollen brought back h-1; (d) total weight of pollen brought back h-1; (e) mean weight of pollen brought back h-1; (f) total area of pollen brought back h-1. Plots (a, b) relate to data collected by both observers, while (c–f) relates to data from each individual observer. Box plot central line indicates median value, box area represents the lower and upper quartiles, and whiskers indicate 95% CI. Error bars in (b–f) represent SEM.

The proportion of foragers observed carrying pollen also increased until approximately midway through the experiment before declining as the colony aged (GLMER: ‘Day’: Z = 6·527, P = <0·001; ‘Day2’: Z = −6·344, P < 0·001, Table S6b). The significant main effect of treatment indicated that, early in the experiment, foragers from treated colonies returned carrying pollen more frequently compared to control colonies (Z = 2·425, P = 0·0153), while the significant treatment by day interactions (‘Treatment’ × ‘Day’, Z = −2·368 P = 0·017; ‘Treatment’ × ‘Day2’, Z = 2·357, P = 0·018; Table S6b) showed that both the rate of increase and rate of decline were significantly lower for treated colonies resulting in less fluctuation in the proportion of foragers observed carrying pollen relative to control colonies (Fig. 3b).

The mean weight of pollen loads showed a curved relationship initially increasing then decreasing as the experiment progressed across colonies (LMER: ‘Day’: χ2 = 28·72, P < 0·001; ‘Day2’: χ2 = 25·73, P = 0·002; Fig. 3c). Foragers from treated colonies initially carried heavier pollen loads per foraging bout (χ2 = 27·63, P = 0·001) and increased the mean weight of pollen loads at a higher rate than control colonies (χ2 = 10·646, P = 0·005; Table S6c). Conversely, observer 2 found no effect of experimental day (LMER ‘Day’ χ2 = 3·571, P = 0·168; Table S6d) indicating that the mean area of pollen loads remained constant throughout the experiment (Fig. 3d). Observer 2 found that the mean area of pollen loads from foragers returning to treated colonies was significantly smaller than those returning to control colonies (χ2 = 7·193, P = 0·007) and, as we were unable to detect an interaction between treatment and observation day (χ2 = 3·024, P = 0·082), it remained so throughout the experiment.

Neither observer detected any effect of treatment nor a treatment by time interaction on either the total weight or area of pollen brought back per hour. However, they did find an initial increase in total weight and area of pollen collected in the early stages of the experiment followed by a decline as the colony aged, mirroring the combined effects of forager number and the proportion of pollen foraging workers (Weight: LMER: ‘Day’: χ2 = 27·952, P < 0·001; ‘Day2’: χ2 = 23·889, P < 0·001; Area: ‘Day’: χ2 = 21·502, P < 0·001; ‘Day2’, χ2 = 17·859, P < 0·001; Fig 3e,f; Table S6e,f).

Effect of Temperature and Wind on Foraging Behaviour

We found similar effects both within and between days, with higher wind speeds associated with increases in foraging activity (LMER: within day; Z = 3·117, P = 0·002), proportion of foragers carrying pollen (GLMER: within day; Z = 4·979, P < 0·001; between days; Z = 4·157, P < 0·001), the total weight of pollen (LMER: between days; Z = 109·16, P < 0·001) and total area (combined area) of pollen (LMER: between days; χ2 = 29·475, P < 0·001). Higher temperatures were associated with fewer foraging bouts (within day; Z = −3·067, P = 0·002; between days; χ2 = −4·894, P < 0·001) and a lower proportion of foragers carrying pollen (within day: Z = −2·549, P = 0·01; between days; χ2 = −2·047, P = 0·041); however, of the foragers observed carrying pollen, the average load size was larger at higher temperatures (within day: weight; χ2 = 21·934, P < 0·001; between days: mean area χ2 ≥ 11·094, P < 0·001).

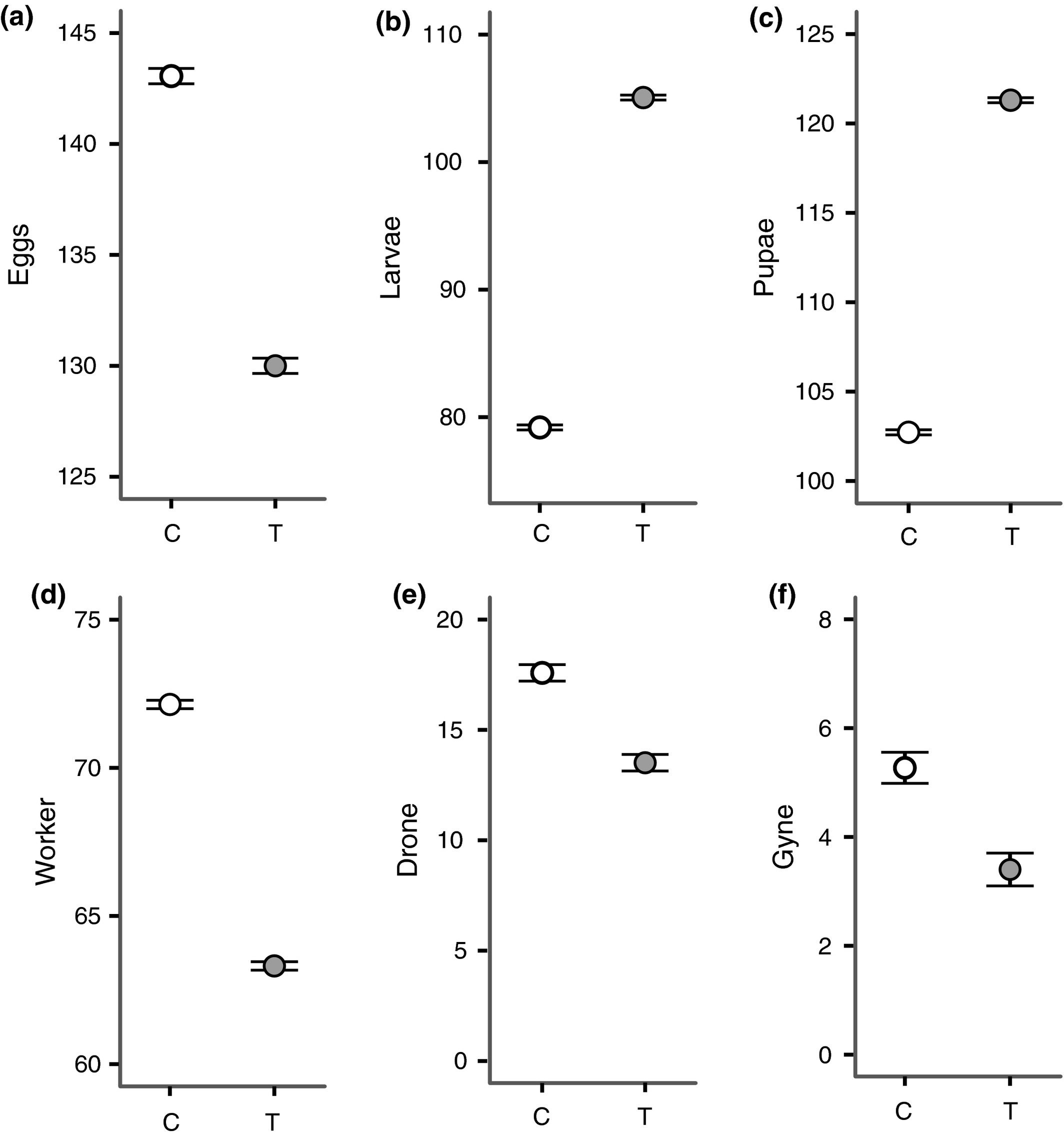

Brood Composition and Adult Census after 35 Days in the Field

All but one of the colonies increased in weight compared to the start, although we found no significant difference between control and treatment colonies in colony weight change (Table S7a). To see whether treatment induced changes to the demographic structure of the brood in colonies, we analysed the number of eggs, larvae and pupae separately. We found some differences in each of the life stages with treated colonies containing significantly fewer eggs, but significantly more larvae and pupae (All: Z = ≥2·87, P < 0·004, Fig. 4a–c, Table S7b–d). However, the similarity in colony weight gain and the inconsistent effect of treatment on the number of brood at three life stages makes it difficult to be confident to determine what, if any effect treatment had on brood development (see 4; for model outputs for colony weight and brood composition see Tables S2b and S7a–d). However, the effect of treatment on the number of adults showed a consistent pattern with fewer workers, drones and gynes within treated colonies after 35 days (All: Z ≥ 2·31, P ≤ 0·02; Table S7e–g, Fig. 4d–f).

Figure 4

Census measurements of colonies at the end of the 5-week experiment in the field. Graphs show the predicted mean (±SEM) values that were back transformed from the mixed effects model output (Table S7b–g) for the number of (a) eggs, (b) larvae, (c) pupae, (d) workers, (e) drones and (f) gynes, present in the colonies.

Discussion

Effect of Clothianidin Exposure

To date, few studies have investigated the effects of pesticide exposure on bee colonies under field settings. Our study, hence, contributes to this growing evidence base, but shows novelty by delivering known levels of pesticide exposure in a semi-field experiment while recording detailed information on foraging behaviour across time. In this experiment, clothianidin exposure initially increased the proportion of bees foraging for pollen in the early days of the experiment compared to control colonies; however, the proportion of control foragers returning with pollen increased rapidly to similar levels as treated colonies (Table S6b). Of these pollen foraging trips, while the pollen removal method found that treated returning foragers brought back heavier pollen loads, the photographic method found that treated returning foragers brought back marginally smaller pollen loads compared to control foragers (Table S6c,d). The results from the colony measurements at the end of the experiments were mixed; we found no difference in the weight gain of the colony and no clear pattern in the effects of clothianidin on the number of brood individuals (eggs, larvae and pupae) within the colony. However, by the end of the experiment treated colonies contained fewer workers, drones and gynes in comparison with control colonies. While we cannot determine if the reduction in the number of adults is due to the effect of direct exposure to clothianidin during development, indirect impairment to colony function (i.e. ability to rear brood) or loss of adult workers while foraging, it is interesting that our results are in agreement with previous semi-field (Gill, Ramos-Rodriguez & Raine 2012; Whitehorn et al. 2012; Moffat et al. 2016) and field studies (Goulson 2015; Rundlöf et al. 2015) in colonies exposed to a neonicotinoid.

Our behavioural results contrast with similar studies investigating the effects of imidacloprid and thiamethoxam, where chronic exposure produces obvious differences in foraging activity through time in treated colonies while simultaneously reducing the rate of pollen collection (Feltham, Park & Goulson 2014; Gill & Raine 2014; Stanley et al. 2015, 2016). An issue with our study is that we could not distinguish between a lack of motivation to collect pollen or impaired ability to collect pollen as we did not measure nectar foraging (i.e. we could not tell whether bees returning with nothing had crops containing nectar). However, we can still ask: why does the effect of clothianidin on bumblebee foraging behaviour apparently differ from the studies showing induced impairment from imidacloprid and thiamethoxam exposure? First, it is possible that environmental conditions during our five-week study did not impose strong enough constraints on foraging, and therefore, the treated colonies could buffer any clothianidin-induced effects. However, similar semi-field studies have reported large effects on foraging behaviour apparently under similar environmental conditions (Gill, Ramos-Rodriguez & Raine 2012; Feltham, Park & Goulson 2014; Gill & Raine 2014; Stanley et al. 2016), although admittedly the complexity of the landscape, the availability of floral resources and the interactions with other stressors make direct comparisons difficult. Secondly, in wild pollinator communities, the level of neonicotinoid exposure will vary depending on floral resource availability and the level of pesticide contamination in the environment affecting the acute and chronic doses that individuals receive over time. Using a method similar to Gill, Ramos-Rodriguez & Raine (2012), we tried to ensure our dosage was realistic by: (i) basing the concentration of clothianidin within the range reported from field samples (Table S1); (ii) allowing bees to forage on both provisioned sucrose and field nectar; and (iii) providing what we deemed to be half of the required sucrose the growing colonies required. Thirdly, the different neonicotinoids do not have a homogenous mode of action on bumblebee physiology and resultant behaviour. Although all neonicotinoids function as nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonists, there are sufficient structural differences between compounds to alter their toxicity to the same species of bee (Iwasa et al. 2004) and there is increasing evidence that different bee species/taxa, such as honeybees, solitary bees and bumblebees, vary in sensitivity to the same neonicotinoid (Goulson 2013; Arena & Sgolastra 2014; Laycock et al. 2014; Godfray et al. 2015; Rundlöf et al. 2015; Moffat et al. 2016).

To date, studies have largely focused on imidacloprid exposure, resulting in comparatively less research on the other neonicotinoids, despite the use of thiamethoxam and clothianidin significantly increasing in recent years (UK: Godfray et al. 2015). Of the studies exposing clothianidin and thiamethoxam at field realistic levels to bees (≤11 ppb) results have been mixed, with some studies on honeybees and bumblebees reporting little or no effect on colony success (Honeybees: Cutler & Scott-Dupree 2007; Cutler et al. 2014; Bumblebees: Franklin, Winston & Morandin 2004; Laycock et al. 2014; Scholer & Krischik 2014). Our finding that clothianidin causes only subtle behavioural changes to foraging is perhaps encouraging, however, we do still observe reductions in the number of adults within a colony, indicating that caution should still be taken when applying clothianidin onto flowering crops that are attractive to bumblebees (also see Rundlöf et al. 2015).

Bumblebee Foraging Ecology

Colonies maintained consistent levels of pollen collection throughout the day despite the foraging patterns showing more workers returning in the morning than afternoon. Our data show that any decrease in foraging activity later in the day is offset by an increase in both the proportion of foragers carrying pollen (also see: Free 1955), and the average amount brought back per foraging bout. While we did not measure nectar collection, previous research has shown that early morning bumblebee foraging activity concentrates more on gathering nectar (Free 1955; Peat & Goulson 2005), which is consistent with the pattern we observed. We further found that daily foraging activity showed a parabolic pattern over the course of the experiment mirroring the pattern of typical production of workers through a colony life cycle (Goulson 2010), and is what we might expect if the number of pollen foragers were a function of colony development stage.

Due to the design and nature of the experiment, we could not appropriately look for tri-interactions between treatment, time and wind speed or temperature. But we could look to see how wind and temperature influenced overall colony foraging activity across all 20 colonies. Perhaps counter-intuitively, given that wind speed is likely to increase energetic demands of flying insects (Niitepõld et al. 2009), we found that higher wind speeds correlated with increased foraging activity and pollen collection. Moreover, higher temperatures were associated with decreases in foraging activity at a colony level but with greater amounts of pollen brought back by individuals. A possible explanation could be that pollen may be drier and easier to collect under such conditions (Peat & Goulson 2005). Alternatively, it may be due to differences in weight distribution between carrying pollen and nectar loads, concentrating on collecting pollen at higher wind speeds to increase foraging performance relative to nectar (Mountcastle, Ravi & Combes 2015) which presumably offsets increased energetic costs of flying in windy conditions. Given the mild conditions during our experiment, temperature is unlikely to have placed a lower limit on foraging activity considering that bumblebees are known to cope well with low temperatures (Peat & Goulson 2005); in fact, we found that higher temperatures actually constrained foraging activity, resulting in fewer foraging individuals with a lower proportion concentrating on pollen.

Applied Benefits of our Study

While laboratory studies are invaluable tools to investigate causal effects, a common criticism is they represent unrealistic conditions. For instance, ‘true’ effects may be easily buffered if colonies are raised under ideal conditions (Godfray et al. 2014, 2015; Macfadyen et al. 2014), or exacerbated if colonies are fed exclusively on contaminated foods or experience an intensified and targeted application. Although recent studies have been designed to incorporate multiple stressors, either in the laboratory, such as combining pesticide by parasite interactions (Alaux et al. 2010; Vidau et al. 2011; Baron, Raine & Brown 2014; Fauser-Misslin et al. 2014; Brandt et al. 2016) or by operating partially in the laboratory and in the field (Whitehorn et al. 2012), it is still difficult to simulate environmental variability in the laboratory. More rarely, studies are conducted at a landscape scale under a ‘real-world’ scenario by placing bee colonies next to treated or untreated fields of flowering crops. Such ambitious studies should be applauded given the geographic scale required to prevent bees foraging on neighbouring fields (Rundlöf et al. 2015), but such an approach is expensive and logistically challenging. Furthermore, such studies can suffer from difficulty in controlling exposure to a single pesticide given the numerous chemicals applied in the environment with potential interactive effects (Thompson et al. 2013; Rundlöf et al. 2015) and providing appropriate replication is challenging (Pilling et al. 2013; Thompson et al. 2016). Although semi-field studies such as ours are not necessarily novel per se, they are underdeveloped for risk assessment (EFSA 2013b) and often rely solely on endpoint measurements. The incorporation of behavioural data into risk assessment is important for two reasons: (i) the influence of anthropomorphic stressors on pollinator behaviour could directly influence the ecosystem services that pollinators provide, although a recent paper showed that bumblebees chronically exposed to the neonicotinoid, thiamethoxam, did not reduce the pollination service provided compared to non-exposed bees (based on measures of fruit set and number of seeds; Stanley et al. 2015); (ii) behavioural changes may reveal the underlying mechanistic explanation behind changes in pollinator numbers or decreases in colony fitness.

Here we employed two separate methods for assessing pollen load, both of which have advantages. The pollen removal method allowed us to collect complete pollen loads throughout the experiment, and considering that pollen loads are not perfectly spherical, taking the mass of each collected pollen load is likely to provide a better estimate of pollen foraging performance than relying on the 2D surface area calculated using the photographic method. However, the removal method relies on an observer to handle the bees and collect the pollen – a process which is relatively time-consuming and labour intensive. In contrast, the photographic method is quick and simple to implement in the field. Interestingly, despite the pollen collection method appearing to be more invasive, we found no significant difference in the behaviour of foraging bees based on which of these two collection methods was used, allowing us to pool the data to measure foraging activity and the proportion of foragers carrying pollen (Table S8a–d).

In this study, the data collection involved minimal financial costs, but the collection regime was somewhat labour intensive, relying on the availability of two observers, which unfortunately limited the amount of time we could observe each colony. Furthermore, in our study, workers were not uniquely marked for identification, so we could not account for the degree of pseudoreplication (observing the same worker returning multiple times) unlike studies that individually tagged workers (Schneider et al. 2012; Feltham, Park & Goulson 2014; Gill & Raine 2014; Stanley et al. 2015; Thompson et al. 2016). However, given that our observations were carried out for one hour per day, the probability of counting the same individual more than twice is low, due to the time taken for a successful foraging bout (Gill, Ramos-Rodriguez & Raine 2012). Moreover, if we consider that the overall amount of pollen entering the colony is the most critical endpoint result, then regardless of which individuals are returning, it is likely that the total food income to the colony is what matters when focusing on colony growth (although see Perry et al. 2015). We propose that further development of our method towards automation, for example RFID and automated weighing scales (Feltham, Park & Goulson 2014) or the use of video or camera traps, could be utilized for behavioural assays to inform higher tier assessment of pesticides on social bees. Experiments like the one we present here provide a feasible and appropriate method to bridge the gap between laboratory and field experiments, allowing us to expose colonies with known levels of specific pesticides, in a comparable manner to laboratory studies, while exposing them to field realistic conditions to detect any colony level effects (Gill, Ramos-Rodriguez & Raine 2012). These data are important in aiding the conservation of social bee species and provide crucial insights into pesticide-induced changes to foraging behaviour; this is particularly important with the increasing need to mitigate threats to insect pollinator services (Gill et al. 2016).

Authors’ contributions

ANA, YW and RJG conceived the idea; ANA, TID, ER, ARR, TJC and RJG designed and conducted the experiment and/or carried out the analyses; ANA and RJG wrote the paper.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the technical assistance of Paul Beasley, and this work contributes to the Imperial College’s Grand Challenges in Ecosystems and the Environment that supports R.J.G.’s research. Funded by a Royal Society Research Grant (RG130455) awarded to R.J.G., and NERC grant (NE/L00755X/1) awarded to R.J.G. that supports A.N.A. and A.R.R.

Data accessibility

R scripts and data sets are uploaded to online supporting information and Dryad Digital Repository https://datadryad.org/stash/dataset/doi:10.5061/dryad.245kq (Arce et al. 2016).

Supporting Information

-

Fig. S1. Wooden nest box placed inside the plastic 110L box (390 × 685 × 440 mm) for protection in the field.

Fig. S2. Image taken by observer 2 (Thomas I. David) of a returning bee (forager) entering the colony through the transparent Perspex entrance tube.

Table S1. Selection of studies reporting mean levels and ranges of Clothianidin residues (in ppb) across a range of agricultural settings.

Table S2. (a) Census for each experimental colony prior to the start of the experiment, and (b) census at the end of the experiment after five weeks in the field. Colonies were assigned into ten pairs based on colony size (assessed by the number of workers and the number of pupae), and each pair was assigned to one of two observers using either a pollen removal method (removal of one pollen load), or photographic method (photograph taken of pollen load).

Table S3. Volume of provisioned sucrose consumed (to the nearest 0.5 mL) at the time of feeder replenishment (the volume of sucrose provisioned shows the volume provided two or three days prior to collection of the feeder).

Table S4. Example of an observer’s timetable for monitoring foraging behaviour for their 10 assigned colonies.

Table S5. Model outputs for LMER or GLMER for foraging during the day: (a) forager activity; (b) proportion of foragers bringing back pollen; (c) mean weight of pollen; (d) mean area of pollen; (e) total weight of pollen and; (f) total area of pollen.

Table S6. Model outputs for LMER or GLMER for foraging over the five weeks: (a) forager activity; (b) proportion of foragers bringing back pollen; (c) average weight of pollen; (d)average area of pollen; (e)total weight of pollen and; (f)total area of pollen.

Table S7. Model output for colony census. All models were LMER or GLMER, using a Gaussian or Poisson distribution.

Table S8. Model output for colony census including collection method as a fixed effect.

jpe12792-sup-0001-suppinfo.docx– [.DOCX, 2 MB] -

jpe12792-sup-0002-tables2_figa.png - [.PNG, 8.6 KB]

Please note: The publisher is not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting information supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing content) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

-

Alaux, C., Brunet, J.-L., Dussaubat, C., Mondet, F., Tchamitchan, S., Cousin, M. et al. (2010) Interactions between Nosema microspores and a neonicotinoid weaken honeybees (Apis mellifera). Environmental Microbiology, 12, 774– 782.

-

Arce, A.N., David, T.I., Randall, E., Rodrigues, A.R., Colgan, T.J., Wurm, Y. & Gill, R.J. (2016) Data from: Combining realism with control: impact of controlled neonicotinoid exposure on bumblebees in a realistic field setting. Dryad Digital Repository https://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.245kq.

-

Arena, M. & Sgolastra, F. (2014) A meta-analysis comparing the sensitivity of bees to pesticides. Ecotoxicology, 23, 324– 334.

-

Baron, G.L., Raine, N.E. & Brown, M.J.F. (2014) Impact of chronic exposure to a pyrethroid pesticide on bumblebees and interactions with a trypanosome parasite. Journal of Applied Ecology, 51, 460– 469.

-

Bates, D., Maechler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. (2015) Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67, 1– 48.

-

Biesmeijer, J.C., Roberts, S.P.M., Reemer, M., Ohlemüller, R., Edwards, M., Peeters, T. et al. (2006) Parallel declines in pollinators and insect-pollinated plants in Britain and the Netherlands. Science, 313, 351– 354.

-

Brandt, A., Gorenflo, A., Siede, R., Meixner, M. & Büchler, R. (2016) The neonicotinoids thiacloprid, imidacloprid, and clothianidin affect the immunocompetence of honey bees (Apis mellifera L.). Journal of Insect Physiology, 86, 40– 47.

-

Brown, M.J.F. & Paxton, R.J. (2009) The conservation of bees: a global perspective. Apidologie, 40, 410– 416.

-

Bryden, J., Gill, R.J., Mitton, R.A.A., Raine, N.E. & Jansen, V.A.A. (2013) Chronic sublethal stress causes bee colony failure. Ecology Letters, 16, 1463– 1469.

-

Burkle, L.A., Marlin, J.C. & Knight, T.M. (2013) Plant-pollinator interactions over 120 years: loss of species, co-occurrence, and function. Science, 339, 1611– 1615.

-

Cameron, S.A., Lozier, J.D., Strange, J.P., Koch, J.B., Cordes, N., Solter, L.F. & Griswold, T.L. (2011) Patterns of widespread decline in North American bumble bees. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 108, 662– 667.

-

Cutler, G.C. & Scott-Dupree, C.D. (2007) Exposure to clothianidin seed-treated canola has no long-term impact on honey bees. Journal of Economic Entomology, 100, 765– 772.

-

Cutler, G.C., Scott-Dupree, C.D., Sultan, M., McFarlane, A.D. & Brewer, L. (2014) A large-scale field study examining effects of exposure to clothianidin seed-treated canola on honey bee colony health, development, and overwintering success. PeerJ, 2, e652.

-

Desneux, N., Decourtye, A. & Delpuech, J.-M. (2007) The sublethal effects of pesticides on beneficial arthropods. Annual Review of Entomology, 52, 81– 106.

-

EFSA. (2013a) Conclusion on the peer review of the pesticide risk assessment for bees for the active substance clothianidin. EFSA Journal, 11, 3066– 3124.

-

EFSA. (2013b) Guidance on the risk assessment of plant protection products on bees (Apis mellifera, Bombus spp. and solitary bees). EFSA Journal, 11, 226.

-

Elbert, A., Haas, M., Springer, B., Thielert, W. & Nauen, R. (2008) Applied aspects of neonicotinoid uses in crop protection. Pest Management Science, 64, 1099– 1105.

-

Fauser-Misslin, A., Sadd, B.M., Neumann, P. & Sandrock, C. (2014) Influence of combined pesticide and parasite exposure on bumblebee colony traits in the laboratory. Journal of Applied Ecology, 51, 450– 459.

-

Feltham, H., Park, K. & Goulson, D. (2014) Field realistic doses of pesticide imidacloprid reduce bumblebee pollen foraging efficiency. Ecotoxicology, 23, 317– 323.

-

Fischer, J., Müller, T., Spatz, A.-K., Greggers, U., Grünewald, B. & Menzel, R. (2014) Neonicotinoids interfere with specific components of navigation in honeybees. PLoS One, 9, e91364.

-

Franklin, M.T., Winston, M.L. & Morandin, L.A. (2004) Effects OF Clothianidin on Bombus impatiens (Hymenoptera: Apidae) colony health and foraging ability. Journal of Economic Entomology, 97, 369– 373.

-

Free, J.B. (1955) The division of labour within bumblebee Colonies. Insectes Sociaux, 2, 195– 212.

-

Gallai, N., Salles, J.-M., Settele, J. & Vaissière, B.E. (2009) Economic valuation of the vulnerability of world agriculture confronted with pollinator decline. Ecological Economics, 68, 810– 821.

-

Gill, R.J. & Raine, N.E. (2014) Chronic impairment of bumblebee natural foraging behaviour induced by sublethal pesticide exposure. Functional Ecology, 28, 1459– 1471.

-

Gill, R.J., Ramos-Rodriguez, O. & Raine, N.E. (2012) Combined pesticide exposure severely affects individual- and colony-level traits in bees. Nature, 491, 105– 108.

-

Gill, R.J., Baldock, K.C.R., Brown, M.J.F., Creswell, J.J.E., Dicks, L.V., Fountaink, M.T. et al. (2016) Protecting an ecosystem service: approaches to understanding and mitigating threats to wild insect pollinators. Advances in Ecological Research, 53, 135– 206.

-

Godfray, H.C.J., Blacquière, T., Field, L.M., Hails, R.S., Petrokofsky, G., Potts, S.G., Raine, N.E., Vanbergen, A.J. & McLean, A.R. (2014) A restatement of the natural science evidence base concerning neonicotinoid insecticides and insect pollinators. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 281, 20140558.

-

Godfray, H.C.J., Blacquière, T., Field, L.M., Hails, R.S., Potts, S.G., Raine, N.E., Vanbergen, A.J. & McLean, A.R. (2015) A restatement of recent advances in the natural science evidence base concerning neonicotinoid insecticides and insect pollinators. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 282, 20151821.

-

Goulson, D. (2010) Bumblebees: Behaviour, Ecology, and Conservation. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

-

Goulson, D. (2013) An overview of the environmental risks posed by neonicotinoid insecticides. Journal of Applied Ecology, 50, 977– 987.

-

Goulson, D. (2015) Neonicotinoids impact bumblebee colony fitness in the field; a reanalysis of the UK’s Food & Environment Research Agency 2012 experiment. PeerJ, 3, e854.

-

Greenleaf, S.S. & Kremen, C. (2006) Wild bees enhance honey bees’ pollination of hybrid sunflower. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 103, 13890– 13895.

-

Henry, M., Béguin, M., Requier, F., Rollin, O., Odoux, J.-F., Aupinel, P., Aptel, J., Tchamitchian, S. & Decourtye, A. (2012) A common pesticide decreases foraging success and survival in honey bees. Science, 336, 348– 350.

-

Iwasa, T., Motoyama, N., Ambrose, J.T. & Roe, R.M. (2004) Mechanism for the differential toxicity of neonicotinoid insecticides in the honey bee, Apis mellifera. Crop Protection, 23, 371– 378.

-

Klein, A.-M., Vaissière, B.E., Cane, J.H., Steffan-Dewenter, I., Cunningham, S.A., Kremen, C. & Tscharntke, T. (2007) Importance of pollinators in changing landscapes for world crops. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 274, 303– 313.

-

Kremen, C. & Ricketts, T. (2000) Global perspectives on pollination disruptions. Conservation Biology, 14, 1226– 1228.

-

Laycock, I., Cotterell, K.C., O’Shea-Wheller, T.A. & Cresswell, J.E. (2014) Effects of the neonicotinoid pesticide thiamethoxam at field-realistic levels on microcolonies of Bombus terrestris worker bumble bees. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 100, 153– 158.

-

Lundin, O., Rundlöf, M., Smith, H.G., Fries, I. & Bommarco, R. (2015) Neonicotinoid insecticides and their impacts on bees: a systematic review of research approaches and identification of knowledge gaps. PLoS One, 10, e0136928.

-

Macfadyen, S., Banks, J.E., Stark, J.D. & Davies, A.P. (2014) Using semifield studies to examine the effects of pesticides on mobile terrestrial invertebrates. Annual Review of Entomology, 59, 383– 404.

-

Moffat, C., Buckland, S.T., Samson, A.J., McArthur, R., Chamosa Pino, V., Bollan, K.A., Huang, J.T.J. & Connolly, C.N. (2016) Neonicotinoids target distinct nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and neurons, leading to differential risks to bumblebees. Scientific Reports, 6, 24764.

-

Mountcastle, A.M., Ravi, S. & Combes, S.A. (2015) Nectar vs. pollen loading affects the tradeoff between flight stability and maneuverability in bumblebees. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 112, 5.

-

Niitepõld, K., Smith, A.D., Osborne, J.L., Reynolds, D.R., Carreck, N.L., Martin, A.P., Marden, J.H., Ovaskainen, O. & Hanski, I. (2009) Flight metabolic rate and Pgi genotype influence butterfly dispersal rate in the field. Ecology, 90, 2223– 2232.

-

Ollerton, J., Winfree, R. & Tarrant, S. (2011) How many flowering plants are pollinated by animals? Oikos, 120, 321– 326.

-

Peat, J. & Goulson, D. (2005) Effects of experience and weather on foraging rate and pollen versus nectar collection in the bumblebee, Bombus terrestris. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 58, 152– 156.

-

Perry, C.J., Søvik, E., Myerscough, M.R. & Barron, A.B. (2015) Rapid behavioral maturation accelerates failure of stressed honey bee colonies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 112, 3427– 3432.

-

Pilling, E., Campbell, P., Coulson, M., Ruddle, N. & Tornier, I. (2013) A four-year field program investigating long-term effects of repeated exposure of honey bee colonies to flowering crops treated with thiamethoxam. PLoS One, 8, e77193.

-

Potts, S.G., Biesmeijer, J.C., Kremen, C., Neumann, P., Schweiger, O. & Kunin, W.E. (2010) Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 25, 345– 353.

-

R Development Core Team. (2014) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.

-

Raine, N. & Chittka, L. (2007) Pollen foraging: learning a complex motor skill by bumblebees (Bombus terrestris). Naturwissenschaften, 94, 459– 464.

-

Raine, N.E. & Gill, R.J. (2015) Ecology: tasteless pesticides affect bees in the field. Nature, 521, 38– 40.

-

Rassband, W.S. (1997–2015) ImageJ. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

-

Rortais, A., Arnold, G., Halm, M.-P. & Touffet-Briens, F. (2005) Modes of honeybees exposure to systemic insecticides: estimated amounts of contaminated pollen and nectar consumed by different categories of bees. Apidologie, 36, 71– 83.

-

Rundlöf, M., Andersson, G.K.S., Bommarco, R., Fries, I., Hederstrom, V., Herbertsson, L. et al. (2015) Seed coating with a neonicotinoid insecticide negatively affects wild bees. Nature, 521, 77– 80.

-

Schneider, C.W., Tautz, J., Grünewald, B. & Fuchs, S. (2012) RFID tracking of sublethal effects of two neonicotinoid insecticides on the foraging behavior of Apis mellifera. PLoS One, 7, e30023.

-

Scholer, J. & Krischik, V. (2014) Chronic exposure of imidacloprid and clothianidin reduce queen survival, foraging, and nectar storing in colonies of Bombus impatiens. PLoS One, 9, e91573.

-

Stanley, D.A., Garratt, M.P.D., Wickens, J.B., Wickens, V.J., Potts, S.G. & Raine, N.E. (2015) Neonicotinoid pesticide exposure impairs crop pollination services provided by bumblebees. Nature, 528, 548– 550.

-

Stanley, D.A., Russell, A.L., Morrison, S.J., Rogers, C. & Raine, N.E. (2016) Investigating the impacts of field-realistic exposure to a neonicotinoid pesticide on bumblebee foraging, homing ability and colony growth. Journal of Applied Ecology, 53, 1440– 1449.

-

Thompson, H., Harrington, P., Wilkins, W., Pietravalle, S., Sweet, D. & Jones, A. (2013) Effects of neonicotinoid seed treatments on bumble bee colonies under field conditions. Available at: http://www.fera.co.uk/ccss/documents/defraBumbleBeeReportPS2371V4a.pdf.

-

Thompson, H., Coulson, M., Ruddle, N., Wilkins, S. & Harkin, S. (2016) Thiamethoxam: assessing flight activity of honeybees foraging on treated oilseed rape using radio frequency identification technology. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 35, 385– 393.

-

Vanbergen, A.J. & Insect Pollinators Initiative. (2013) Threats to an ecosystem service: pressures on pollinators. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 11, 251– 259.

-

Vidau, C., Diogon, M., Aufauvre, J., Fontbonne, R., Viguès, B., Brunet, J.-L. et al. (2011) Exposure to sublethal doses of fipronil and thiacloprid highly increases mortality of honeybees previously infected by Nosema ceranae. PLoS One, 6, e21550.

-

Whitehorn, P.R., O’Connor, S., Wackers, F.L. & Goulson, D. (2012) Neonicotinoid pesticide reduces bumble bee colony growth and queen production. Science, 336, 351– 352.

-

Winfree, R., Williams, N.M., Gaines, H., Ascher, J.S. & Kremen, C. (2008) Wild bee pollinators provide the majority of crop visitation across land-use gradients in New Jersey and Pennsylvania, USA. Journal of Applied Ecology, 45, 793– 802.

-

Winston, M.L. (1991) The Biology of the Honey Bee. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, USA.