Ants, Bees, Genomes & Evolution @ Queen Mary University London

Published: 09 October 2012

Epigenetics: The Making of Ant Castes

Alexandra Chittka, Yannick Wurm, Lars Chittka

Current Biology, 2012, Vol. 22, Issue 19, PR835-R838

Summary

Social insects represent a unique model for how the same genome can give rise to entirely different phenotypes — soldiers, common labourers, and queens. New research on ants and honeybees points to DNA methylation as a crucial factor in determining the caste of a developing individual.

Main Text

Ants are an extraordinarily successful life form — their global numbers have been estimated as between one and ten million billion [1] — and surely part of this success is based on their division of labour. Only one or a small proportion of individuals of the colony, the queens, reproduce, while workers share the other duties which include constructing, maintaining and defending the nest, collecting food, and rearing the brood. Some ant species harbour special castes of particularly large workers, ‘soldiers’ or ‘majors’ (Figure 1), that preferentially play roles in colony defence, or for cutting up or carrying large objects, including prey. Morphology, physiology and behaviour thus differ profoundly between castes — a soldier, for example, can have 100 times the body mass of a ‘minor’ worker [1], and queens in some species live for decades whereas workers typically perish after a few months [2, 3]. Remarkably, however, each female embryo has the potential to become either queen, major, or minor worker — all can be moulded from the same genome. Environmental stimuli, such as the chemical components and amount of larval nutrition, pheromones, and temperature [1], set the developing embryo on one or the other trajectory towards its ultimate caste fate. While there are genetic differences in individuals’ responses to such environmental stimuli (for example in sensitivity thresholds to certain pheromones), in turn affecting the probability that an individual embryo is launched on a certain developmental trajectory [4], the genome of the female (diploid) ant embryo contains the potential to generate members of any non-male caste (males develop from haploid embryos).

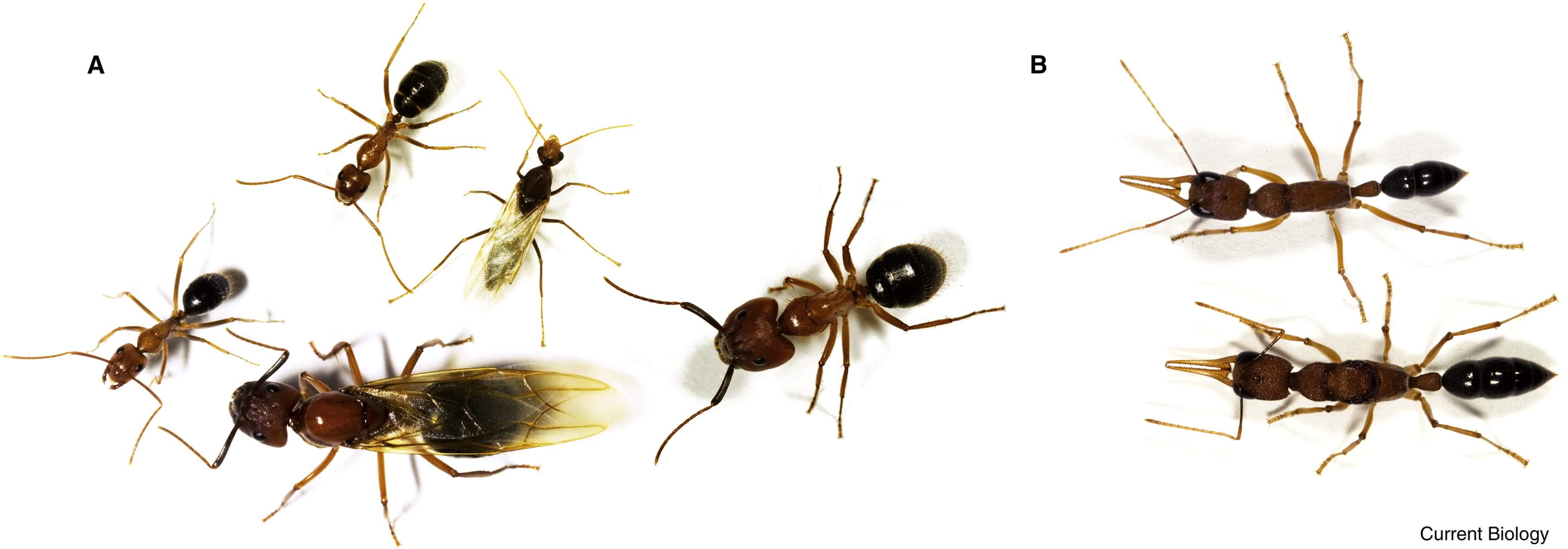

Figure 1 – Specialization and flexibility in ant castes.

Bonasio et al. [7] focussed on two ant species that differ in the flexibility of their reproductive division of labour. (A) Camponotus floridanus, a winged (virgin) queen (bottom, centre – the wings are shed after mating); a (winged) male (top, centre), a ‘major’ worker (soldier) on the right, and two minor workers (bottom left and top left). In this species, caste structure is rigid and if the queen dies, the colony, too, perishes. (B) Harpegnathos saltator, a worker (top) and queen (bottom). In this species, workers can turn into functional queens (gamergates) if the need arises. (Images by J. Liebig, with permission.)

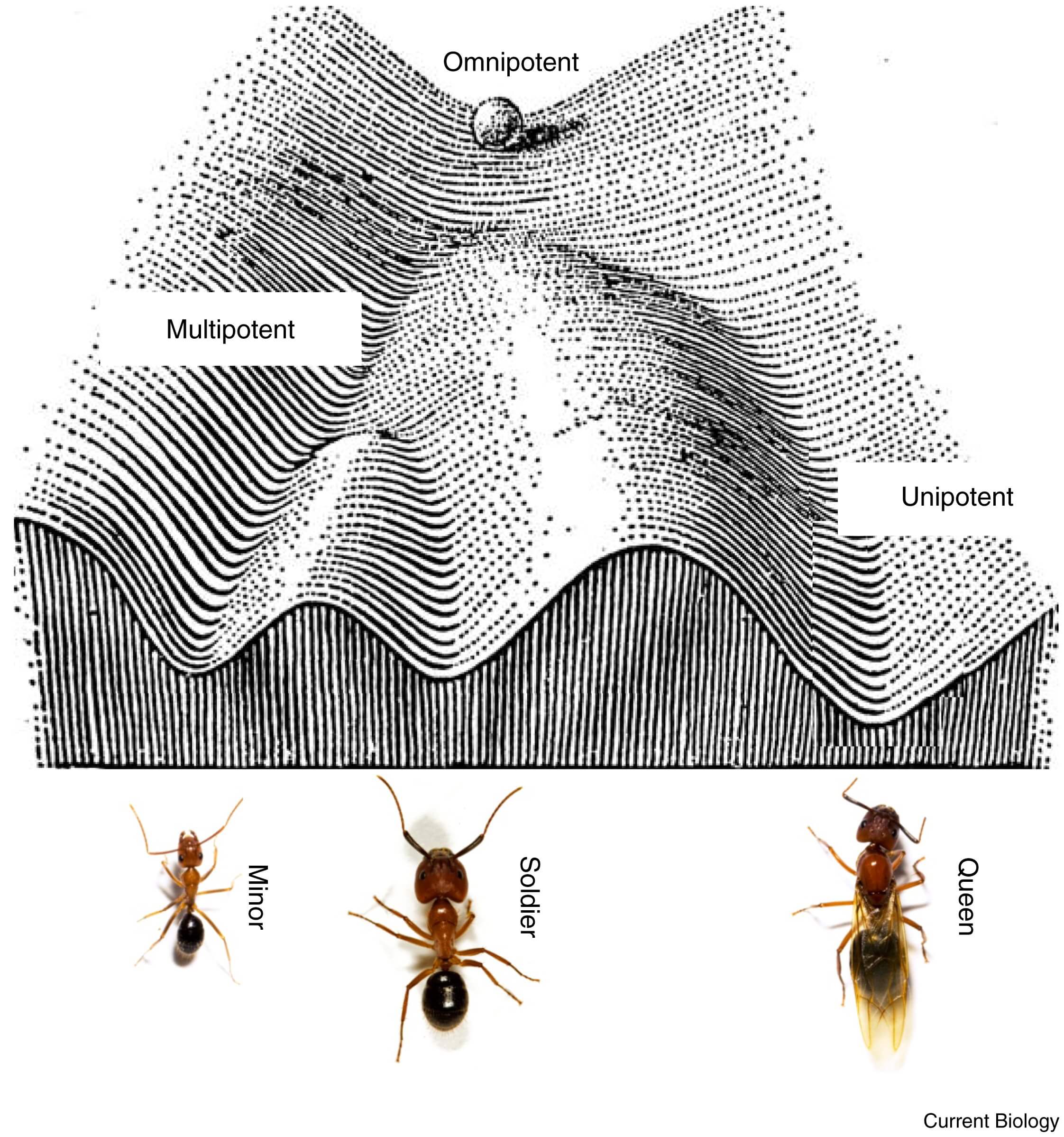

This means that the initiation and stability of development towards a caste must be mediated, to some extent, by epigenetic processes. Epigenetics refers to inherited (through cell divisions, not necessarily generations) changes in gene expression or phenotype not mediated by changes in DNA sequence. An obvious example is cellular differentiation in the development of multicellular organisms. Despite the enormous diversity in cell types in an animal (consider photoreceptors, hepatocytes, osteocytes, neurons, lymphocytes etc.) these cells are essentially clonal within an individual and all share the same genes, but in each cell type only a subset of genes is expressed. As the organism develops from totipotent stem cells, progressively more specialized cell types emerge in the embryo, each of which pass on certain traits to their daughter cells. These traits persist through cell division [5] in such a way that neural stem cells, for example, only ever give rise to cells of the neural lineage (but never osteocytes etc.). In the same way, caste differentiation in developing ant embryos is thought to be a step-by-step process, with discrete switches at certain points in time during development [1]. In ant embryonic development, the earliest decision point is typically thought to be the queen versus worker differentiation, and in many species there is a later branch point at which it is decided whether a worker turns into a major or minor (Figure 2).

Figure 2 – A Waddington landscape for ant caste determination.

Waddington's epigenetic landscape can be used as a metaphor for social insect caste determination (modified after [16]). Consider the developing embryo as a ball rolling down a valley. At first, the trajectory that the ball might ultimately take is open-ended — it is ‘omnipotent’. Further down the valley, the ball might encounter various branching points. Whether it takes the left or right branch depends, to some extent, on stochastic processes, as well as the precise local shape of the landscape (equivalent to certain genetic predispositions), or environmental influences. Slightly beyond a branch, the ball can still change direction based on a slight nudge from an environmental influence, and the same is thought to be possible in developing embryos of social insects. However, once the ball has rolled down a particular valley too far, the trajectory might be irreversible, and fate can then no longer be changed (for example, from queen to worker). Branching points further down the slope might be equivalent to the ‘soldier’ versus ‘common worker’ decision point found in some species of ants. (Images of ants by J. Liebig, with permission.)

One mechanism by which stable programmes of gene expression might be preserved through cell divisions to maintain a particular phenotype is DNA methylation — the covalent attachment of a methyl group to a cytosine nucleotide, typically in CpG dinucleotides. DNA methylation patterns differ between different cell types of multicellular organisms and methyl group ‘tags’ are retained through cell divisions with high fidelity (96%) [5]. This makes their involvement in determining and maintaining gene expression patterns in the cells of developing individuals likely. However, it is important to keep in mind that DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), the enzymes that catalyze DNA methylation, have no specificity for marking particular stretches of DNA [6] and are thus likely rather passive players which need to be recruited and targeted to specific DNA sites by transcription factors which recognise and bind specific DNA sequences when DNA methylation is first established.

In this issue of Current Biology, Bonasio et al. [7] have now obtained the entire ‘methylomes’ for several castes of two representative ant species, the Florida carpenter ant (Camponotus floridanus) and Jerdon’s jumping ant (Harpegnathos saltator). These two species differ profoundly in the rigidity of their caste structure (Figure 1). The castes of Camponotus are clearly defined in terms of behaviour and morphology, and once differentiated, members of one caste can never become members of another. Conversely, and perhaps similarly to the ancestral state of the ants, Harpegnathos retains considerable flexibility in its caste membership: workers and queens are morphologically similar, have similar life spans and indeed workers can become functional queens (‘gamergates’) if their colony has lost its queen [2].

What is a methylome? While it is straightforward to refer to an organism’s genome (since all its cells essentially contain the same DNA), the definition of a methylome (as part of ‘epigenome’) is trickier since a single animal might easily have thousands. There are at least as many epigenetic configurations as there are cell types in an animal, and indeed there are more since each cell will typically be able to adopt more than one epigenetic state [5]. Typically, the term methylome refers to the average number (or percentage) of DNA strands in which methylation is found at each genomic site across the many strands of DNA from cells of a particular tissue (or even whole individuals in the case of Bonasio et al. [7]).

Bonasio et al. [7] found that the most heavily methylated genes are likely to be constitutively expressed ‘housekeeping genes’ — their products serve essential functions in all cells of the body. These are often evolutionarily conserved, not just between ant species, and other Hymenoptera, but across animals [8]. In addition, the authors discovered clear differences in methylation between ant castes, although these are less pronounced in Harpegnathos than in Camponotus, consistent with the relative similarity of castes in the former and rigid caste differentiation in the latter. In agreement to what one might expect given the sequential embryonic differentiation decisions (first between reproductives and workers, then between majors and minors; Figure 2) in Camponotus, the methylation profiles of minors and majors are more similar to one another than either of these are to queens. Similarly, the worker-turned-reproductive-gamergates in Harpegnathos retained a DNA methylation profile which was more similar to the workers than to the queen.

As in honeybees [9], the bulk of DNA methylation in these ants was in the exons of transcribed genes, with the levels of methylation correlating positively with gene expression. However, the similarities in methylomes did not translate directly into similarities in transcriptomes. For example, transcriptomes of Harpegnathos gamergates are more similar to transcriptomes of queens than of normal workers. There are likely at least three reasons for the lack of a simple picture of ‘queen genes’ vs ‘worker genes’ switched on or off according to patterns of differential methylation. First, differences in the relative sizes of organs or body parts (allometry) confound whole-body comparisons between castes. Second, while all cells in the body are equally represented in methylome comparisons, large gene expression differences in a few tissues (e.g. the reproductive organs) can mask more subtle differences in the rest of the body. In the future, it will be useful to establish the methylome of particular tissues of the various ant castes, since valuable information might be lost through whole-organism ‘averaging’.

Finally, genes completely lacking methylation showed greater gene expression differences between castes than genes methylated in at least some samples. This indicates that profound changes in behaviour and physiology can be affected without drastic changes in DNA methylation [10].

One convenient way to turn a single segment of DNA into more than one gene product is by alternative splicing, where segments of mRNA are connected in more than one way to encode for more than a single protein. In social insect caste determination one might therefore expect that some genes could be differentially channelled to making two (or more) different caste-specific gene products. Indeed, in honeybees, a correlation exists between caste, alternative splicing and DNA methylation, where the position of methyl tags on DNA might determine which exons are included in the spliced transcript [11]. Bonasio et al. [7] confirm a correlation between DNA methylation and splicing for the two ant species under investigation. More studies will be necessary to determine the exact usage of alternative splice sites and the possible role of differential splicing in determining the developmental pathways followed by the different ant castes.

Several differentially methylated genes associated with the queen–worker dimorphism are conserved between the two species, suggesting their involvement in mediating caste determination in the common ancestor more than 100 million years ago. About half of these could be classified into three functional categories, reproductive biology, noncoding RNA metabolism, and telomere maintenance. Furthermore, the authors found examples of caste-specific, allele-specific methylation that correlated with allele-specific expression. In Camponotus, one of these differentially methylated alleles codes for a zinc finger protein which in other animals likely plays roles in reproduction and gamete generation. Given the importance of DNA demethylation and remethylation in reproductive cells in other animals, e.g., the primordial germ cells in mammals, and the involvement of noncoding RNA in the control of epigenetic reprogramming of the primordial germ cells [12], this might indicate that one of the more important functions of differential DNA methylation in the ant castes is to contribute to the proper function of germ cell biology.

The link between caste-specific differential methylation and maintenance of telomeres (chromosome ends) is intriguing because of its potential links to the biology of ageing. Telomeres shorten with each somatic cell division, and once they are shortened to a threshold level, no further cell divisions are possible [3]. The lifespan of ant queens exceeds that of workers by an order of magnitude or more, but in at least one other ant species no worker–queen differences in telomere length were detected [3]. However, a different function of telomerase maintenance might also be more important in queens than in workers, i.e. the avoidance of telomere shortening in germ cells, a key factor for their potential to reproduce indefinitely. Equally intriguingly, the genes coding for small non-coding RNAs, known as piRNAs, were also found to be differentially methylated in queens and workers of both species. These piRNAs are instrumental for targeting DNA methylation to the transposable elements specifically in the germ cells during their developmental re-programming, and are thus another key factor in granting germline cells infinite numbers of division.

Bonasio et al. somewhat pessimistically comment that the “origin and ultimate function of …[gene body] methylation, which is found in all organisms that express DNMTs [DNA methyl transferases – the enzymes that mediate the attachment of methyl tags to DNA]… remains unknown.” It is clear that much work remains to be done to understand the functional link between methylation patterns and gene expression in ants and other animals. Unlike in honeybees [9, 13, 14], we do not yet understand the environmental signals that nudge the developing female ant embryo onto one or the other career path. This in turn makes it more difficult to decipher the molecular pathways by which such signals are converted into epigenetic reprogramming of the embryo. This and the fact that it is not yet possible to experimentally manipulate methylation patterns at specific DNA sites make the establishment of functional links challenging. Nonetheless correlative studies such as those presented here, in conjunction with experimental manipulations that at least affect overall levels of DNA methylation during development (e.g., [15]) should pave the way to a more comprehensive understanding of epigenetics in the determination of an individual’s caste specialisation.

References

-

Hölldobler B. Wilson E.O. The Superorganism. Norton, New York, London 2009

-

Gadau J. Helmkampf M. Nygaard S. Roux J. Simola D.F. Smith C.R. Suen G. Wurm Y. Smith C.D. The genomic impact of 100 million years of social evolution in seven ant species. Trends Genet. 2012; 28: 14-21

-

Jemielity S. Kimura M. Parker K.M. Parker J.D. Cao X.J. Aviv A. Keller L. Short telomeres in short-lived males: what are the molecular and evolutionary causes?. Aging Cell. 2007; 6: 225-233

-

Schwander T. Lo N. Beekman M. Oldroyd B.P. Keller L. Nature versus nurture in social insect caste differentiation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010; 25: 275-282

-

Bird A. Perceptions of epigenetics. Nature. 2007; 447: 396-398

-

Ptashne M. On the use of the word ‘epigenetic’. Curr. Biol. 2007; 17: R233-R236

-

Bonasio R. Li Q. Lian J. Mutti N.S. Jin L. Zhao H. Zhang P. Wen P. Xiang H. Ding Y. et al. Genome-wide and caste-specific DNA methylomes of the ants Camponotus floridanus and Harpegnathos saltator. Curr. Biol. 2012; 22: 1755-1764

-

Zemach A. McDaniel I.E. Silva P. Zilberman D. Genome-wide evolutionary analysis of eukaryotic DNA methylation. Science. 2010; 328: 916-919

-

Lyko F. Foret S. Kucharski R. Wolf S. Falckenhayn C. Maleszka R. The honeybee epigenomes: differential methylation of brain DNA in queens and workers. PLoS Biol. 2010; 8: e1000506

-

Ptashne M. Binding reactions: epigenetic switches, signal transduction and cancer. Curr. Biol. 2009; 19: R233-R236

-

Foret S. Kucharski R. Pellegrini M. Feng S.H. Jacobsen S.E. Robinson G.E. Maleszka R. DNA methylation dynamics, metabolic fluxes, gene splicing, and alternative phenotypes in honey bees. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012; 109: 4968-4973

-

Law J.A. Jacobsen S.E. Establishing, maintaining and modifying DNA methylation patterns in plants and animals. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010; 11: 204-220

-

Kamakura M. Royalactin induces queen differentiation in honeybees. Nature. 2011; 473: 478-483

-

Chittka A. Chittka L. Epigenetics of royalty. PLoS Biol. 2010; 8: e1000532

-

Kucharski R. Maleszka J. Foret S. Maleszka R. Nutritional control of reproductive status in honeybees via DNA methylation. Science. 2008; 319: 1827-1830

-

Waddington C.H. The Strategy of the Genes; a Discussion of Some Aspects of Theoretical Biology. Allen and Unwin, London 1957

Article Info

Identification

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2012.07.045

Copyright

© 2012 Elsevier Ltd. Published by Elsevier Inc.

User License

ScienceDirect

Access this article on ScienceDirect