Ants, Bees, Genomes & Evolution @ Queen Mary University London

Published: 14 June 2022

Convergent evolution of a labile nutritional symbiosis in ants

Raphaella Jackson, David Monnin, Patapios A Patapiou, Gemma Golding, Heikki Helanterä, Jan Oettler, Jürgen Heinze, Yannick Wurm, Chloe K Economou, Michel Chapuisat, Lee M Henry

The ISME Journal 16, pages 2114-2122, (2022)

Abstract

Ants are among the most successful organisms on Earth. It has been suggested that forming symbioses with nutrient-supplementing microbes may have contributed to their success, by allowing ants to invade otherwise inaccessible niches. However, it is unclear whether ants have evolved symbioses repeatedly to overcome the same nutrient limitations. Here, we address this question by comparing the independently evolved symbioses in Camponotus, Plagiolepis, Formica and Cardiocondyla ants. Our analysis reveals the only metabolic function consistently retained in all of the symbiont genomes is the capacity to synthesise tyrosine. We also show that in certain multi-queen lineages that have co-diversified with their symbiont for millions of years, only a fraction of queens carry the symbiont, suggesting ants differ in their colony-level reliance on symbiont-derived resources. Our results imply that symbioses can arise to solve common problems, but hosts may differ in their dependence on symbionts, highlighting the evolutionary forces influencing the persistence of long-term endosymbiotic mutualisms.

Introduction

Ants are among the most ecologically dominant organisms in terrestrial ecosystems, and part of their success lies in their ability to occupy a wide range of habitats. It has been suggested that acquiring nutrient-provisioning symbionts may have allowed certain ant lineages to survive in nutrient imbalanced habitats. For example, gut-associated bacteria are thought to have enabled transitions to arboreal lifestyles in several ant lineages by relaxing their need for nitrogen and allowing them to feed predominantly on plant-derived resources, such as extrafloral nectaries and insect honeydew [1,2,3]. Symbiont acquisitions may therefore represent key adaptations that have allowed ants to significantly expand the ecological niches in which they can forage and complete development, thereby contributing to their widespread ecological success.

At least four ant lineages have evolved symbioses where the microbes are housed within specialised cells called bacteriocytes that surround the midgut. Bacteriocytes are a common feature of ancient nutritional symbioses, where symbionts are essential for host development and strictly vertically transmitted through host generations [4]. The most well-studied bacteriocyte-associated symbiont in ants is Blochmannia, the obligate symbiont of Camponotus carpenter ants (Formicidae: Formicinae). Blochmannia provides its host with essential amino acids that can improve brood production, especially when proteins are scarce [1]. Blochmannia is also thought to aid hosts in nitrogen recycling and synthesises the aromatic amino acid tyrosine, which is essential for insect cuticle synthesis and other physiological processes such as melanisation and sclerotisation [5,6,7]. The symbiont of Cardiocondyla obscurior (Formicidae: Myrmicinae), Candidatus Westeberhardia cardiocondylae, hereafter Westeberhardia, despite having a highly reduced genome, has also retained the capacity to synthesise tyrosine through a shared metabolic pathway with its ant host [8]. Two additional ant genera, Formica and Plagiolepis, are also known to harbour symbionts within bacteriocytes surrounding the midgut, suggesting they also play a role in provisioning nutrients for their hosts [9,10,11]. However, the functional role of the symbionts in Formica and Plagiolepis is currently unknown.

While the acquisition of nutrient provisioning symbionts has allowed insects to repeatedly invade nutrient imbalanced niches, such as plant sap and blood feeding [12], it is less clear why these relationships evolve in predominantly omnivorous insects such as ants. Stable isotope analyses of Camponotus and Plagiolepis have suggested ants in these genera feed predominantly on plant-based resources [13]. Similarly, both Cardiocondyla and Formica commonly feed on honeydew and nectar [14, 15], and symbiont-carrying Formica species have been shown to occupy a lower trophic position than asymbiotic species [16]. This suggests that symbiont acquisitions may have facilitated convergent shift from omnivory to more plant-based diets in each of these ant lineages. However, it is currently unclear whether the symbioses have evolved to supplement the same vital nutrients limiting in their hosts’ diets. This has limited our understanding of the metabolic challenges facing omnivorous insects, and how nutritional symbioses evolve to overcome them.

The aim of this study is to determine whether the four bacteriocyte-associated symbioses in ants represent ancient nutritional mutualisms that have evolved to serve similar functions for their hosts. We first characterise the genomes of the symbionts in Formica and Plagiolepis, and several new strains of Westeberhardia from phylogenetically divergent Cardiocondyla lineages. Using a comparative approach, we asked whether the symbionts from all four ant lineages have retained metabolic pathways in their highly reduced genomes that suggest they serve similar nutrient-provisioning roles for their hosts. We then investigated the phylogenetic and intracolony distributions of symbionts in diverse Formica and Cardiocondyla species to determine the origins of each symbiosis and its prevalence across species and castes. This survey reveals that despite retaining their symbiont for millions of years, in many ant lineages that maintain multi-queen (polygynous) colonies, only a fraction of queens carry the symbiont, suggesting species differ in their dependence on symbiont-derived nutrients at the colony level. We present evidence that suggests species differences in symbiont retention are not correlated with changes in symbiont functionality and discuss how ant feeding ecology, sociality and cost-benefit trade-offs may impact dependence on nutritional symbioses.

Results and discussion

Genome characteristics of ancient obligate symbionts

We first tested the hypothesis that each of the ant lineages sequenced in our study (Cardiocondyla, Formica, and Plagiolepis) hosts its own ancient strictly vertically transmitted symbiont that have co-speciated with its host, which has been shown previously in the Camponotus- Blochmannia symbiosis [17]. To address this aim, we compared the genomes of symbionts from 13 species of ants, 8 from our study combined with 5 previously published genomes, representing four independently evolved symbioses. This includes symbionts from three Formica, two Plagiolepis, and an additional three Cardiocondyla species that we sequenced, in addition to four previously published genomes from Blochmannia, the obligate symbiont of Camponotus ants, and the one pre-existing Westeberhardia genome from Cardiocondyla obscurior [8,18,19,20,21].

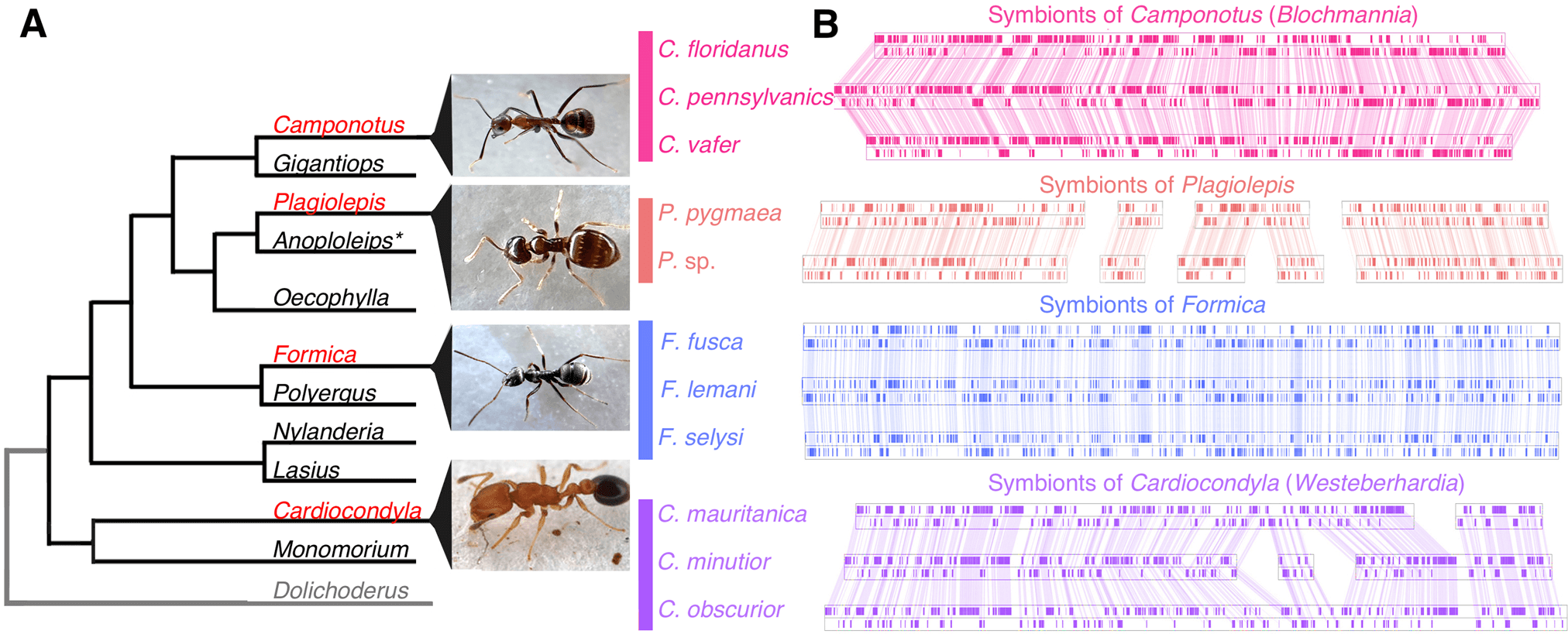

We found the gene order of single copy orthologs in symbionts is highly conserved in ant species belonging to the same genus (Fig. 1). This type of structural stability of genomes is typically found in symbionts that have been strictly vertically transmitted within a matriline [22] and has been documented in the obligate symbionts of whiteflies, psyllids, cockroaches, and aphids [23,24,25,26]. In contrast, genome structure differed substantially between symbionts from different ant genera (Fig. 1, Fig. S1). We also find that the host and symbiont phylogenies are in general concordance in Cardiocondyla (TreeMap: p = 0.00100 CI95% = [0.00000, 0.00424]), and in Formica the topologies suggest co-segregation, although there were too few nodes to confirm this statistically (Fig. S2). Together, this strongly suggests the symbioses in all four ant lineages are independently acquired ancient associations that have co-speciated with their hosts.

Fig. 1: Structural stability of ant symbiont genomes.

A Ant lineages known to host bacteriocyte-associated symbionts (red font) and lineages not known to (black font), based on [91]. Outgroup (grey font) not examined in this study. B Visualisation of symbiont genomes showing conservation of gene order in the symbionts of ant species that belong to the same genus. Blocks show the locations of single copy orthologs in the symbiont genome, lines connect shared single copy orthologs between genomes. All genomes and annotations were generated in this study except the Blochmannia symbionts and the Westeberhardia strain from C. obscurior [8, 18,19,20,21]. *Evidence of symbionts were detected in embryos of Anoplolepis [91] but it is unclear if they are localised in bacteriocytes in larvae and adults.

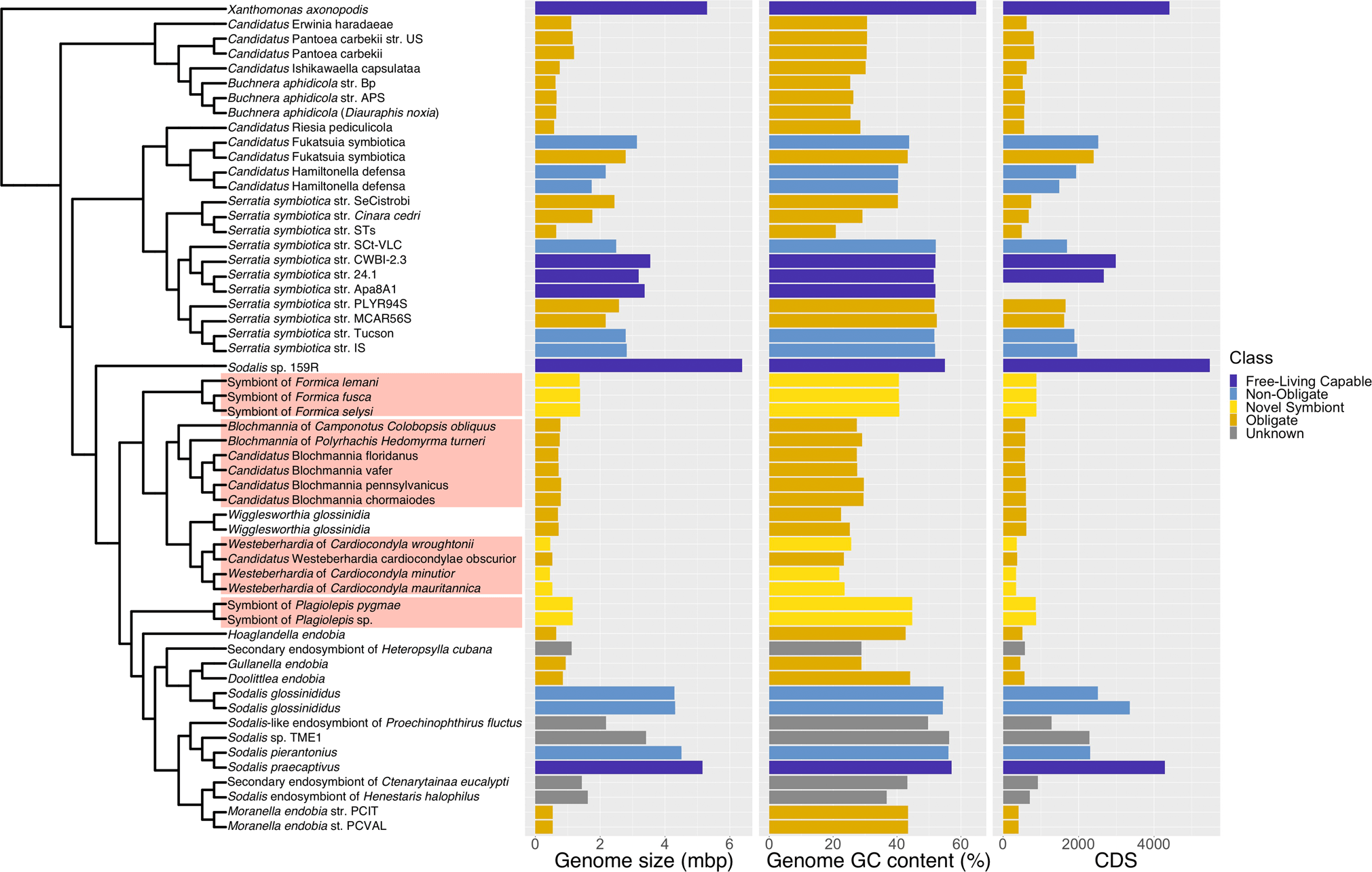

In addition, our phylogenetic analysis reveals that all four symbiont lineages originate from a single clade, the Sodalis-allied bacteria (Fig. 2). This demonstrates that ant lineages that host bacteriocytes-associated symbionts have convergently acquired related bacteria, which differs from previous findings based on limited taxa and genes [27]. All of the symbionts have evidence of advanced genome reduction, which is characterized by reduced genome size, GC content, and number of coding sequences, similar to other ancient obligate symbionts of insects [4]. The three strains of Westeberhardia we analysed have extremely small (0.45–0.53 Mb) GC depleted genomes (22–26%) that are similar to the figures reported for the strain in Cardiocondyla obscurior [8]; confirming that they have some of the smallest genomes of any known gammaproteobacterial endosymbiont (Fig. 2). By comparison, the symbionts in Formica and Plagiolepis have genomes around twice the size (1.37–1.38 Mb) and GC content (~41%) of Westeberhardia (Fig. 2) raising the possibility that they are in an earlier stage of genome reduction than both Westeberhardia and Blochmannia. The Formica and Plagiolepis symbionts have a similar size, GC range, and number of coding sequences as known obligate symbionts such as Candidatus Doolittlea endobia [28], and several Serratia symbiotica lineages that are co-obligate symbionts in aphids [29].

Fig. 2: Phylogenetic origins of the bacteriocyte-associated symbionts of ants.

A pruned phylogeny of gammaproteobacterial endosymbionts based on Fig. S8. The phylogeny is based on a dayhoff6 recoded amino acid alignment of 72 genes analysed using phylobayes. Bar plots represent the size (in Mbp) and GC content of symbiont genomes. Bars are colour coded to represent hypothesised relationships between symbionts and hosts. Species names highlighted in red in the phylogeny indicate the four bacteriocyte-associated symbionts of ants. Genomes sequenced and assembled for this paper are referenced as ‘novel symbiont’ lineages. Full phylogenies with node support and branch lengths are available as Fig. S8 and Fig. S9, respectively.

Bacteriocyte-associated endosymbionts

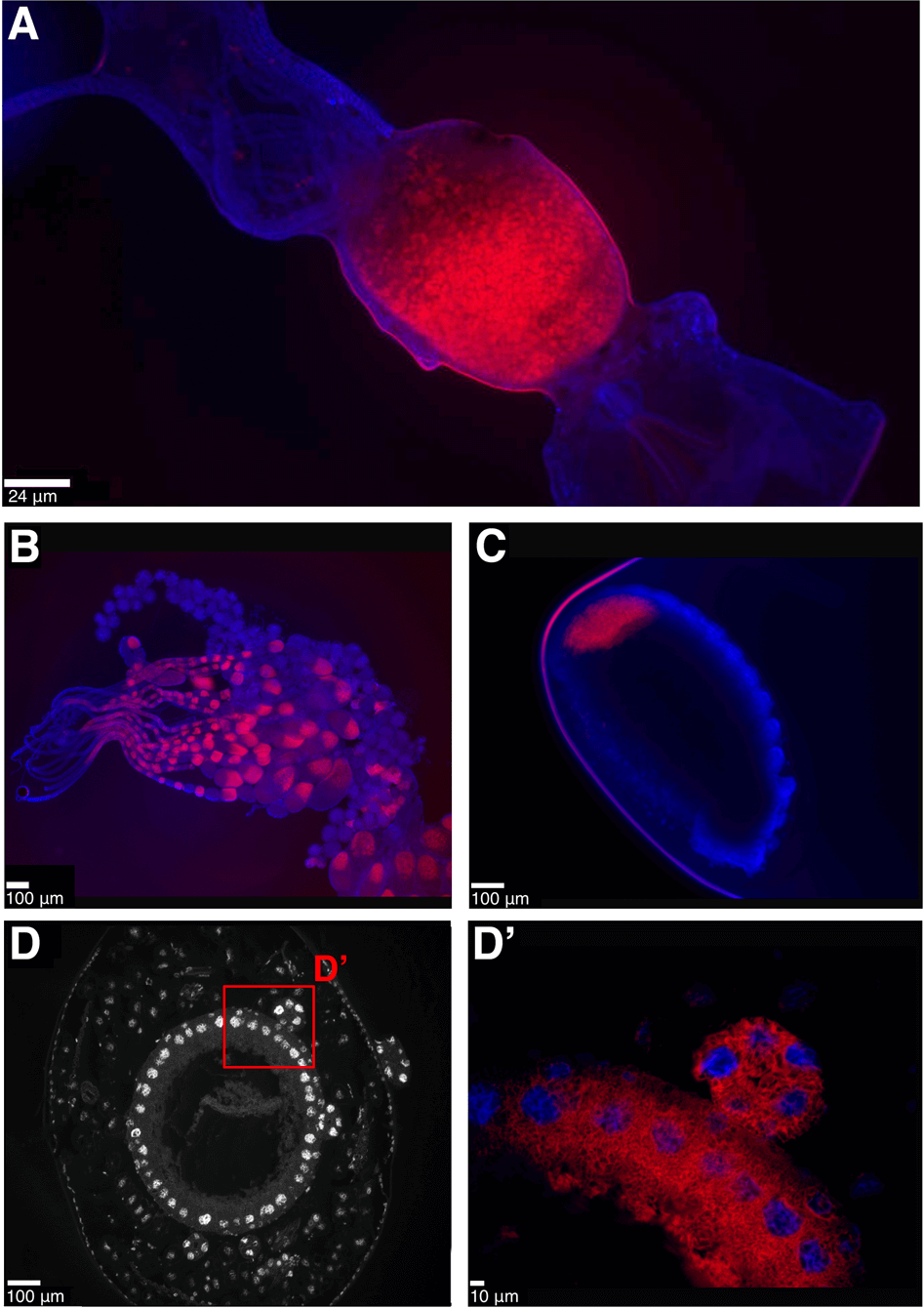

Using fluorescent in situ hybridisation, we determine whether the Sodalis-allied symbionts we sequenced are localised in bacteriocytes to confirm they are the associations first observed by Lillienstern and Jungen in the early 1900’s [10, 11].

Consistent with Lilienstern’s findings [11], we found the Sodalis symbiont in Formica ants is distributed in bacteriocytes surrounding the midgut in adult queens (Fig. 3A). The symbionts are also found in eggs and ovaries of adult queens, indicating they are vertically transmitted from queens to offspring (Fig. 3B–C). Sectioning of F. cinerea larvae shows the bacteriocytes to be arranged in a single layer of cells surrounding the midgut, as well as in clusters of bacteriocytes closely situated to the midgut (Fig. 3D–D’). In adult Plagiolepis queens, the symbiont was not present in bacteriocytes around the midgut, suggesting the symbiont may play a more substantive role in larval development or pupation and then migrates to the ovaries prior to or during metamorphosis. Apart from that, the localisation of the symbiont in Plagiolepis was the same as in Formica – symbionts in larval midgut bacteriocytes, ovaries and eggs (Fig. S3) – supporting Jungen’s cytological findings [10]. Bacteriocytes are also found surrounding the midgut in Camponotus and Cardiocondyla ants [8, 30, 31] indicating the symbionts are localised in a similar manner in all four ant lineages.

Fig. 3: Anatomical localisation of symbiont in Formica ants.

Fluorescent in situ hybridisation (FISH) generated images showing the localisation of symbionts in Formica ants. A–C Whole mount FISH of Formica fusca: queen gut (A, crop and proventriculus on the right, midgut in the middle, hindgut and Malpighian tubules on the left), ovaries (B) and egg (C). DAPI staining of host tissue in blue, symbiont stained in red. D–D'. FISH on transverse cytological sections of Formica cinerea larva midgut. DAPI staining only, showing host nuclei of bacteriocytes in a single layer surrounding the midgut (D), and a magnified region highlighting symbionts in red localised within bacteriocytes and in a bacteriome (D’). A FISH image of the symbiont-free midgut of a Formica lemani queen is available as Fig. S11.

Conservation of metabolic functions in ant endosymbionts

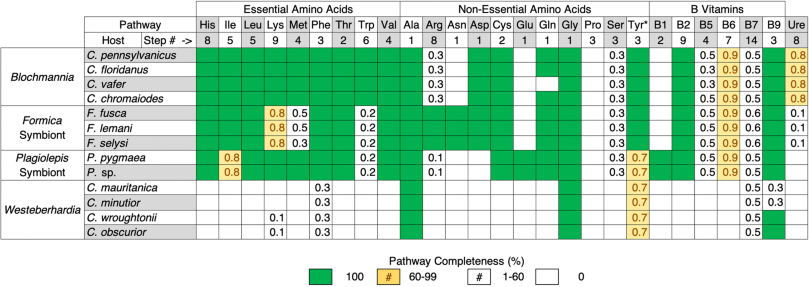

Despite on-going genome reduction, obligate symbionts of insects typically retain gene networks required for maintaining the symbiosis with their host, such as pathways for synthesising essential nutrients. This has resulted in the symbionts of sap- and blood-feeding insects converging on genomes that have retained the same sets of metabolic pathways – to synthesise essential nutrients missing in their hosts’ diets [32, 33]. Here we compare the metabolic pathways retained in the reduced genomes of the four bacteriocyte-associated symbionts of ants to test the hypothesis that have been acquired to perform similar functions. For this, we assess whether they have consistently retained metabolic pathways to synthesise the same key nutrients. Two major patterns stand out.

The first major pattern we find is that the four ant symbionts have all retained the shikimate pathway, which produces chorismate, along with most of the steps necessary to produce tyrosine from this precursor (Tables 1 and S2). Both the symbiont of Formica and Westeberhardia each lack one of the genes required to produce tyrosine. However, in Westeberhardia it is believed the host encodes the missing gene, supplying the enzyme to fulfil the final step of the pathway [8]. Intriguingly, we find that this gene is also present in the Formica ant genomes (Fig. S4). In addition, all symbionts except Westeberhardia can produce phenylalanine which is a precursor that can be converted to tyrosine by their hosts [5, 34, 35]. Tyrosine is important for insect development as it is used to produce L-DOPA, which is a key component of insect cuticles [5]. Tyrosine is also a precursor for melanin synthesis, which is important in protection against pathogens, and plays a fundamental role in neurotransmitters and hormone production [36, 37]. In several species of ants, weevils, and other beetles, symbionts are believed to provision hosts with tyrosine, and it has been shown experimentally in several of these species that removal or inhibition of their symbionts causes cuticle development to suffer [38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47]. A thicker cuticle has been shown to help symbiont-carrying grain beetles resist desiccation [43], and defend against natural enemies [48]. However, female reproduction is delayed at higher humidity, suggesting a metabolic cost to carrying their Bacteroidetes symbiont. Tyrosine provisioning is also the likely function of Westeberhardia in Cardiocondyla ants, as this is one of the few nutrient pathways retained in this symbiont. Our analysis confirms the shikimate pathway, and the symbiont portions of the tyrosine pathway, have been retained in Westeberhardia from three phylogenetically diverse Cardiocondyla lineages, providing additional support for this hypothesis. In addition to tyrosine, most of the symbionts have retained the capacity to produce vitamin B9 (tetrahydrofolate) and all can perform the single step conversions necessary to produce alanine and glycine. However, our gene enrichment analysis indicates that tyrosine, and the associated chorismate biosynthetic process, are the only enriched vitamin or amino acid pathways that are shared by all of the symbiont genomes (Table S1). This suggests that provisioning of tyrosine by symbionts, or tyrosine precursors, is of general importance across all bacteriocyte-associated symbioses of ants.

Table 1 – Comparison of the retention and losses of metabolic pathways for key nutrients across ant symbionts.

Pathways displayed are based on those that have been shown to play important roles in other ant and insect symbioses. Detailed breakdowns of these nutrient pathways along with analysis of other precursor, core metabolite synthesis, and transcriptional pathways, are available in Table S2. *Tyrosine is considered a non-essential amino acid because it can be synthesised by most eukaryotic hosts from phenylalanine.

The second major pattern emerging from our comparative analysis is that there are clear differences in the pathways lost or retained across symbionts (Tables 1 and S2). This is most evident when comparing Blochmannia with Westeberhardia, the latter of which has lost the capacity to synthesise most essential nutrients. The symbionts of Formica or Plagiolepis, in contrast, have retained the capacity to synthesise many of the same amino acids and B vitamins as Blochmannia, suggesting they may perform similar functions for their hosts. However, Blochmannia has retained more biosynthetic pathways, particularly those involved in the synthesis of essential amino acids. Previous experimental studies have confirmed that Blochmannia provisions hosts with essential amino acids [1]. The absence of several core essential amino acids in the Formica and Plagiolepis symbionts may reflect differences in the dietary ecology of the different ant genera. The retention of the full complement of essential amino acids biosynthetic pathways in the highly reduced genome of Blochmannia does however indicate it plays a more substantive nutrient-provisioning role for its hosts than the other ant symbionts we investigated.

Previous work on the extracellular gut symbionts of several arboreal ant lineages identified nitrogen recycling via the urease operon as a function that may be of key importance for ant symbioses [1, 2, 49, 50]. However, we do not find any evidence that the symbionts of Formica, Plagiolepis, or Cardiocondyla play a role in nitrogen recycling via the urease operon (Table 1). This suggests that nitrogen recycling may play an important role for more strictly herbivorous ants, such as Cephalotes. Our results indicate tyrosine supplementation by symbionts may be universally required for essential physiological process across a broader range of ant lineages.

The origins and losses of symbioses in Formica and Cardiocondyla

We investigated the presence of the symbiont in phylogenetically diverse Formica and Cardiocondyla species to identify the evolutionary origins and losses of the symbiosis. Although the symbiont in Plagiolepis was present in P. pygmaea and two unknown Plagiolepis species we investigated, we did not have sufficient phylogenetic sampling to assess the origins of the symbiosis.

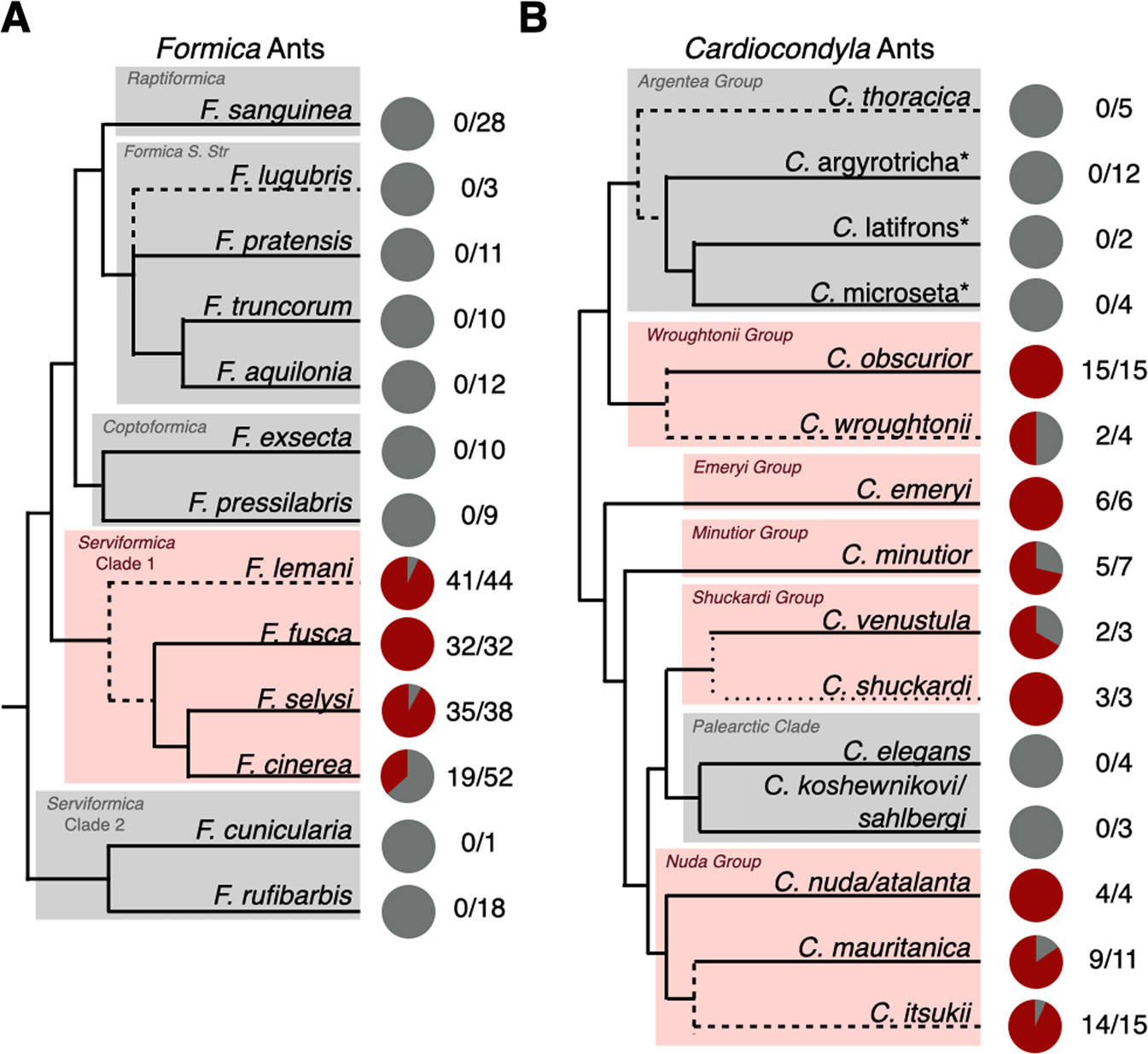

In Formica, we find the symbiont is restricted to a single clade in the paraphyletic Serviformica group (Fig. 4A). The species in this clade are socially polymorphic, forming both multi-queen and single-queen colonies [51]. Based on a previously dated phylogeny of Formica ants, we estimate the symbiosis originated approximately 12–22 million years ago [52]. In Cardiocondyla, the symbiosis is widespread throughout the genus. The prevalence of the symbiont in Cardiocondyla, in combination with its highly reduced genome, suggests it is a very old association that likely dates back to the origins of the ant genus some 50–75 million years ago [53]. The symbiont was also absent in two clades, the argentea and palearctic groups (Fig. 4B). This may represent true evolutionary losses in these clades. It may be that these losses are linked to a notable change in social structure in these two Cardiocondyla clades, having gone from the ancestral state of maintaining multi-queen colonies to single-queen colonies [54], however it is not clear how this could impact the symbiosis.

Fig. 4: Phylogenetic distribution of symbionts in queens of Formica and Cardiocondyla ants.

Pie charts represent the proportion of Formica (A) and Cardiocondyla (B) queens sampled that carried the symbiont (red) and those that did not (grey). Numbers represent the number of queens positive for the symbiont over the total number of queens sampled (intracolony infection frequencies in Table S5). See the supplementary material for the statistical testing of differences in prevalence within Serviformica Clade 1. The Formica phylogeny is based on [81] and the Cardiocondyla phylogeny is based on [83], with major clades highlighted. Dashed lines indicate species added to the original source phylogeny based on additional published phylogenies (specified in the Taxonomic Analysis section of the methods). Starred names are provisional names of a recognised morphospecies to be described by B. Seifert.

Evidence of variation in colony-level dependence on symbionts

Observations from individual studies on F. cinerea and F. lemani [10, 11], as well as Cardiocondyla obscurior [8], reported rare cases of ant queens not harbouring their symbionts in nature. This called into question the degree to which these insects depend on symbionts for nutrients, and whether the symbiosis may be breaking down in certain host lineages. However, given the limited number of species and populations studied, it is unclear how often colonies are maintained with uninfected queens, and whether this varies across species, suggesting species may differ in their dependence on their symbiont. To answer this question, we assessed the presence of the symbionts in 838 samples from 147 colonies of phylogenetically diverse Formica and Cardiocondyla species collected across 8 countries.

Our investigation reveals the natural occurrence of uninfected queens is a widespread phenomenon in many Formica and Cardiocondyla species (Fig. 4). We confirmed the absence of symbionts in queens, and that they have not been replaced with another bacterial or fungal symbiont, using multiple approaches including diagnostic PCR, metagenomic and deep-coverage amplicon sequencing (Tables S3, S4, Figs. S5, S6). Wolbachia was high in relative abundance, especially in Formica ants, but was not sufficiently present across samples to be a feasible replacement. There was also clear evidence of variation across host species. In Formica, queens and workers of F. fusca always carried the symbiont, whereas queens and workers of F. lemani, F. cinerea, and F. selysi showed varying degrees of individuals not carrying the symbionts (Fig. 4A, Table S5). A similar pattern can be seen in Cardiocondyla, where queens of several species, such as C. obscurior, always carry the symbiont, compared to lower incidences in other species (Fig. 4B). Klein et al [8] identified a single C. obscurior colony with uninfected queens in Japan. However, queens of this species nearly always carry the symbiont in nature.

The degradation and eventual loss of symbionts from bacteriocytes has been reported in males, and in sterile castes of aphids and ants [55], which do not transmit symbionts to offspring. In reproductive females, bacteriocytes may degrade as a female ages; however, symbionts are typically retained at high bacterial loads in the ovaries, as this is required to maintain the symbionts within the germline [31]. All of the symbiotic ant species we investigated maintain multi-queen colonies, and the vast majority had at least one queen, often more, within a colony that carried the symbiont (Table S5). We hypothesize that species that maintain colonies with uninfected queens may be able to retain sufficient colony-level fitness with only a fraction of queens harbouring the symbiont and receiving its nutritive benefits.

Dependence on symbionts in a socioecological context

The retention of symbionts in queens and workers of some species, but not others, suggests species either differ in their dependence on symbiont-derived nutrients, or that symbionts have lost the capacity to make nutrients in certain host lineages. Our analysis of symbiont genomes did not reveal any structural differences, such as the disruption of metabolic pathways, which could explain differences in symbiont retention between host species (Table S2). This suggests differences in the retention of symbionts may reflect differences in host ecologies.

In ants, which occupy a wide range of feeding niches, reliance on symbiont-derived nutrients will largely depend on lineage-specific feeding ecologies. For example, several species of arboreal Camponotus ants have been shown to be predominantly herbivorous [56]. Blochmannia, in turn, has retained the capacity to synthesise key nutrients lacking in their plant-based diets, such as essential amino acids [1]. Blochmannia is also always present in queens and workers [31], which is a testament to the importance of these nutrients for the survival of its primarily herbivorous host [13]. In contrast, Formica and Cardiocondyla species are thought to have a more varied diet [14]. Diet flexibility and altered foraging efforts may therefore reduce their reliance on a limited number of symbiont-derived nutrients allowing colonies of some species to persist with uninfected queens in certain contexts. Silvanid beetles and grain weevils, for example, can survive in the absence of their tyrosine-provisioning symbionts [38, 57, 58] when provided nutritionally balanced diets, in the laboratory [57] or in cereal grain elevators [59, 60]. Similarly, studies on Cardiocondyla and Camponotus ants have shown they can maintain sufficient colony health in the absence of their symbionts, if provided a balanced diet [31, 61]. It would be interesting to know whether species of Formica and Cardiocondyla that always carry the symbiont in nature, such as F. fusca and C. obscurior, have more restricted diets with less access to nutrients such as tyrosine, as this may explain their dependence on their symbiont for nutrients and tendency to harbour them in queens.

Although it is unusual for bacteriocyte-associated symbionts to be absent in reproductive females, the fact that it is simultaneously occurring in phylogenetically diverse species from many locations suggests the symbiosis may have persisted in this manner over evolutionary time. Perhaps through diet flexibility colonies can be maintained with uninfected queens in some contexts, however we expect them to be disadvantaged in other ecological scenarios. Fluctuating environmental conditions may therefore eventually purge asymbiotic queens from lineages, allowing the symbiosis to be retained over longer periods of evolutionary time. The multiple-queen colony lifestyle in all symbiotic Formica and Cardiocondyla species we investigated may also provide an additional social buffer that limits the costs to individual queens being asymbiotic. Workers will still nourish larvae and queens without symbionts and colony fitness may be maintained through the reproductive output of nestmate queens that carry the symbiont. There may also be an adaptive explanation for the losses if, for example, metabolic costs to maintain the symbiosis trade off in a context dependent manner [44, 62, 63]. Under this scenario, maintaining a mix of infected and uninfected queens may benefit a colony by allowing for optimal reproduction under a broader range of environmental scenarios.

Our data suggest that symbiotic relationships can evolve to solve common problems but also rapidly break down if the symbiosis is no longer required, or potentially when costs are too high [44]. We have identified tyrosine provisioning as a possible unifying function across bacteriocyte-associated symbionts of ants. But we have also shown species can vary in how much they depend on symbionts for nutrients. Our results demonstrate that ants have a unique labile symbiotic system, allowing us to better understand the evolutionary forces that influence the persistence and breakdown of long-term endosymbiotic mutualisms.

Candidatus Liliensternia hugann and Candidatus Jungenella plagiolepis

We propose the names Candidatus Liliensternia hugann for the Sodalis-allied symbiont found in Formica. The genus name is in honour of Margarete Lilienstern who first identified the symbiont [11]. The species name is derived from the combined first names of the first authors parents. Similarly, we propose the name of Candidatus Jungenella plagiolepis for the Plagiolepis-bound symbiont. The genus name is in honour of Hans Jungen who originally discovered the symbiont [10], and the species name is derived from Plagiolepis, the genus in which the symbiont can be found.

Materials and methods

Detailed protocols for each of the following sections are available in the Supplementary Materials, under Supplementary Methods.

Metagenomic sequencing and analysis

Single queens from 16 different species of Formica, Plagiolepis, and Cardiocondyla, were sequenced using the HiSeq 4000 (Illumina). Of these samples, 8 queens from 3 Formica species (fusca, lemani, selysi), 2 Plagiolepis species (pygmaea, spp.), and 3 Cardiocondyla species (minutior, mauritanica, wroughtonii) carried the symbiont of interest at sufficient coverage for metagenomic assembly. Raw reads were trimmed and then subjected to two rounds of filtering, metagenomic binning, and assembly using SPAdes V3.11.1 [64]. Blobplots of contigs graphed by coverage and GC content and coloured by taxonomic identification are available as Fig. S7. Genomes were annotated using Prokka V1.14.6 [65]. Pathway completeness was assessed using manual curation and the metacyc resources for E. coli str. K-12 [66]. Single copy orthologs were identified using Orthofinder V2.2.7 [67]. Enriched functional categories and pathways were identified using David [68, 69].

Taxonomic analysis and congruence testing

The phylogeny of ant genera (Fig. 1) is based on a previous analysis [70] with additional tip placements based on [53]. The phylogeny of endosymbiont species (Fig. 2) is a pruned version of the full phylogeny (Fig. S8). The full phylogeny was created using the protocol developed by Husnik et al. [71] to optimally resolve phylogenetic relationships of gammaproteobacteria endosymbionts, because they are known to be difficult to resolve. We used GtoTree [72] to generate an alignment of 72 core gammaproteobacterial genes. This alignment was then recoded using Dayhoff6 recoding using phylogears2 v2.0.x [73]. The phylogeny was then generated with phylobayes v4.1b [74,75,76,77] using cat and gtr settings. Model fit and convergence was assessed using Tracer v.1.2.7 [78] and Phylobayes’s bcomp function. We followed Phylobayes’s recommendations that maxdiff should be less than 0.3 (maxdiff was 0.255185). A consensus tree was generated using two chains that had run for 30,000 iterations with a burn in of 3000, sampling every 10 iterations. Free-living relatives of symbionts were selected based on a previous phylogeny of the Enterobacteriales [71, 79].We tested congruence between host and symbiont phylogenies using TreeMap 3b [80].

The phylogeny of ant species (Fig. 4) is based on a previous analysis of ant species [81] with additional tip placements based on a phylogeny of cytochrome B sequences of ants [82] (including sequences from individuals we had sequenced for Formica (Fig. S10)) and a phylogeny for Cardiocondyla [83] with additional tip placements based on a different phylogeny of Cardiocondyla [84].

FISH microscopy

FISH was performed on eggs, queen guts, queen ovaries (whole mount), and on larvae (cytological sections), using 16 S rRNA oligonucleotide probes specifically targeting the symbionts. The probes used were 5’-Cy3-CGCTACACCTGAAATTCT-3’ for the Formica symbiont, or 5’-Cy3-CGCTACACCTGGAATTCT-3’ for the Plagiolepis symbiont. Following overnight incubation at room temperature, the samples were mounted using Vectashield hardset antifade mounting media with DAPI and visualised using a Leica DMRA2 epi-fluorescent microscope. Detailed protocol can be found in the Supplementary Materials, under Supplementary Methods.

Symbiont screening procedure

We screened 838 individuals, a mixture of queens and workers, from 147 colonies across 29 species for the presence of symbionts using a combination of diagnostic PCR screening and 16 S rRNA deep coverage sequencing (Table S3). Diagnostic PCRs were carried out by amplifying the symbiont 16 S rRNA genes from total genomic DNA extracted from individual ants. Custom primer pairs (Table S5) were used for screening Sodalis and Westeberhardia, respectively. Positive queen diagnostic PCR results were confirmed using Sanger sequencing.

For 16 S rRNA deep coverage sequencing, the 515 F/806 R primer pair [85] was used to amplify the V4 region of the 16 S rRNA gene in two runs of 16 S rRNA sequencing in 177 Cardiocondyla and Formica samples (Table S3). Additionally we conducted a run of ITS fungal sequencing using the ITS5/5.8S fungi primer pair [86] (Table S3), to investigate whether any fungal symbiont replacement could be detected. Samples contain trace amounts of symbiont reads after multiplex 16 S rRNA sequencing were reanalysed using targeted qPCR, and diagnostic PCR, with symbiont-specific primers, to confirm the symbiont was indeed absent. The qPCR validation was conducted on samples from symbiont carrying, and non-symbiont carrying species.

16 S rRNA gene sequencing data were analysed using Mothur v.1.41.3 [87], to cluster reads into OTUs at 99% similarity. ITS sequencing data were analysed using USEARCH [88] and UPARSE [89] to cluster reads in zero-radius OTUs (ZOTUs). Data were then processed using R to remove OTUs/ZOTUs at below 1 percent relative abundance in a sample and generate visualizations.

We chose a threshold of 1 percent relative abundance, as we found the symbiont was not detectable by targeted PCR or qPCR using symbiont-specific primers at this level.

Data availability

All data collected in association with this paper, alongside associated genome assemblies, are available under BioProject accession PRJNA639935.

References

-

Feldhaar H, Straka J, Krischke M, Berthold K, Stoll S, Mueller MJ, et al. Nutritional upgrading for omnivorous carpenter ants by the endosymbiont Blochmannia. BMC Biol. 2007;5:48.

-

Russell JA, Moreau CS, Goldman-Huertas B, Fujiwara M, Lohman DJ, Pierce NE. Bacterial gut symbionts are tightly linked with the evolution of herbivory in ants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:21236–41.

-

Sanders JG, Lukasik P, Frederickson ME, Russell JA, Koga R, Knight R, et al. Dramatic differences in gut bacterial densities correlate with diet and habitat in rainforest ants. Integr Comp Biol. 2017;57:705–22.

-

Moran NA, McCutcheon JP, Nakabachi A. Genomics and evolution of heritable bacterial symbionts. Annu Rev Genet. 2008;42:165–90.

-

Hopkins TL, Kramer KJ. Insect cuticle sclerotization. Annu Rev Entomol. 1992;37:273–302.

-

Whitten MMA, Coates CJ. Re-evaluation of insect melanogenesis research: Views from the dark side. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2017;30:386–401.

-

Vavricka CJ, Han Q, Mehere P, Ding H, Christensen BM, Li J. Tyrosine metabolic enzymes from insects and mammals: a comparative perspective. Insect Sci. 2014;21:13–9.

-

Klein A, Schrader L, Gil R, Manzano-Marín A, Flórez L, Wheeler D, et al. A novel intracellular mutualistic bacterium in the invasive ant Cardiocondyla obscurior. ISME J. 2016;10:376–88.

-

Buchner P. Endosymbiosis of animals with plant microorganisms: revised English version. New York: Intersci Publ; 1965.

-

Jungen H. Endosymbionten bei Ameisen. Insectes Soc. 1968;15:227–32.

-

Lilienstern M. Beiträge zur Bakteriensymbiose der Ameisen. Z. Morph. u. Okol. Tiere. 1932;26:110–34.

-

Zientz E, Dandekar T, Gross R. Metabolic interdependence of obligate intracellular bacteria and their insect hosts. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2004;68:745–70.

-

Fiedler K, Kuhlmann F, Schlick-Steiner BC, Steiner FM, Gebauer G. Stable N-isotope signatures of central European ants - Assessing positions in a trophic gradient. Insectes Soc. 2007;54:393–402.

-

Seifert B. The ants of central and north Europe. Boxberg: Lutra; 2018.

-

Creighton WS, Snelling RR. Notes on the behavior of three species of Cardiocondyla in the United States (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). J. N. Y. Entomol. Soc. 1974;82:82–92.

-

Guariento E, Wanek W, Fiedler K. Consistent shift in nutritional ecology of ants reveals trophic flexibility across alpine tree-line ecotones. Ecol Entomol. 2021;46:1082–92.

-

Degnan PH, Lazarus AB, Brock CD, Wernegreen JJ. Host-symbiont stability and fast evolutionary rates in an ant-bacterium association: Cospeciation of Camponotus species and their endosymbionts, Candidatus Blochmannia. Syst Biol. 2004;53:95–110.

-

Degnan PH. Genome sequence of Blochmannia pennsylvanicus indicates parallel evolutionary trends among bacterial mutualists of insects. Genome Res. 2005;15:1023–33.

-

Gil R, Silva FJ, Zientz E, Delmotte F, Gonzalez-Candelas F, Latorre A, et al. The genome sequence of Blochmannia floridanus: Comparative analysis of reduced genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:9388–93.

-

Williams LE, Wernegreen JJ. Unprecedented loss of ammonia assimilation capability in a urease-encoding bacterial mutualist. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:687.

-

Williams LE, Wernegreen JJ. Sequence context of indel mutations and their effect on protein evolution in a bacterial endosymbiont. Genome Biol Evol. 2013;5:599–605.

-

McCutcheon JP, Von Dohlen CD. An interdependent metabolic patchwork in the nested symbiosis of mealybugs. Curr Biol. 2011;21:1366–72.

-

Patiño-Navarrete R, Moya A, Latorre A, Peretó J. Comparative genomics of Blattabacterium cuenoti: The frozen legacy of an ancient endosymbiont genome. Genome Biol Evol. 2013;5:351–61.

-

Sloan DB, Moran NA. Genome reduction and co-evolution between the primary and secondary bacterial symbionts of psyllids. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29:3781–92.

-

Santos-Garcia D, Mestre-Rincon N, Ouvrard D, Zchori-Fein E, Morin S. Portiera gets wild: Genome instability provides insights into the evolution of both whiteflies and their endosymbionts. Martinez-Romero E, editor. Genome Biol Evol. 2020;12:2107–24.

-

Tamas I. 50 million years of genomic stasis in endosymbiotic bacteria. Science. 2002;296:2376–9.

-

Sameshima S, Hasegawa E, Kitade O, Minaka N, Matsumoto T. Phylogenetic comparison of endosymbionts with their host ants based on molecular evidence. Zool Sci. 1999;16:993–1000.

-

Husnik F, McCutcheon JP. Repeated replacement of an intrabacterial symbiont in the tripartite nested mealybug symbiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E5416–24.

-

Monnin D, Jackson R, Kiers ET, Bunker M, Ellers J, Henry LM. Parallel evolution in the integration of a co-obligate aphid symbiosis. Curr Biol. 2020;30:1949–57.

-

Blochmann F. Über das Vorkommen bakterienähnlicher Gebilde in den Geweben und Eiern verschiedener Insekten. Zentbl Bakteriol. 1887;11:234–49.

-

Sauer C, Dudaczek D, Holldobler B, Gross R. Tissue localization of the endosymbiotic bacterium “Candidatus Blochmannia floridanus” in adults and larvae of the carpenter ant Camponotus floridanus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:4187–93.

-

Moran NA, Plague GR, Sandström JP, Wilcox JL. A genomic perspective on nutrient provisioning by bacterial symbionts of insects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:14543–8.

-

Manzano-Marín A, Oceguera-Figueroa A, Latorre A, Jiménez-García LF, Moya A. Solving a bloody mess: B-vitamin independentmetabolic convergence among gammaproteobacterial obligate endosymbionts from blood-feeding arthropods and the Leech Haementeria officinalis. Genome Biol Evol. 2015;7:2871–84.

-

Flydal MI, Martinez A. Phenylalanine hydroxylase: Function, structure, and regulation. IUBMB Life. 2013;65:341–9.

-

Simonet P, Gaget K, Parisot N, Duport G, Rey M, Febvay G, et al. Disruption of phenylalanine hydroxylase reduces adult lifespan and fecundity, and impairs embryonic development in parthenogenetic pea aphids. Sci Rep. 2016;6:34321.

-

Han Q, Phillips RS, Li J. Editorial: Aromatic amino acid metabolism. Front Mol Biosci. 2019;6:22.

-

Vavricka CJ, Christensen BM, Li J. Melanization in living organisms: a perspective of species evolution. Protein Cell. 2010;1:830–41.

-

Anbutsu H, Moriyama M, Nikoh N, Hosokawa T, Futahashi R, Tanahashi M, et al. Small genome symbiont underlies cuticle hardness in beetles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:E8382–91.

-

José de Souza D, Devers S, Lenoir A. Blochmannia endosymbionts and their host, the ant Camponotus fellah: Cuticular hydrocarbons and melanization. C R Biol. 2011;334:737–41.

-

Kiefer JST, Batsukh S, Bauer E, Hirota B, Weiss B, Wierz JC, et al. Inhibition of a nutritional endosymbiont by glyphosate abolishes mutualistic benefit on cuticle synthesis in Oryzaephilus surinamensis. Commun Biol. 2021;4:1–16.

-

Vigneron A, Masson F, Vallier A, Balmand S, Rey M, Vincent-Monégat C, et al. Insects recycle endosymbionts when the benefit is over. Curr Biol. 2014;24:2267–73.

-

Oakeson KF, Gil R, Clayton AL, Dunn DM, von Niederhausern AC, Hamil C, et al. Genome degeneration and adaptation in a nascent stage of symbiosis. Genome Biol Evol. 2014;6:76–93.

-

Engl T, Eberl N, Gorse C, Krüger T, Schmidt THP, Plarre R, et al. Ancient symbiosis confers desiccation resistance to stored grain pest beetles. Mol Ecol. 2018;27:2095–108.

-

Engl T, Schmidt THP, Kanyile SN, Klebsch D. Metabolic cost of a nutritional symbiont manifests in delayed reproduction in a grain pest beetle. Insects. 2020;11:1–15.

-

Duplais C, Sarou-Kanian V, Massiot D, Hassan A, Perrone B, Estevez Y, et al. Gut bacteria are essential for normal cuticle development in herbivorous turtle ants. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1–6.

-

Salem H, Kaltenpoth M. Beetle–bacterial symbioses: Endless forms most functional. Annu Rev Entomol. 2022;67:201–19.

-

Berasategui A, Moller AG, Weiss B, Beck CW, Bauchiero C, Read TD, et al. Symbiont genomic features and localization in the bean beetle Callosobruchus maculatus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2021;87:e0021221.

-

Kanyile SN, Engl T, Kaltenpoth M. Nutritional symbionts enhance structural defence against predation and fungal infection in a grain pest beetle. J Exp Biol. 2022;225:1–9.

-

Bisch G, Neuvonen M-M, Pierce NE, Russell JA, Koga R, Sanders JG, et al. Genome evolution of Bartonellaceae symbionts of ants at the opposite ends of the trophic scale. Martinez-Romero E, editor. Genome Biol Evol. 2018;10:1687–704.

-

Rubin BER, Kautz S, Wray BD, Moreau CS. Dietary specialization in mutualistic acacia-ants affects relative abundance but not identity of host-associated bacteria. Mol Ecol. 2019;28:900–16.

-

Brelsford A, Purcell J, Avril A, Tran Van P, Zhang J, Brütsch T, et al. An ancient and eroded social supergene is widespread across Formica ants. Curr Biol. 2020;30:304–11.e4.

-

Borowiec ML, Cover SP, Rabeling C. The evolution of social parasitism in Formica ants revealed by a global phylogeny. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021;118:e2026029118.

-

Moreau CS. Phylogeny of the ants: Diversification in the age of angiosperms. Science. 2006;312:101–4.

-

Heinze J. Life-history evolution in ants: the case of Cardiocondyla. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2017;284:20161406.

-

Fukatsu T, Ishikawa H. Soldier and male of an eusocial aphid Colophina arma lack endosymbiont: implications for physiological and evolutionary interaction between host and symbiont. J Insect Physiol. 1992;38:1033–42.

-

Davidson DW, Cook SC, Snelling RR, Chua TH. Explaining the abundance of ants in lowland tropical rainforest canopies. Science. 2003;300:969–72.

-

Hirota B, Okude G, Anbutsu H, Futahashi R, Moriyama M, Meng XY, et al. A novel, extremely elongated, and endocellular bacterial symbiont supports cuticle formation of a grain pest beetle. mBio. 2017;8:e01482–17.

-

Kuriwada T, Hosokawa T, Kumano N, Shiromoto K, Haraguchi D, Fukatsu T. Biological role of Nardonella endosymbiont in its weevil host. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:1–7.

-

Huger A. Experimentelle untersuchungen über die künstliche symbiontenelimination bei vorratsschädlingen: Rhizopertha Dominica F. (bostrychidae) und Oryzaephilus Surinamensis L. (Cucujidae). Z für Morphol und Ökologie der Tiere. 1956;44:626–701.

-

Mansour K. On the microorganism-free and the infected Clandra granaria L. Bull Soc R entomol Egypt. 1935;19:290–306.

-

Ün Ç, Schultner E, Manzano-Marín A, Flórez L V, Seifert B, Heinze J, et al. Cytoplasmic incompatibility between Old and New World populations of a tramp ant. Evolution (N Y). 2021;1775–91.

-

Douglas AE. The symbiotic habit. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press; 2010.

-

Ankrah NYD, Chouaia B, Douglas AE. The cost of metabolic interactions in symbioses between insects and bacteria with reduced genomes. mBio. 2018;9:1–15.

-

Nurk S, Bankevich A, Antipov D, Gurevich A, Korobeynikov A, Lapidus A, et al. Assembling genomes and mini-metagenomes from highly chimeric reads. In: Deng M, Jiang R, Sun F, Zhang X, editors. Research in Computational Molecular Biology. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2013. p. 158–70.

-

Seemann T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–9.

-

Caspi R, Foerster H, Fulcher CA, Kaipa P, Krummenacker M, Latendresse M, et al. The MetaCyc Database of metabolic pathways and enzymes and the BioCyc collection of pathway/genome databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:623–31.

-

Emms DM, Kelly S. OrthoFinder: solving fundamental biases in whole genome comparisons dramatically improves orthogroup inference accuracy. Genome Biol. 2015;16:1–14.

-

Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: Paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1–13.

-

Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57.

-

Ward PS, Blaimer BB, Fisher BL. A revised phylogenetic classification of the ant subfamily Formicinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), with resurrection of the genera Colobopsis and Dinomyrmex. Zootaxa. 2016;4072:343–57.

-

Husník F, Chrudimský T, Hypša V. Multiple origins of endosymbiosis within the Enterobacteriaceae (γ-Proteobacteria): Convergence of complex phylogenetic approaches. BMC Biol. 2011;9:1–18.

-

Lee MD, Ponty Y. GToTree: a user-friendly workflow for phylogenomics. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:4162–4.

-

Tanabe AS. Phylogears 2 v.2.0.x. 2008.

-

Lartillot N, Philippe H. Computing Bayes factors using thermodynamic integration. Syst Biol. 2006;55:195–207.

-

Lartillot N, Philippe H. A Bayesian mixture model for across-site heterogeneities in the amino-acid replacement process. Mol Biol Evol. 2004;21:1095–109.

-

Lartillot N, Brinkmann H, Philippe H. Suppression of long-branch attraction artefacts in the animal phylogeny using a site-heterogeneous model. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:1–14.

-

Lartillot N, Lepage T, Blanquart S. PhyloBayes 3: A Bayesian software package for phylogenetic reconstruction and molecular dating. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2286–8.

-

Rambaut A, Drummond AJ, Xie D, Baele G, Suchard MA. Posterior summarization in Bayesian phylogenetics using Tracer 1.7. Syst Biol. 2018;67:901–4.

-

Adeolu M, Alnajar S, Naushad S, Gupta RS. Genome-based phylogeny and taxonomy of the ‘Enterobacteriales’: Proposal for enterobacterales ord. nov. divided into the families Enterobacteriaceae, Erwiniaceae fam. nov., Pectobacteriaceae fam. nov., Yersiniaceae fam. nov., Hafniaceae fam. nov., Morgane. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2016;66:5575–99.

-

Charleston M. TreeMap 3b:a Java program for cophylogeny mapping. 2011.

-

Romiguier J, Rolland J, Morandin C, Keller L. Phylogenomics of palearctic Formica species suggests a single origin of temporary parasitism and gives insights to the evolutionary pathway toward slave-making behaviour. BMC Evol Biol. 2018;18:1–8.

-

Goropashnaya AV, Fedorov VB, Seifert B, Pamilo P. Phylogenetic relationships of Palaearctic Formica species (hymenoptera, Formicidae) based on mitochondrial cytochrome b sequences. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e41697.

-

Oettler J, Suefuji M, Heinze J. The evolution of alternative reproductive tactics in male Cardiocondyla ants. Evolution (N. Y). 2010;64:3310–7.

-

Heinze J, Seifert B, Zieschank V. Massacre of the innocents in Cardiocondyla thoracica: Manipulation by adult ant males incites workers to kill their immature rivals. Entomol Sci. 2016;19:239–44.

-

Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Walters WA, Berg-Lyons D, Lozupone CA, Turnbaugh PJ, et al. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:4516–22.

-

Epp LS, Boessenkool S, Bellemain EP, Haile J, Esposito A, Riaz T, et al. New environmental metabarcodes for analysing soil DNA: Potential for studying past and present ecosystems. Mol Ecol. 2012;21:1821–33.

-

Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB, et al. Introducing mothur: Open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:7537–41.

-

Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2460–1.

-

Edgar RC. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat Methods. 2013;10:996–8.

-

King T, Butcher S, Zalewski L. Apocrita - High performance computing cluster for Queen Mary University of London. Queen Mary Univ London, Tech Rep. 2017;1–2.

-

Rafiqi AM, Rajakumar A, Abouheif E. Origin and elaboration of a major evolutionary transition in individuality. Nature. 2020;585:239–44.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sabine Frohschammer, Sylvia Cremer, Tina Wanke, Masaki Suefuji, D. Ortius, K. Yamauchi, and Dominic Burns for providing ant samples. We would also like to thank Dr. David Alexander Harrap for consulting on appropriate latin usage conventions for the proposed new species and genus names.

Funding

This research utilised Queen Mary’s Apocrita HPC facility, supported by QMUL Research-IT [90]. This project was funded by L.M.H.’s NERC IRF (NE/M018016/1), and Marie Curie (H2020-MSCA-IF- 2017-796778-SYMOBLIGA).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

School of Biological and Behavioural Sciences, Queen Mary University of London, London, E1 4NS, UK

Raphaella Jackson, David Monnin, Patapios A. Patapiou, Gemma Golding, Yannick Wurm, Chloe K. Economou & Lee M. Henry

Department of Pathobiology and Population Sciences, Royal Veterinary College, Hatfield, AL9 7TA, UK

Patapios A. Patapiou

Ecology and Genetics Research Unit, University of Oulu, Oulu, 90014, Finland

Heikki Helanterä

Tvärminne Zoological Station, University of Helsinki, Hanko, Finland

Heikki Helanterä

Zoology/Evolutionary Biology, University of Regensburg, Regensburg, 93040, Germany

Jan Oettler & Jürgen Heinze

Alan Turing Institute, London, NW1 2DB, UK

Yannick Wurm

Department of Ecology and Evolution, University of Lausanne, 1015, Lausanne, Switzerland

Michel Chapuisat

Contributions

Designed research: RJ, DM, LMH. Performed research: RJ, DM, PAP, GG, CKE. Contributed new reagents/analytic tools/samples: HH, JO, JH, YW, MC. Analysed data: RJ, DM. Wrote the paper: RJ, DM, LMH.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Lee M. Henry.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Tables

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.