Ants, Bees, Genomes & Evolution @ Queen Mary University London

Published: 04 March 2020

Healthy Pollinators: Evaluating Pesticides with Molecular Medicine Approaches

Federico López-Osorio, Yannick Wurm

Trends in Ecology & Evolution (2020)

Abstract

Pollinators have been declining worldwide, and pesticides have contributed to these declines. High-resolution approaches from molecular medicine can provide unparalleled insight into organismal physiology and health. Applying these approaches to pollinators can significantly improve the efficiency and sensitivity of pesticide research and evaluation, and thus the sustainability of modern agriculture.

Pollinators and Pesticide Safety

Pollinators provide an essential service for the reproduction of flowering plants, thereby maintaining ecosystem stability and agricultural productivity. However, many insect pollinator species have been declining because of habitat loss, climate change, pathogens, and exposure to pesticides [1.]. Farmers wanting to protect their crops against pest insects often apply neurotoxic insecticides such as neonicotinoids (see Glossary), which target nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs). Pesticide levels that were considered safe in fact reduce cognitive abilities, foraging performance, and ultimately survival of exposed pollinators [2.]. Such findings led, for example, the European Commission to ban outdoor use of three common neonicotinoids in 2018. Meanwhile, other neonicotinoids and novel pesticides that also target nAChRs remain approved, perhaps because less is known about their negative effects.

The ban of previously authorised neonicotinoids serves as a warning that the processes for evaluating pesticide safety could improve. Traditionally, survival of Apis mellifera honey bees after pesticide exposure was considered a sufficient measure of toxicity. Recommendations now include examining short- and long-term effects of exposure on behaviour and survival of multiple species of social and solitary bees [3.]. Such improvements to pesticide evaluation processes should be applauded. Further improvements would incorporate understanding of an even broader diversity of pollinator species and conditions.

An ideal risk assessment process would rigorously account for variation in susceptibility across species and life stages (Box 1); consider how pesticide compounds may interact with each other or with other environmental stressors; and use ecologically relevant measurements, such as long-term reproductive and pollination abilities. Unfortunately, the scale of experimentation required by such an evaluation process using traditional approaches likely makes it unfeasible.

Box 1

Molecular Basis of Variation in Pesticide Susceptibility

The metabolism or sequestration of neurotoxic insecticides first occurs in directly exposed tissues such as the gut, then in Malpighian tubules. Genomes of insect pollinators can encode hundreds of detoxification enzymes that originated millions of years ago to cope with toxins naturally produced by flowering plants or found in other food sources. These detoxification enzymes include cytochromes P450, carboxylesterases, and glutathione S-transferases [6.]; each specialised in particular biochemical reactions. These enzymes can sometimes help detoxification of pesticides. For example, Apis mellifera honey bees and Bombus terrestris bumble bees each possess single P450 enzymes that efficiently metabolise thiacloprid, while only poorly metabolising imidacloprid [9.].

The pharmacokinetic rates at which detoxification occurs or pesticides spread to the central nervous system and effector tissues, and the affinities of compounds for their targets will vary extensively across species and pesticides. There can also be extensive variation within species. For example, not all nAChRs are created equal. Each nAChR comprises five protein subunits; insect genomes typically encode 10–12 possible subunits. Differential use of the broad diversity of possible receptors likely occurs across cell types and life stages. The differential binding of pesticides to different subunits may lead to broad variation in possible effects.

Approaches from Molecular Medicine Can Provide Detailed Insight

Molecular medicine approaches that provide thousands to millions of measurements per sample have revolutionised research on human diseases, development of new medicines, and patient care. For example, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) delivers expression levels for each of thousands of genes in a sample. RNA-seq is now an essential toxicogenomic approach for evaluating risks of medicinal drugs for humans [4.]. Similarly, RNA-seq of cancer biopsies enables the discovery of novel cancer subtypes, improving clinical diagnosis and helping guide treatment [5.].

We believe that approaches from molecular medicine are powerful alternatives to traditional procedures for evaluating impacts of environmental stressors on pollinator health. Early studies demonstrate the feasibility of applying the new technologies on pollinators [6., 7., 8., 9.]. Their large-scale application can dramatically improve our understanding of how pesticides affect pollinators, identify how other stressors modulate detrimental effects, provide a novel approach for pesticide classification, and help direct laboratory and field experiments.

Overview of Molecular Effects of Pesticides on Pollinators

We need extensive RNA-seq efforts to understand how gene expression changes in particular tissues after exposure to individual pesticides. Such efforts should encompass a phylogenetically representative diversity of pollinator species to clarify which effects are similar across species. Moreover, such efforts should incorporate the diversity of life stages and forms (immature stages, sexes, morphs or castes, ages), as well as intensities and durations of exposure to understand how toxicity varies within species. Importantly, gene expression analysis should include detoxification tissues such as Malpighian tubules, effector tissues such as muscles, which underpin locomotor abilities, and mushroom bodies of the central nervous system, which underlie learning and memory. Gene expression changes in detoxification tissues will identify genes involved in the breakdown of compounds. The intensities of gene expression changes in tissues such as brain or muscle will provide measures of toxicity and indicate which types of molecular pathways the pesticides disrupt to produce organism-wide effects, including impaired learning and motor control. Comparisons across species, pesticides, and conditions will provide much-needed understanding of the diversity of negative effects of pesticides that must be considered when evaluating toxicity.

Understanding Interactions between Pesticides and Other Environmental Stressors

Pollinators commonly encounter multiple environmental stressors, such as mixtures of pesticides, nutritional deficiency, and pathogens. Experiments in honey bees have shown that such stressors can interact: fungicides increase the lethality of neonicotinoids [10.]; neonicotinoids increase susceptibility to pathogens [10.]; and pollen consumption reduces sensitivity to some pesticides [7.]. RNA-seq gene expression profiling after experimental exposure to combinations of stressors will clarify whether such interactions are due to changes in the same molecular pathways, to effects on different pathways, or to interactions, such as one stressor suppressing the response to another stressor. Designing experiments that are able to estimate interactions will be needed when evaluating risks of pesticides, while additive effects will be simpler to determine.

Classifying Pesticides Based on Their Effects

Pesticides are classified based on their chemical structure. However, even subtle structural changes can have dramatic consequences on toxicity by affecting pharmacokinetics, or by modulating the duration or intensity of binding to different subpopulations of target receptors. For example, the neonicotinoids thiacloprid and imidacloprid differ only slightly in their chemical structures, yet their toxicities to honey bees and bumble bees differ substantially [9.]. This variation in sensitivity to pesticides seems to result primarily from differences in the ability of P450 enzymes to metabolise such compounds, rather than due to differences in pesticide affinity for nAChRs [9.].

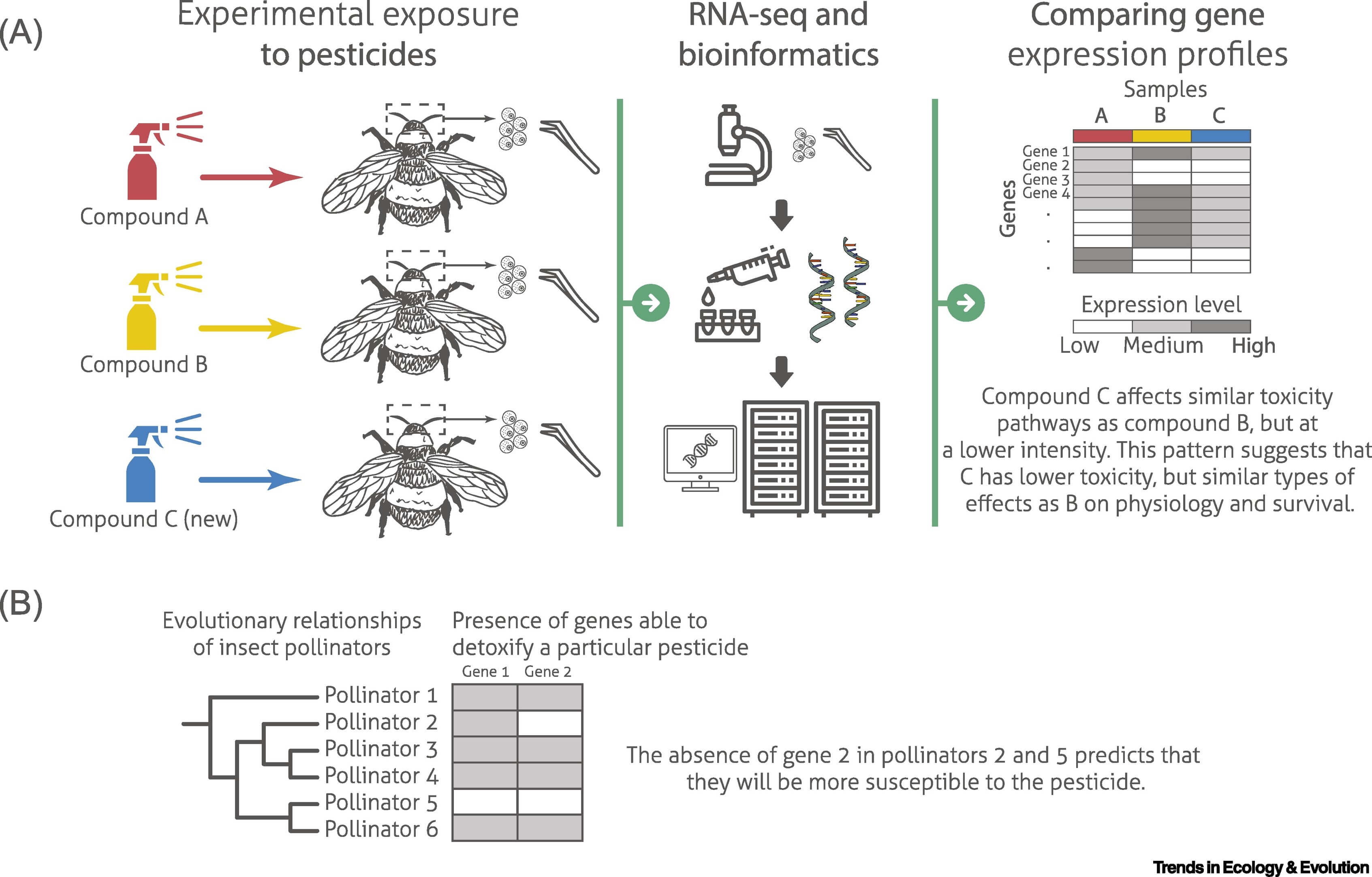

Gene expression profiles and traditional liver toxicity measurements for 200 human drugs were combined to successfully predict toxicity of other drugs based on gene expression alone, and were more informative than chemical classification [11.]. Pesticides should be similarly classified based on how they affect gene expression profiles. If a new potential pesticide leads to similar expression profiles in specific tissues as one that was previously studied, it will likely have similar effects on physiology and survival (Figure 1A). Performing gene expression assays for such comparisons on representative tissues, such as those highlighted above is important because it provides much higher sensitivity and understanding of pharmacological variation compared with performing RNA-seq on entire organisms. This will represent a pragmatic means of estimating toxicity, and thus can be used as a screening mechanism to guide the tests of behaviour or survival most able to fully diagnose toxicity.

Figure.1

Applications of Molecular Diagnostic Approaches to Assess the Effects of Pesticides.

(A) Hypothetical example in which pollinators were exposed to two established pesticides (A and B) and a newly introduced compound (C). After 2 weeks of exposure, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) was performed on brains. These data reveal that compound C affects gene expression in a similar manner as compound B, but the intensities were lower for C than B. These results suggest that exposure to the new compound C affects similar toxicity pathways as compound B, but to a weaker extent. Knowledge of organism-level effects could thus be extrapolated from B to C. (B) Independent experiments demonstrated that gene 1 and gene 2 play key roles in the breakdown of a particular compound. Among six pollinator species considered, gene 1 is present in all species except pollinator 5, and gene 2 is present in all species except pollinators 2 and 5. This pattern suggests that pollinator 2 and in particular pollinator 5 will be more susceptible to the compound than the other species. This figure includes icons retrieved from thenounproject.com (CC BY license; creators: Ben Davis, Iyikon, Gorkem Oner, Monkik, Dmitry Mirolyubov, Zlatko Najdenovski, Nociconist, Tatyana).

Towards a Framework for Predicting Susceptibility Based on Genome Sequence

Our understanding of how specific detoxification genes and target receptor sequences modulate toxicity of particular pesticides will increase. While unable to account for the risks of exposure, sufficient knowledge will make it possible to predict the susceptibility of a species to a pesticide based on the presence and sequence of genes in its genome (Figure 1B). For example, the absence of particular cytochromes P450 in the alfalfa leafcutter bee, Megachile rotundata, likely explain its >2500-fold higher sensitivity to the neonicotinoid thiacloprid relative to other managed bees [12.]. Large-scale projects have begun to generate genome sequences for hundreds of pollinator species, paving the way to predicting toxicity of particular pesticides on entire communities of pollinators.

Assessing the Health of Wild-Caught Pollinators

Much understanding of the health of wild pollinators comes from long-term sampling studies. Indeed, except for the most extreme cases, looking at a pollinator cannot reveal whether it is unwell. Tissue-specific gene expression profiling from wild pollinators can provide the missing link by clarifying how much the body is currently investing in detoxification and immune defence, and whether, for example, brain and muscle tissue are functioning within the normally expected range. The insight gained through this approach could provide rapid and up-to-date indications of the impacts of ongoing environmental challenges and inform local management decisions.

Concluding Remarks

The extensive ongoing declines of pollinators call for major changes in how we treat the natural world. Approaches from molecular medicine can provide high-resolution insight into the diverse modes of action of pesticides and their effects on pollinators. The resulting knowledge and tools are unlikely to fully replace traditional toxicity trials, but can help understand and predict the vulnerability of diverse pollinator species to existing and future pesticides. This will pinpoint which toxicity trials are needed and thus pragmatically increase our efficiency and sensitivity for evaluating pollinator health for research and regulation. Ultimately, molecular approaches can facilitate the identification of compounds that potentially have minimal collateral effects on beneficial species, and therefore improve the sustainability of agricultural practices.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Natural Environment Research Council ( NE/L00626X/1 ) and by the European Commission ( H2020-MSCA-IF-2018-840185 ). We thank Andrea Stephens and two anonymous reviewers for comments that improved our manuscript.

References

-

Potts S.G. et al. Safeguarding pollinators and their values to human well-being. Nature. 2016; 540: 220-229

-

Klein S. et al. Why bees are so vulnerable to environmental stressors?. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2017; 32: 268-278

-

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) Guidance on the risk assessment of plant protection products on bees (Apis mellifera, Bombus spp. and solitary bees). EFSA J. 2013; 11: 3295

-

Liu Z. et al. Toxicogenomics: a 2020 vision. Trends Pharmac. Sci. 2019; 40: 92-103

-

Cieślik M. Chinnaiyan A.M. Cancer transcriptome profiling at the juncture of clinical translation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018; 19: 93-109

-

Berenbaum M.R. Johnson R.M. Xenobiotic detoxification pathways in honey bees. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2015; 10: 51-58

-

Grozinger C.M. Robinson G.E. The power and promise of applying genomics to honey bee health. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2015; 10: 124-132

-

Colgan T.J. et al. Caste- and pesticide-specific effects of neonicotinoid pesticide exposure on gene expression in bumblebees. Mol. Ecol. 2019; 28: 1964-1974

-

Manjon C. et al. Unravelling the molecular determinants of bee sensitivity to neonicotinoid insecticides. Curr. Biol. 2018; 28: 1137-1143.e5

-

Wood T.J. Goulson D. The environmental risks of neonicotinoid pesticides: a review of the evidence post 2013. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017; 24: 17285-17325

-

Kohonen P. et al. A transcriptomics data-driven gene space accurately predicts liver cytopathology and drug-induced liver injury. Nat. Commun. 2017; 8: 15932

-

Hayward A. et al. The leafcutter bee, Megachile rotundata, is more sensitive to N-cyanoamidine neonicotinoid and butenolide insecticides than other managed bees. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019; 3: 1521-1524

Glossary

Cytochromes P450

family of monooxygenase enzymes important for metabolism of toxic exogenous compounds such as natural plant substances and pesticides as well as synthesis and breakdown of pheromones, cuticular hydrocarbons, and hormones.

Malpighian tubules

excretory and osmoregulatory system found in most insects and other arthropods. These tubules are a major site of expression of detoxification genes.

Neonicotinoids

neurotoxic pesticides used to protect crops from harmful insects. Coating seeds with neonicotinoids ensures absorption and translocation of compounds throughout plant structures, including flowers. Cyano-substituted neonicotinoids (e.g., thiacloprid) are less toxic to insect pollinators than nitro-substituted neonicotinoids (e.g., imidacloprid). Neonicotinoids were initially considered harmless to humans, but recent evidence suggests otherwise. Several other types of pesticides (e.g., the sulfoximine sulfoxaflor and the butenolide flupyradifurone) have similar modes of action as the neonicotinoids.

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs)

ligand-gated ion channels embedded in cell membranes, mediating synapses and playing important roles in cognitive processes. Each nAChR consists of five subunits arranged around a central pore. Insects usually have small gene families encoding nAChR subunits (e.g., 11 genes in the honey bee). The neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) binds to the nAChR to open the channel, allowing sodium and potassium ions to pass through. Neonicotinoids and other pesticides such as sulfoximines cause toxicity by replacing ACh.

Pharmacokinetics

the study of uptake of drugs by organisms, including the time course of absorption, distribution throughout the body, metabolism, and excretion of drugs.

RNA-seq

application of deep-sequencing technologies to catalogue RNA molecules and their levels of expression in biological samples.

Toxicogenomics

the study of molecular responses to toxic substances using high-throughput genomic technologies to profile transcripts, proteins, and metabolites.

Article Info

Publication History

Published online: March 04, 2020

Identification

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2019.12.012

Copyright

© 2020 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd.

User License

Creative Commons Attribution – NonCommercial – NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

ScienceDirect

Access this article on ScienceDirect