Ants, Bees, Genomes & Evolution @ Queen Mary University London

Published: 06 October 2011

The genomic impact of 100 million years of social evolution in seven ant species

Jürgen Gadau, Martin Helmkampf, Sanne Nygaard, Julien Roux, Daniel F. Simola, Chris R. Smith, Garret Suen, Yannick Wurm, Christopher D. Smith

Trends in Genetics, 2011, 28:14-21

Ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) represent one of the most successful eusocial taxa in terms of both their geographic distribution and species number. The publication of seven ant genomes within the past year was a quantum leap for socio- and ant genomics. The diversity of social organization in ants makes them excellent model organisms to study the evolution of social systems. Comparing the ant genomes with those of the honeybee, a lineage that evolved eusociality independently from ants, and solitary insects suggests that there are significant differences in key aspects of genome organization between social and solitary insects, as well as among ant species. Altogether, these seven ant genomes open exciting new research avenues and opportunities for understanding the genetic basis and regulation of social species, and adaptive complex systems in general.

Glossary

Caste

a subset of individuals in an insect colony that are characterized either behaviorally or morphologically.

Environmental caste determination (ECD)

the differentiation between queens and worker castes is determined by environmental factors, such as exposure to hormones, temperature, or alternate food sources. This is thought to be the main mechanism of caste determination across eusocial species.

Epigenetics

the study of heritable molecular differences resulting in a measurable phenotype that result from DNA methylation or chromatin modification, such as histone methylation, rather than alterations in the DNA sequence itself.

Eusociality

a form of social organization found in all ants (as well as some other insects, crustaceans and vertebrates) that is typified by a reproductive division of labor (i.e. queens and workers), overlapping generations and cooperative care of young.

Gamergate

in ant species, such as Harpegnathos saltator, a worker ant may mate and become fully reproductively active (i.e. queen like); that is, it can produce female and male offspring. Such a reproductive worker is called a gamergate.

Genetic caste determination (GCD)

reproductive caste is determined by intrinsic (genetic) factors acting upstream of environmental differences. For example, in some harvester ants, when queens of a lineage mate with males of the same lineage, a reproductive queen is produced. When queens mate with males of another lineage, workers are produced. Without mating occurring between both lineages, a colony cannot produce both workers and new queens.

Haplodiploid sex determination

a sex-determination system where unfertilized, haploid eggs develop into fertile males and diploid, fertilized eggs develop into females. One consequence of this system is that males normally have no father and cannot give rise to sons. Hymenoptera have a haplodiploid sex-determination system.

Hymenoptera

a large order of insects that have four transparent wings; it includes the bees, wasps, ants and sawflies. Females often have a sting.

Monandry

a pattern of mating in which a female animal mates with only one male.

Monogyny

in social insects, this refers to a social organization where there is a single reproductive female per colony (in contrast to the mating system bearing the same name).

Monomorphic

in social insects, this refers to workers that have the same overall body size, mass and morphology.

Polyandry

a pattern of mating in which a female animal mates with more than one male.

Polygyny

in social insects, this refers to a social organization where there are multiple reproductive females per colony (in contrast to the mating system bearing the same name).

Sociogenesis

the origin of social organization that derives from past interaction experiences.

Trophallaxis

transfer of liquid food between members of a social insect colony. The liquid food that is transferred has typically been stored in the crop or proventriculus of workers.

Unicoloniality

a social structure of ants in which the workers can move freely between different nests and do not show aggression toward non-nest mate workers, often because genetic variation is sufficiently low that individuals cannot distinguish ‘foreign’ colonies from their own.

Ant genomes: tools to study biological and social complexity

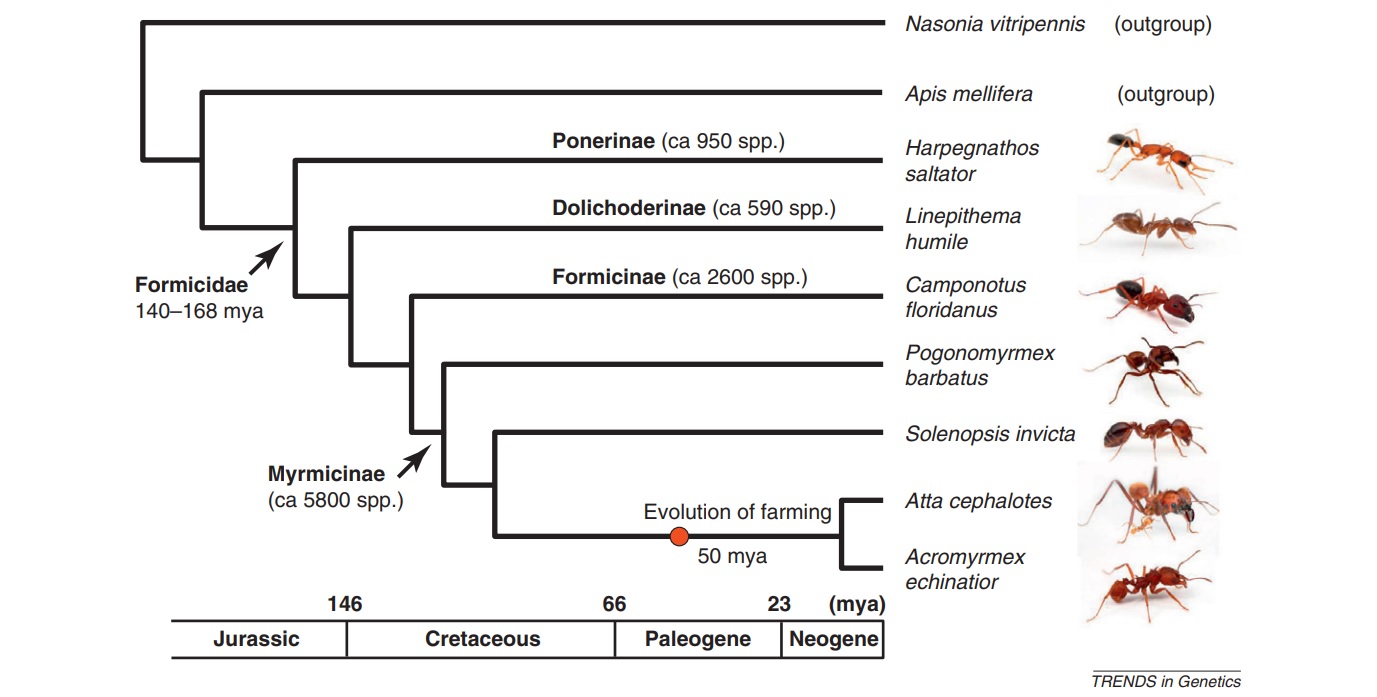

Ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae; see Glossary) comprise a dominant component of most terrestrial habitats. The more than 14000 described species (https://www.antweb.org/) show an enormous diversity in life-history features, ecological and behavioral adaptations and social organization, and are a prime example of a complex adaptive system [1–5]. Current evidence suggests that the last common ancestor of the ants lived during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, 140–168 million years ago (mya) and was already eusocial [6–9] (Figure 1). Hence, the seven ant species whose genomes have recently been published, represent a single origin of eusociality. However, within the ant lineage, there are independent origins of different types of social organization, making ants fertile ground to study the molecular mechanisms underlying the evolution of behavioral diversity [1, 10, 11]. Ant genomic data facilitate comparisons that permit a first evaluation of the ‘sociogenome’ hypothesis, initially proposed for honeybees (see below) [12–14].

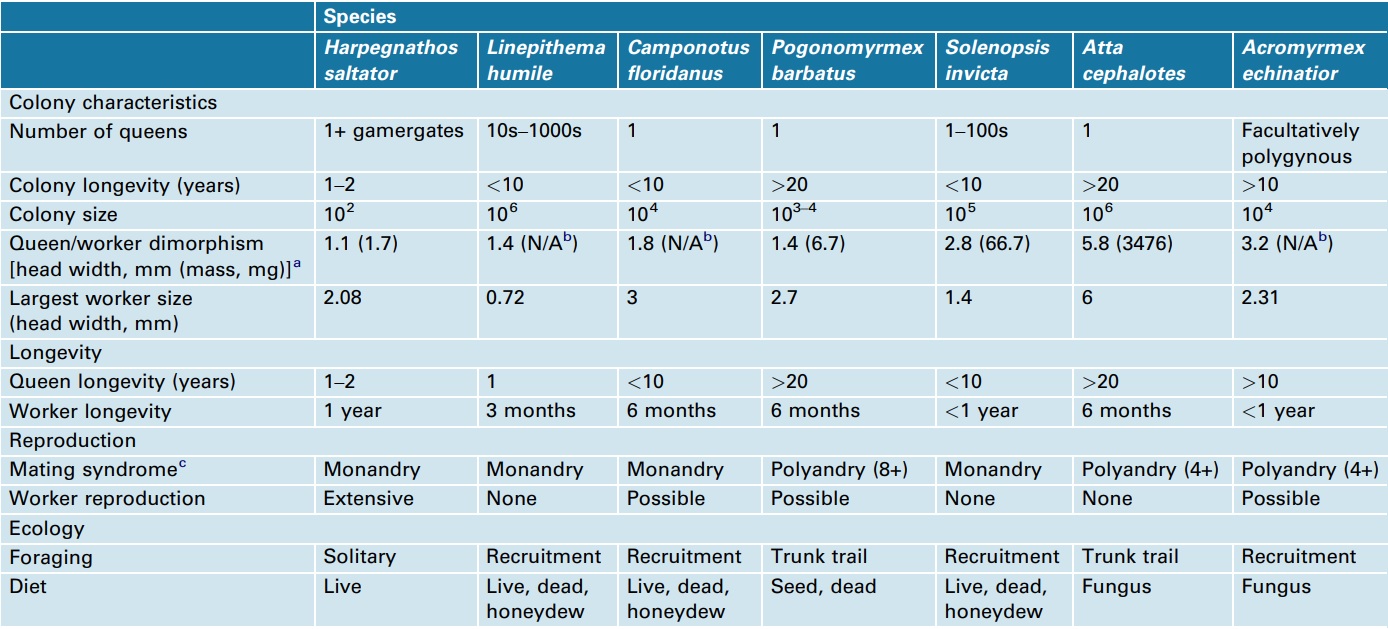

The first ant genomes sequenced were those of Jerdon’s jumping ant (Harpegnathos saltator) and the Florida carpenter ant (Camponotus floridanus), chosen because of their contrasting social structures (Figure 1) [15]. During early 2011, five more ant genomes were published: the globally invasive Argentine ant (Linepithema humile) [16], the red imported fire ant (Solenopsis invicta) [17], two leafcutter ant species (Atta cephalotes and Acromyrmex echinatior) [18, 19] and the red harvester ant, a desert ant that has both environmental and genetic caste determination (Pogonomyrmex barbatus) (Box 1) [20]. These seven species reflect a range of social structures, life-history traits and habitats, refined over approximately 100 million years of social evolution (Figure 1, Boxes 2 and 3), making it possible to study how these traits affect the composition, conservation and divergence of their genomes. Note that the Ponerinae, represented by H. saltator, branched out approximately 100 mya [7] and represent the oldest split within the seven sequenced ant species. Table 1 gives an overview of the evolutionarily important colony and lifehistory characteristics of the seven sequenced ant species, which can potentially be used as cofactors in a comparative analysis. Because eusociality is a shared, derived character for all ants, one would expect that they share the particular genetic and epigenetic regulatory architecture required to maintain eusociality. Alternatively, 100 million years of social evolution might be enough time to develop new and lineage-specific regulatory mechanisms, owing to the evolution of new forms of social organization (Box 3), such as was found in the wing regulatory networks in ants [21].

Genomic and genetic features of the seven sequenced ant species

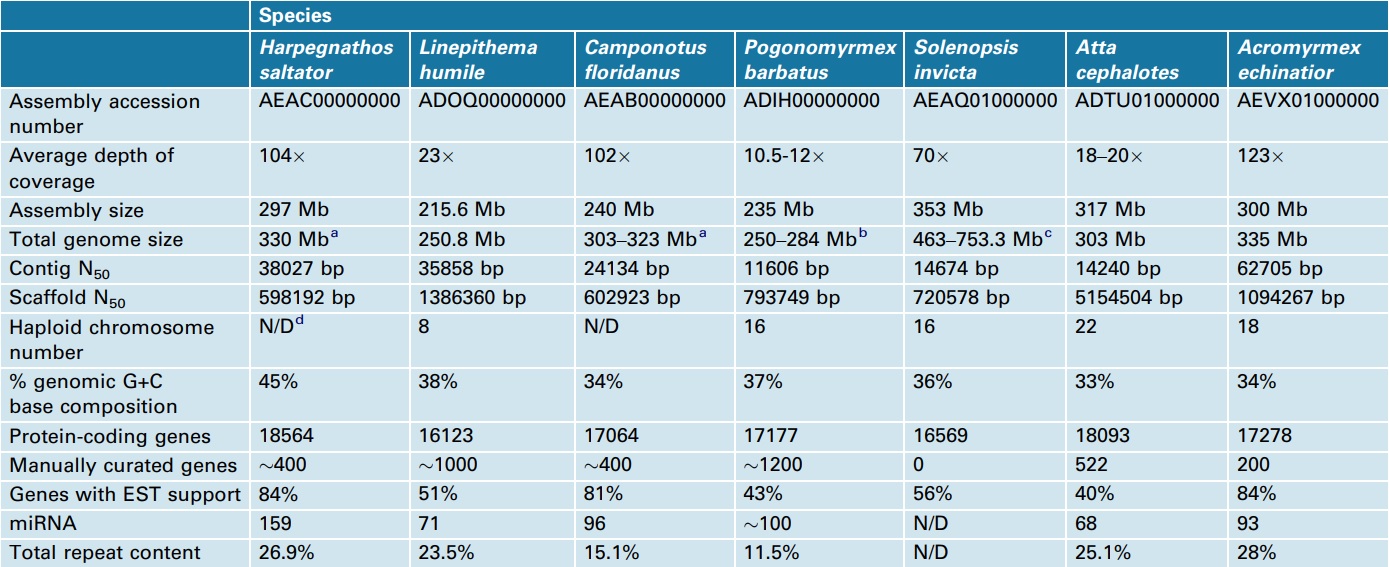

The use of different sequencing technologies and depth of coverage across the sequenced ant species (10.5–123) has yielded genome assemblies with a ten-fold range of median scaffold sizes (N50 from 598 kb to 5154 kb; Table 2). The overall size of these genomes ranges from 250 Mb to 753 Mb, and most of the variation in genome size is attributable to differences in repetitive element content (Table 2). Solenopsis invicta is the largest ant genome sequenced (353 Mb assembled) [17] and, although no genome-wide repeat analysis was completed, previous studies suggest that 64% of the genome is repetitive, with a large fraction being foldback transposable elements that possess long inverted repeats [22].

Figure 1

Phylogenetic relationship of the seven sequenced ant species and the two other sequenced hymenopteran taxa (outgroups). The phylogenetic relationship and timescale are based on Brady et al. [6] and Moreau et al. [7]; none of which are valid for the two outgroups (Apis mellifera and Nasonia vitripennis). As all the ants, the honeybee A. mellifera belongs to the aculeate Hymenoptera and, therefore, is more closely related to the ants than is N. vitripennis, a parasitoid wasp in the species-rich superfamily Chalcidoidea. Geologic timescale is shown for reference. Ant photos produced, with permission, from Alexander Wild (http://myrmecos.net/). Abbreviation: mya, million years ago.

Box 1 – Variations in ant division of labor and its regulation.

Reproductive division of labor can be characterized by varying levels of morphological, physiological and behavioral specialization. The sequenced ant species represent a continuum of female (queen and worker) caste specialization. For example, in Harpegnathos saltator, there is little difference between queens and workers, whereas Atta cephalotes queens are many times the size of workers, live decades longer and are specialized for a reproductive role in the colony. The other species fit somewhere between these two extremes. In Solenopsis invicta, variation in queen number is linked to a single genetic locus (Gp-9), where some colonies have a single queen and other colonies can harbor hundreds of queens [55–57].

As with the reproductive division of labor, workers can also be specialized for tasks within colonies [58]. In approximately half of the seven sequenced species, workers are monomorphic and switch tasks with age (typically transitioning away from nest tasks, such as brood care, toward exterior tasks, such as foraging). When present, morphological variation among workers can be continuous (e.g. S. invicta), where there are no gaps in size between the smallest and largest workers [59, 60], or it can be discrete (e.g. A. cephalotes and Camponotus floridanus), such as the occurrence of a defensive soldier caste [61].

A wide range of factors controls the basis for the production of different castes. As a developmental process, the roles of genes, nutrition, hormones and contacts with nest mates can interact to produce variation in the adult phenotype, as evidenced by the great variation within and among ant species [62]. Recent studies suggest that the roles of genetics and the environment in caste determination vary among species [14, 48, 62]. Much of this variability is reflected in the genomes of the sequenced ants: at one extreme, queens and workers of Pogonomyrmex barbatus differ genetically, where workers result from inter-lineage hybrids, whereas queens are produced from within-lineage matings) [63]. The role of genotypic differences in caste determination is less clear in most of the other sequenced ants. It is thought that different castes result from nutritional differences [64] that then trigger epigenetic or hormonal differences in larval development. However recent data suggest that there are also genetic components biasing caste differentiation [65–67]. For example, Acromyrmex echinatior represents a scenario where genetic and environmental factors both contribute to whether individuals develop as workers (small or large) or queens [68].

Other ant species have lineage-specific expansions of specific transposable element (TE) families, such as the Mariner elements in H. saltator [15]. Prior to the sequencing of the seven ant genomes, only two hymenopteran species, the honeybee (Apis mellifera) and the parasitoid jewel wasp (Nasonia vitripennis), had been sequenced, and both differ significantly in TE content (i.e. honeybees have very few TEs) [12, 23]. It had been speculated that the paucity of mobile elements in the honeybee (approximately 6% of the genome) is the result of ‘social hygienic behaviors’, such as the removal of deceased or diseased individuals, reciprocal cleaning of nest mates and so on, which would reduce the exposure to novel TE elements from the environment. However, ant genomes contain 11–28% repetitive elements (Table 2), similar to other solitary insects, including N. vitripennis [23]. Hence, eusociality and social hygienic behavior, which is also widespread in ants, is no protection against the proliferation of mobile elements.

Box 2 – Variations in colony life cycles.

The major functional evolutionary unit of ants is the colony, in which all individuals live through multiple annual cycles and develop in a systematic fashion, similar to a unitary organism (sociogenesis) [69]. One major difference among ants is whether the colony develops from independent colony formation with a single queen (monogyny) or multiple queens (polygyny), or from queens budding from a parent colony with a contingent of workers (dependent colony founding). The mode of colony development has major repercussions, such as the critical size of colonies to begin to reproduce, the trade off between producing many small or few large queens and/or males, and the environments in which they are most adaptive; for example, dependent colony foundation may be a more successful strategy in a saturated population [1].

Of the seven ant species with sequenced genomes, five found colonies from single queens (independent colony founding), Linepithema humile reproduces by fission (dependent colony founding), and Solenopsis invicta runs the gamut, founding colonies with single or multiple queens, and exhibiting both dependent and independent colony founding [55, 56, 59]. Colonies mature when they transition from producing only workers (growth) to producing new queens and males (reproduction) in annual cycles. If the queen dies, so does the colony because queenless workers are unable to mate or complete regression of ovaries. However, in some species, the workers may be able to mate and reproduce (e.g. Harpegnathos saltator), or at least produce males (unfertilized eggs become males owing to haplodiploid sex determination; e.g. Camponotus floridanus). Queens, and hence colonies, may live for several decades (e.g. Pogonomyrmex barbatus and Atta cephalotes), many years (e.g. C. floridanus), for only few years (e.g. H. saltator), or only for a single year (e.g. L. humile). In the case of L. humile and the multiple-queen form of S. invicta, colony structure and the presence of hundreds of breeding queens allow colony persistence for many years.

Box 3 – Variations in ant social organization.

Variations in colony life history and division of labor lead to differences in social structure and organization. Ant life cycles and division of labor are evolutionarily labile, such that there are many instances of independent origins of social structure and organization across the ant tree of life [1]. The presumed ancestral condition in ants is a society where there is little variation in reproductive potential among individuals, but societies become structured by dominance hierarchies, which then produce reproductive and behavioral division of labor [1, 2]. Of the sequenced ants, Harpegnathos saltator most resembles this condition. The other six ant species all form colonies with a more stringent reproductive division of labor, but vary in the number of queens per colony. Colonies of Atta cephalotes, Camponotus floridanus and Pogonomyrmex barbatus are headed by single queens, Acromyrmex echinatior is facultatively polygynous, whereas Linepithema humile colonies contain hundreds of breeding queens. In Solenopsis invicta, the presence of one or multiple reproductive queens is associated with allelic variation at a single Mendelian factor marked by the gene Gp9 [55–57, 60]. Multiple-queen colonies are characterized by limited queen dispersal, and colonies can reproduce by fission, which is often incomplete, as workers can travel between the parent and offspring colonies. This can result in a phenomenon called ‘unicoloniality’, where colonies lack aggression (via an inability to recognize nest mates) and territoriality, and in turn can result in very high colony densities [70, 71]. The invasiveness of both L. humile and S. invicta has increased owing to unicoloniality, as only a portion of a colony needs to be transferred to a new habitat for successful establishment. Once established, colony density can lead to greater ecological impact and exclusion of native species [72–74].

The seven sequenced ant species, in addition to variation in social organization, have evolved profound life-history differences, from agriculturalists that farm a fungus (A. cephalotes and A. echinatior), to seed harvesters that store seeds in underground vaults (P. barbatus), to obligate predators (H. saltator) and generalists (C. floridanus, S. invicta and L. humile) that prey on live animals, tend homopterans for honeydew, and scavenge seeds and dead organisms. Each of these syndromes, coupled with the habitat occupied by the colony (tropical forests, deserts, etc.) and its permanency (i.e. frequency of disturbance, longevity of the nest as a resource, etc.) correspond to adaptive variation in division of labor and social organization.

Table 1 – Comparison of biological differences among the sequenced ant species.

aLargest queen head width (or dry mass) divided by the smallest worker head width (or dry mass).

bN/A, not available.

cNumber of mates if value is greater than 1.

Table 2 – Comparison of ant genomes.

aAs determined by qPCR [15].

bBased on size estimations of related Pogonomyrmex spp. [75].

cGenome size estimates reviewed in [17].

dN/D, not determined.

In contrast to most other sequenced holometabolous insects [flies (Drosophila melanogaster), beetles (Tribolium castaneum) and moths (Bombyx mori)], complete DNA methylation gene sets have been described for all ant species, and DNA methylation appears widespread across both social and solitary Hymenoptera [24]. Over evolutionary time, methylated cytosine residues can mutate to thymine, which leads to adenine residues being incorporated into daughter strands, thus driving a trend toward AT-rich DNA [25]. Therefore, relative AT bias in ants and bees may be the result of a long history of DNA methylation activity linked to the regulation of social traits, such as division of labor and caste determination [26, 27]. Previous evidence from the honeybee (33% GC) and Nasonia (41% GC) genomes suggested that AT richness correlates with eusocial organization. However, ant genomes exhibit a wide range of GC composition (33–45%, Table 2), indicating that eusociality is not necessarily correlated with ATrich genomes.

Given that H. saltator (45%) has the least AT-biased genome, similar to Nasonia (44%), and is the sister taxon to the other sequenced ants, it is possible that the observed AT bias in the Myrmicinae and Dolochoderinae is a consequence of an increase in the use of DNA methylation in the these two lineages, perhaps even coupled with the evolution of more complex social organization. Alternatively, it is also possible that AT bias has been lost in Harpegnathos and that AT bias is an ancestral character for all ants and bees. An experimental comparison of the frequency of DNA methylation in the genomes of H. saltator and C. floridanus has shown that the less AT-biased genome is also less methylated [15] and that higher frequencies of DNA methylation are also correlated with more complex social organization in Camponotus. It would be an amazing evolutionary convergence if the use of DNA methylation has been co-opted by honeybees and ants independently to regulate social organization, or if an increase in DNA methylation is causally linked to an increase in social complexity between different ant lineages.

The predicted gene content for each of the ant species (16123–18564 genes, Table 2) is in line with the number of genes observed in other insects, including D. melanogaster (15209 [28]), N. vitripennis (17269 [23]) and T. castaneum (16404 [29]), but is somewhat more than the approximately 10000 genes predicted for the honeybee [12]. However, current re-annotation of the honeybee genome promises to increase the gene count for the honeybee (Christine Elsik, personal communication). Several of the analyzed ant genomes reported genes and domains that appear to be enriched relative to other Hymenoptera and insect genomes. Given that ants predominantly communicate using chemical signals, it was expected that their genomes would contain an expanded gene set compared with solitary insects.

Genes annotated with Gene Ontology [30] terms related to sensory perception, odorant binding, peptidase activity, lipid metabolic processes and G-protein coupled receptor activity were significantly enriched in several ants (e.g. L. humile and P. barbatus [16, 20]). Overall, chemical communication seems to play a more important role in ant societies compared with honeybee colonies, leading to a significant expansion of gene families involved in communication. Indeed, among all the insects studied, ants have some of the largest identified repertoires of odorant receptors (ORs; e.g. P. barbatus n = 344 and L. humile n = 367), ionotropic receptors (IRs; e.g. P. barbatus n = 24 and L. humile n = 32), and gustatory receptors (GRs; e.g. P. barbatus n = 73 and L. humile n = 116) [16, 20]. Honeybees, however, have a very low number of GRS, whereas the set of N. vitripennis seems in line with other insects (n = 10 and n = 58, respectively); both have only ten annotated IRs. Ants also show lineage-specific expansions of desaturase genes, which are probably responsible for synthesizing a more varied mixture of cuticular hydrocarbons, which are important for social insect-specific tasks, such as colony recognition and queen signaling [31, 32]. Cytochrome p450 genes have also expanded independently in several ant lineages, possibly reflecting species-specific needs for detoxifying specific food sources. These have greatly expanded in L. humile, P. barbatus and C. floridanus, which have more generalist diets [15, 16, 20]. Interestingly, this gene family has contracted in the two leaf-cutter ants (A. cephalotes and A. echinatior), perhaps because of a reduced need to detoxify farmed food sources [18, 19].

The gene encoding vitellogenin, a storage protein essential for egg production in insects [33], was duplicated in ancestors of S. invicta and shows subsequent sub-functionalization between queens and workers (i.e. all copies are differentially expressed in queens and workers) [17]. This is intriguing because the single honeybee gene vitellogenin regulates both life span [31, 32] and division of labor, traits that differ significantly between workers and queens [34–37]. If vitellogenin serves the same or similar function in ants, the proximate regulatory mechanisms would be fundamentally different between ants and bees; that is, ants would have caste-specific vitellogenin copies, whereas honeybee castes would differ in the expression pattern of their single vitellogenin.

All ant genomes, as well as that of the honeybee, have a reduced number of innate immunity genes compared with solitary insects [38]. Increased social hygienic behaviors in social insects, such as removal of deceased or diseased individuals and mutual grooming, hypothesized to reduce the need for a huge innate immunity arsenal [12]. Nasonia vitripennis, the closest sequenced relative to eusocial Hymenoptera, has a broader complement of innate genes, similar to other solitary insects [23], further supporting the hypothesis that eusocial organization and social behavior, in particular social hygienic behavior, is the driving force in the reduction of innate immune genes.

A common ancestor of A. cephalotes and A. echinatior began farming fungus 50 mya ago (Figure 1). This ecological relationship has since evolved into an obligate mutualistic symbiosis. Both leaf-cutter ant genomes show a loss of biosynthetic genes for arginine, which was not observed in any other ant species [18, 19]. Presumably, this deficiency reflects the fact that leaf-cutter ants obtain arginine through gardening of their cultivated fungus, a dependence that may have reinforced the symbiosis. Hence, diet changes owing to the evolution of agriculture in ants have left their mark on the genome, comparable with genetic changes associated with the evolution of cattle farming and adult lactose tolerance in humans.

Epigenetic control of caste determination

DNA methylation and histone modifications contribute to gene expression regulation and can be stably transmitted between cell division events [39]. Unlike genetic information, which changes slowly over the course of multiple generations, such epigenetic information can change quickly within an individual in response to changing environmental conditions (e.g. temperature, diet, and stress). Although an individual is only endowed with one nuclear genome, it can have multiple epigenomes that change through development and vary across cell types [40]. These features make epigenetic mechanisms prime candidates for the regulation of division of labor, where individuals may change tasks many times over their lifetime. The complexity of social insect behavior and caste development, coupled with the relative simplicity of their genomes and social structures (e.g. compared with primates), make these insects ideal systems to study how epigenetic mechanisms regulate social organization and behavior [41].

DNA methylation has been demonstrated to be an important mechanism used by honeybees to direct the expression of worker and queen caste-specific programs [26, 42, 43]. Given that DNA methylation of the germ line leaves a distinct genomic signature of CpG dinucleotide depletion [25, 43, 44], this signature has been used to assess the presence and genomic location of methylation in ant genomes. Methylated CpGs have a higher mutation rate and, hence, genomic regions with heavy methylation tend to have a low observed and/or expected CpG value. A first analysis of the role of DNA methylation in caste differentiation and worker polyphenism was done in L. humile, P. barbatus, H. saltator, C. floridanus and A. cephalotes. For these species, genes involved in reproduction and wing development (traits reserved for queens and males) show genomic signatures of methylation (i.e. a low observed:expected ratio of CG dinucleotides) relative to randomly selected genes [15, 16, 18, 20].

None of the ant genomes show the bimodal distribution of observed and/or expected CpG values in coding sequences that has been observed in honeybees [43, 44]. Ants are missing the distinctive peak of low CpG values present in honeybees that is thought to reflect regions of germ-line methylation. The absence of a distinct bimodal distribution of CpG values does not necessarily mean that methylation does not play a significant role in the division of labor in ants, but given the dramatic difference in the observed distributions, DNA methylation may play a different role in ants than in the honeybee, and different ant lineages may also differ in their use of DNA methylation [41].

So far, in vivo DNA methylation has been experimentally confirmed by HPLC in C. floridanus and H. saltator [15], methylation-dependent immunoprecipitation and sodium bisulfite sequencing in S. invicta [17], and methylation-sensitive AFLP analysis in P. barbatus [20]. Comparison of H. saltator and C. floridanus revealed an interesting trend in methylcytosine content: the more basal ant species, H. saltator, which has less queen worker dimorphism, also showed less methylcytosine in the genome, whereas C. floridanus, which has polymorphic workers and a much more complex social structure, showed more methylcytosine. Hence, DNA methylation might be positively correlated with an increase in social complexity.

Genetic control of caste programs

Pogonomyrmex barbatus promises the most insight into the genetic and epigenetic factors influencing caste determination because it is the only sequenced ant species known to use both environmental (ECD) and genetic forms of caste determination (GCD). Hence, genetic markers allow queen- or worker-destined individuals to be distinguished regardless of developmental stage [45, 46]. This makes it possible to analyze stage-specific expression data, allowing for the identification of the developmental stage when queen and worker developmental programs differentiate, which genes and gene regulatory networks differentiate first, and how those genes are differentially regulated. Once those genes and their gene regulatory networks have been identified, their expression patterns can be tested in other ants to examine whether caste developmental programs are evolutionarily conserved.

Other elements known to be involved in the regulation of caste differences are miRNAs. Several miRNAs were found to be differentially expressed in reproducing (gamergates) and non-reproducing workers of H. saltator. Additionally, mir-64 was differentially expressed in males, minor workers and major workers of C. floridanus [15]. Many miRNAs have been annotated across the ant genomes, providing another level of regulation to probe for caste- and stage-specific differences between the various ant species (Table 2). A first and simple step to explore the function of miRNAs in caste determination in ants or other social Hymenoptera is to test if any of them show a castespecific expression pattern and whether they also play a role in the differentiation of behavioral castes, for example between foragers and nurses.

An environmental factor that specifies whether a honeybee larva differentiates into a queen or into a worker is the protein royalactin [47]. By contrast, ants seem to use many different environmental and genetic factors to determine which larvae develop into queens or workers (Box 1) [1, 48]. Once the basal regulatory mechanism of reproductive caste determination is known for one ant species (e.g. in the GCD form of P. barbatus), it should be possible to use this information to identify the proximate mechanisms of caste determination in other ant species. This will help identify where in the regulatory networks of the ant genome the different environmental and genetic signals converge to initiate caste differentiation.

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

The release of seven sequenced ant genomes and the development of new genomic tools for ants has laid the groundwork for an exciting new era of socio- and ant genomics [13, 14]. It is now possible to study the molecular basis of social behavior in a second taxon that evolved eusociality independently from the honeybee lineage. The first analysis of the seven ant genomes revealed that ants have a different sociogenome compared with that of the honeybee and thatthere is also significant variation among ant sociogenomes. Ants evolved eusociality once but have evolved a wide range of social organization. Comparison of ant species with different levels of social organization and complexity may reveal the molecular changes involved in the evolution of increasingly complex societies [10].

Having multiple genomes also allows for the identification of ant-specific, conserved noncoding regions, similar to the work done in drosophilids [49], and may produce novel regulatory mechanisms. Several other ant genome projects have already been started. The bulldog ant, Myrmecia croslandi (Owain Edwards personal communication), which boasts a single chromosome, should shed light on how genome rearrangements have occurred in ants. Cardiocondyla obscurior (Jan Oettler, personal communication) has great potential because it can be bred in the lab, thus opening the possibility of coupling genetic and reverse genetic approaches. Finally, a genome project is underway for an army ant, Cerapachys biroi (Daniel Kronauer, personal communication), a nomadic hunter of other insects and a representative of the army ant clade that harbors species such as Eciton burchelli or Dorylus molestus, which have a colony structure and life-history similar to that ofthe honeybee. Bothspecieshave been tagged for sequencing and would be the idealtaxa to compare to the honeybee, owing to their similarity in social organization. A comprehensive list of ants prioritized for sequencing can be found on the BGI web site (http://www.ldl.genomics.cn/page/showinsects.jsp).

Ant genomics also promises significant advances in several areas of biomedical research. Aging is one fieldforwhich ants are ideal model organisms because they show huge caste-specific age variation, despite sharing the same genotype (queens can live for more than 30 years, whereas workers rarely live longer than a couple of months [1, 50, 51]). Hence, finding the regulatory mechanism or environmental signals that lead to this age difference may shed light onto the secrets of aging [52]. Furthermore, ants also produce many antibiotic substances [53, 54], and the poison of ants may harbor many pharmacologically useful components, besides being a medical issue (e.g. allergies to fire ant venom). Pogonomyrmex barbatus, for example, has one of the most potent poisons in the animal kingdom. With a genome in hand, many experimental approaches (e.g. proteomics ormetabolomics)arenowfeasible for identifying these substances or the metabolic pathways that produce them.

We are still in the early stages of describing and understanding sociogenomes. In the near future, many more sociogenomes from multiple phylogenetically independent lineages will become available (e.g. termites, social wasps, bumblebees, stingless bees and their close solitary relatives). Their diversity and relevance for issues in human social behavior and genetics make social insects the ideal models for exploring complex social traits and their genetic and epigenetic regulation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Alex Wild and Myrmecos.net for providing images of the sequenced ant species used in Figure 1. JG and CRS were supported by a grant from the NSF (IOS-0920732). CDS was supported by a grant from the NIMH (5SC2MH086071). DS is supported by a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Collaborative Innovation Award #200900 to D. Reinberg, S. Berger, and J. Liebig. YW was supported by a European Research Council grant to Laurent Keller and JR was supported by a Swiss NSF grant to Laurent Keller. SN was supported by the Danish National Research Foundation.

References

-

Hölldobler B. Wilson E.O. The Ants. Belknap Press, 1990

-

Hölldobler B. Wilson E.O. The Superorganism. W.W. Norton and Company, 2009

-

Smith C.R. et al. Ants (Formicidae): models for social complexity. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2009; https://doi.org/10.1101/pdb.emo125

-

Lansing J.S. Complex adaptive systems. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2003; 32: 183-204

-

Bonabeau E. Social insect colonies as complex adaptive systems. Ecosystems. 1998; 1: 437-443

-

Brady S.G. et al. Evaluating alternative hypotheses for the early evolution and diversification of ants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006; 103: 18172-18177

-

Moreau C.S. et al. Phylogeny of the ants: diversification in the age of angiosperms. Science. 2006; 312: 101-104

-

Moreau C.S. Inferring ant evolution in the age of molecular data (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecological News. 2009; 12: 201-210

-

Engel M.S. Grimaldi D.A. Primitive new ants in Cretaceous amber from Myanmar, New Jersey, and Canada (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Am. Museum Novitates. 2005; 3485: 1-24

-

Laubichler M. Gadau J. Social Insects as models for Evo-Devo. in: Gadau J. Fewell J. Organization of Insect Societies. Harvard University Press, 2009: 590-607

-

Smith C.D. et al. Ant genomics: strength and diversity in numbers. Mol. Ecol. 2010; 19: 31-35

-

Honeybee Genome Sequencing Consortium Insights into social insects from the genome of the honeybee Apis mellifera. Nature. 2006; 443: 931-949

-

Robinson G.E. et al. Sociogenomics: social life in molecular terms. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2005; 6: 257-270

-

Smith C.R. et al. Genetic and genomic analyses of the division of labour in insect societies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008; 9: 735-748

-

Bonasio R. et al. Genomic comparison of the ants Camponotus floridanus and Harpegnathos saltator. Science. 2010; 329: 1068-1071

-

Smith C.D. et al. Draft genome of the globally widespread and invasive Argentine ant (Linepithema humile). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011; 108: 5673-5678

-

Wurm Y. et al. The genome of the fire ant Solenopsis invicta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011; 108: 5679-5684

-

Suen G. et al. The genome sequence of the leaf-cutter ant Atta cephalotes reveals insights into its obligate symbiotic lifestyle. PLoS Genet. 2011; 7: e1002007

-

Nygaard S. et al. The genome of the leaf-cutting ant Acromyrmex echinatior suggests key adaptations to advanced social life and fungus farming. Genome Res. 2011; 21: 1339-1348

-

Smith C.R. et al. Draft genome of the red harvester ant Pogonomyrmex barbatus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011; 108: 5667-5672

-

Abouheif E. Wray G. Evolution of the gene network underlying wing polyphenism in ants. Science. 2002; 297: 249-252

-

Li J. Heinz K.M. Genome complexity and organization in the red imported fire ant Solenopsis invicta Buren. Genet. Res. 2000; 75: 129-135

-

Nasonia Genome Working Group Functional and evolutionary insights from the genomes of three parasitoid Nasonia species. Science. 2010; 327: 343-348

-

Kronforst M.R. et al. DNA methylation is widespread across social Hymenoptera. Curr. Biol. 2008; 18: R287-R288

-

Yi S.V. Goodisman M.A.D. Computational approaches for understanding the evolution of DNA methylation in animals. Epigenetics. 2009; 4: 551-556

-

Kucharski R. et al. Nutritional control of reproductive status in honeybees via DNA methylation. Science. 2008; 319: 1827-1830

-

Foret S. et al. Epigenetic regulation of the honey bee transcriptome: unravelling the nature of methylated genes. BMC Genomics. 2009; 10: 472

-

Tweedie S. et al. FlyBase: enhancing Drosophila Gene Ontology annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009; 37: D555-D559

-

Tribolium Genome Sequencing Consortium. (2008) The genome of the model beetle and pest Tribolium castaneum. Nature 452, 949-955.

-

The Gene Ontology Consortium Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nature Genet. 2000; 25: 25-29

-

Endler A. et al. Surface hydrocarbons of queen eggs regulate worker reproduction in a social insect. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004; 10: 2945-2950

-

Moore D. Liebig J. Mixed messages: fertility signaling interferes with nestmate recognition in the monogynous ant Camponotus floridanus. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2010; 64: 1011-1018

-

Engels W. Occurrence and significance of vitellogenin in female castes of social hymenoptera. Am. Zool. 1974; 14: 1229-1237

-

Seehuus S. et al. Reproductive protein protects functionally sterile honey bee workers from oxidative stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006; 103: 962-967

-

Corona M. et al. Vitellogenin, juvenile hormone, insulin signaling, and queen honey bee longevity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007; 104: 7128-7133

-

Nelson C.M. et al. The gene vitellogenin has multiple coordinating effects on social organization. PLoS Biol. 2007; 5: e62

-

Ihle K.E. et al. Genotype effect on regulation of behaviour by vitellogenin supports reproductive origin of honeybee foraging bias. Anim. Behav. 2010; 79: 1001-1006

-

Evans J.D. et al. Immune pathways and defence mechanisms in honey bees Apis mellifera. Insect Mol. Biol. 2006; 15: 645-656

-

Howard Cedar H. Bergman Y. Linking DNA methylation and histone modification: patterns and paradigms. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009; 10: 295-304

-

Kramer J.M. et al. Epigenetic regulation of learning and memory by Drosophila EHMT/G9a. PLoS Biol. 2011; 9: e1000569

-

Lyko F. Maleszka R. Insects as innovative models for functional studies of DNA methylation. Trends Genet. 2011; 27: 127-131

-

Lyko et al. The honey bee epigenomes: differential methylation of brain DNA in queens and workers. PLoS Biol. 2010; 8: e1000506

-

Elango N. et al. DNA methylation is widespread and associated with differential gene expression in castes of the honeybee, Apis mellifera. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009; 106: 11206-11211

-

Wang Y. Leung F.C. In silico prediction of two classes of honeybee genes with CpG deficiency or CpG enrichment and sorting according to gene ontology classes. J. Mol. Evol. 2009; 68: 700-705

-

Schwander T. et al. Two alternate mechanisms contribute to the persistence of interdependent lineages in Pogonomyrmex harvester ants. Mol. Ecol. 2007; 16: 3533-3543

-

Clark et al. Behavioral regulation of genetic caste determination in a Pogonomyrmex population with dependent lineages. Ecology. 2006; 87: 2201-2206

-

Kamakura M. Royalactin induces queen differentiation in honeybees. Nature. 2011; 473: 478-483

-

Schwander T. et al. Nature versus nurture in social insect caste differentiation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010; 25: 275-282

-

Clark A. the Drosophila 12 Genomes Consortium Evolution of genes and genomes on the Drosophila phylogeny. Nature. 2007; 450: 203-218

-

Page Jr., R.E. Peng C.Y-S. Aging and development in social insects with emphasis on the honey bee, Apis mellifera L. Exp. Gerontol. 2001; 36: 695-711

-

Parker J.D. et al. Decreased expression of Cu-Zn superoxide dismutase 1 in ants with extreme lifespan. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004; 101: 3486-3489

-

Keller L. Jemielity S. Social insects as a model to study the molecular basis of ageing. Exp. Gerontol. 2006; 41: 553-556

-

Mackintosh J.A. et al. Isolation from an ant Myrmecia gulosa of two inducible O-glycosylated proline-rich antibacterial peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 1998; 273: 6139-6143

-

Veal D.A. et al. Antimicrobial properties of secretions form the metapleural glands of Myrmecia gulosa (the Australian bullet ant). J. Appl. Microbiol. 2008; 72: 188-194

-

Gotzek D. Ross K.G. Genetic regulation of colony social organization in fire ants: an integrative overview. Q. Rev. Biol. 2007; 82: 201-226

-

Ross K.G. Multilocus evolution in fire ants: effects of selection, gene flow and recombination. Genetics. 1997; 145: 961-974

-

Ross K.G. Keller L. Genetic control of social organization in an ant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998; 95: 14232-14237

-

Oster G.F. Wilson E.O. Caste and Ecology in the Social Insects. Princeton University Press, 1978

-

Tschinkel W.R. The Fire Ants. Belknap Press, 2006

-

Tschinkel W.R. Sociometry and sociogenesis of colonies of the fire ant Solenopsis invicta during one annual cycle. Ecol. Monogr. 1993; 63: 425-457

-

Wilson E.O. Caste and division of labor in leaf-cutter ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Atta): I. The overall pattern in A. sexdens. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1980; 7: 143-156

-

Anderson K.E. et al. The causes and consequences of genetic caste determination in ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecol. News. 2008; 11: 119-132

-

Helms Cahan S. et al. Loss of phenotypic plasticity generates genotype-caste association in harvester ants. Curr. Biol. 2004; 14: 2277-2282

-

Smith C.R. Suarez A.V. The trophic ecology of castes in harvester ant colonies. Funct. Ecol. 2010; 24: 122-130

-

Hughes W.H.O. Boomsma J.J. Genetic polymorphism in leaf-cutting ants is phenotypically plastic. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 2007; 274: 1625-1630

-

Libbrecht R. et al. Genetic component to caste allocation in a multiple-queen ant species. Evolution. 2011; https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01348.x

-

Cahan S. Vinson S.B. Reproductive division of labor between hybrid and nonhybrid offspring in a fire ant hybrid zone. Evolution. 2003; 57: 1562-1570

-

Hughes W.H.O. Boomsma J.J. Genetic royal cheats in leaf-cutting ant societies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008; 105: 5150-5153

-

Wilson E.O. The sociogenesis of insect colonies. Science. 1985; 228: 1489-1495

-

Macom T.E. Porter S.D. Comparison of polygyne and monogyne red imported fire ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) population densities. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1996; 89: 535-543

-

Holway D.A. et al. Loss of intraspecific aggression underlies the success of a widespread invasive social insect. Science. 1998; 282: 949-952

-

Porter S.D. Savignano D.A. Invasion of polygyne fire ants decimates native ants and disrupts arthropod community. Ecology. 1990; 71: 2095-2106

-

Morrison L.W. Long-term impacts of an arthropod-community invasion by the imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. Ecology. 2002; 83: 2337-2345

-

Tillberg C.V. et al. Trophic ecology of invasive Argentine ants in their native and introduced ranges. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007; 104: 20856-20861

-

Tsutsui N.D. et al. The evolution of genome size in ants. BMC Evol. Biol. 2008; 8: 64

Article Info

Publication History

Published online: October 06, 2011

Identification

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2011.08.005

Copyright

© 2011 Elsevier Ltd. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.