Ants, Bees, Genomes & Evolution @ Queen Mary University London

First published: 20 November 2021

Larger, more connected societies of ants have a higher prevalence of viruses

Anindita Brahma, Raphael Gray Leon, Gabriel Luis Hernandez, Yannick Wurm

Molecular Ecology (2022), 31:859-865

Abstract

The benefits of cooperative living for foraging, nesting, defence and buffering environmental challenges lead animals with the most highly social lifestyles to dominate many ecosystems. However, living in larger, more highly connected groups should also increase the risks of pathogen exposure and transmission. While over long timescales selective responses could buffer the impacts of potential higher pathogen prevalence, similar processes are unlikely over short timescales. The red fire ant Solenopsis invicta is ideal for measuring the effects of group size on pathogen prevalence because two types of society coexist in this species: smaller single-nest single-queen colonies that are highly aggressive to their neighbours and larger multiple-queen colonies that exchange resources with neighbouring nests. We compare the presence of viruses between these two colony types using metagenomic sequence classification of RNA-sequencing reads. We find that queens from multiple-queen colonies have 8.3-times higher viral load and 1.5-times higher viral diversity than queens from single-queen colonies. This finding characterizes a rarely considered cost of transitions to more highly social living. Furthermore, our results show that highly social invertebrates can harbour many viruses.

1. Introduction

The reduced risk of predation, increased foraging efficiency and resource sharing of group-living contribute to the dominance of social insects in most terrestrial ecosystems. However, because group-living increases the frequency of interactions among individuals, it should also lead to greater transmission and prevalence of pathogens (Schmid-Hempel, 2017). Higher pathogen load could represent a substantial cost to social living that is rarely considered in models of social evolution. Comparisons between species of birds or mammals suggest that pathogen load increases with group size (Nunn et al., 2015; Schmid-Hempel, 2017). However, the species involved in such comparisons differ substantially in terms of ecological niches and evolutionary histories. It thus remains unclear if increases in group size result in higher pathogen loads. To test this, one should ideally compare the pathogen load in different social contexts within the same species.

The red fire ant Solenopsis invicta is an ideal natural system for testing how increases in group size and social interactions affect pathogen load because two types of society coexist in this species: smaller single-queen colonies (monogyne colonies) and larger multiple-queen colonies (polygyne colonies) that also have higher worker densities (Ross & Keller, 1996; Tschinkel, 2006). To compare pathogen load between the two social forms, we focused on viruses for two reasons. First, their prevalence can be readily measured from RNA (Valles, 2012). Furthermore, viruses are important contributors to colony death in social bees (McMahon et al., 2015; Steinhauer et al., 2018), and thus potentially also in other social insects. Here, we compiled a database of 13,758 genomes of viruses, including 1553 known to infect insects (Brister et al., 2015; Käfer et al., 2019; Valles & Rivers, 2019). Most of these insect viruses (71%) are RNA viruses and thus should be detectable in RNA extracted from infected hosts. We counted viral sequences present in the RNA obtained from queens from single-queen and multiple-queen fire ant colonies. We then compared viral load and viral diversity between the two forms of social organization.

2. Materials and Methods

We used published RNA-sequencing (RNA-Seq) data from six data sets containing 22 single-queen and 27 multiple-queen colonies (Arsenault et al., 2020; Chandra et al., 2018; Manfredini et al., 2021; Martinez-Ruiz et al., 2020; Morandin et al., 2016; Wurm et al., 2011). All colonies had been sampled in North America (sample collection locations are provided in the Supporting Information Data Set), and total RNA was extracted from whole bodies or brains of queens followed by Illumina library preparation from cDNA of mRNA. We ran kraken 2.0.8 (Wood et al., 2019) to obtain reads assigned to viral families and number of viral species in each queen sample and used these as response variables for viral load and viral diversity analyses, respectively. All computation was performed on the Apocrita High Performance Computing environment http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.438045.

We only considered queens for our study because they probably provide the best measure of effective viral load in a colony. Indeed, after their mating flight, queens never leave the protection of the nest and only eat food that other colony members have digested; queens thus avoid direct exposure to viruses. Furthermore, infected queens stay in the colony (Giehr & Heinze, 2018), while social immune defence mechanisms can lead workers to leave or be excluded (Cremer et al., 2007). Preliminary analyses of a small data set from workers support the trends we find in queens (data not shown).

2.1 Creating KRAKEN2 database for viral read estimation

We downloaded the viral and nucleotide (nt) databases from ncbi (downloaded on April 20, 2020) and combined them to create a database for the taxonomic classification tool KRAKEN2 (version 2.8.0; Wood et al., 2019). We further downloaded the genome sequences of 231 newly identified insect viruses (Käfer et al., 2019) and added these to our KRAKEN2 database. We used this combined database for taxonomic classification of the RNA-Seq reads obtained from whole body or brains of S. invicta queens from single-queen and multiple-queen colonies (Arsenault et al., 2020; Chandra et al., 2018; Manfredini et al., 2021; Martinez-Ruiz et al., 2020; Morandin et al., 2016; Wurm et al., 2011). Because our KRAKEN2 database contained the S. invicta genome, KRAKEN2 could classify any reads from endogenous viral elements to the genus Solenopsis and not as free infectious viruses.

2.2 Estimation of viral load from gene expression data

For each of the 22 single-queen and 27 multiple-queen colonies, we used published RNA-Seq data from whole bodies (three single-queen and eight multiple-queen colonies; BioProject PRJDB4088 and PRJNA629802; Morandin et al., 2016; Wurm et al., 2011) or brains of queens (19 single-queen and 19 multiple-queen colonies; BioProject PRJNA525584, PRJNA472392, PRJNA542606 and PRJNA629802; Arsenault et al., 2020; Chandra et al., 2018; Manfredini et al., 2021; Martinez-Ruiz et al., 2020). All colonies were sampled in North America (see Supporting Information Data Set). Total RNA was extracted from whole bodies or brains of queens, followed by Illumina library preparation from total RNA after ribodepletion (Manfredini et al., 2021) or from enriched mRNA (Arsenault et al., 2020; Chandra et al., 2018; Martinez-Ruiz et al., 2020; Morandin et al., 2016; Wurm et al., 2011).

We ran kraken 2.0.8 (Wood et al., 2019) on each sample using the database described above. We chose kraken2 over other bioinformatic tools due to its sensitivity towards partial matches, which provides greater power for identifying divergent viral sequences in the raw data. To minimize the potential effects of contaminants, presence of Illumina adapters or variation in library qualities, we ignored the total numbers of reads present in the raw data. Instead, we only retained reads assigned to viruses and to the genus Solenopsis. The sum of these two categories of reads was used to normalize the viral reads obtained from each queen sample.

2.3 Comparison of viral load and viral diversity between the two social forms

The first part of the analysis was done using the six data sets with 22 single-queen and 27 multiple-queen colonies. Two of these data sets involved RNA-Seq from whole bodies (Morandin et al., 2016; Wurm et al., 2011) of S. invicta queens, while the other four data sets involved RNA-Seq from brains of S. invicta queens (Arsenault et al., 2020; Chandra et al., 2018; Manfredini et al., 2021; Martinez-Ruiz et al., 2020). For a second analysis, we focused on one of the data sets (BioProject PRJNA629802) containing RNA-Seq from brains of eight queens from eight single-queen colonies and three queens per colony from each of eight multiple-queen colonies (Arsenault et al., 2020). This was one of the most balanced datasets among the six and contained queens from both social forms. This second analysis represented a control for us to avoid potential noise among datasets due to the differences in season or site of collection, or sequencing library creation protocol. It thus allowed us to independently investigate the robustness of the results that had been derived using all six data sets. Because this dataset contained brain RNA-Seq data, it further avoided any viral fragments that could come from ingested food or be present on the cuticle. Finally, the Arsenault dataset enabled us to control whether variants of the fire ant “social supergene”—a large region of “social” chromosome 16—affect viral load or viral diversity. This is because the data set included queens carrying all possible combinations of supergene variants: each multiple-queen colony included one SB/SB queen, one SB/Sb queen and one Sb/Sb queen. Social chromosome variants had been determined using a PCR (polymerase chain reaction) assay of the Gp-9 marker locus (Valles & Porter, 2003). We extracted the reads assigned to the viral families and viral species from queens across all six data sets. To minimize the potential effects of barcode hopping, we retained for each sample only the viral families and species with 100 or more reads.

We applied generalized linear mixed-effects models in “lme4” (version 1.1.21) in R (version 3.6.0) to compare viral load and viral diversity between the two social forms. We used the reads assigned to viral families and the total number of viral species as response variables for the viral load and viral diversity analyses, respectively. We respectively used binomial and Poisson error structures for the mixed-effects models fitted for the viral load and viral diversity analyses. We used the “DHARMa” package (version 0.3.3.0) in R to check for the presence of overdispersion or nonuniformity of the residuals in the fitted models. Our models had neither significant overdispersion nor nonuniformity of the residuals.

To calculate the fold-changes in viral load and viral diversity in multiple-queen colonies, we used the “effects” package (version 4.2.0) in R. This package calculated the model estimated means for the two social forms. We divided the estimate for multiple-queen social form by that of the single-queen social form to obtain the fold-change. Similarly, we calculated the confidence intervals around the fold-change using the confidence intervals around the individual estimates of the two social forms.

3. Results

We analysed 1.77 billion independent RNA-Seq reads from whole bodies and brains of queens with one sample from each of 22 single-queen colonies and up to three samples from each of 27 multiple-queen colonies (i.e., on average 25 million independent reads from each sample; see Supporting Information Data Set for details; Arsenault et al., 2020; Chandra et al., 2018; Manfredini et al., 2021; Martinez-Ruiz et al., 2020; Morandin et al., 2016; Wurm et al., 2011). Applying the kraken2 taxonomic classifier revealed that each sample included a median of 4380 sequence reads from viruses, representing 0.04% of the retained RNA sequence reads (range 0.008%–23.78%). Queens from the 49 colonies carried 41 viral species from across 29 virus families (lists and read counts of viral species and families are provided in the Supporting Information Data Set).

Incorporating data from multiple RNA-Seq datasets should increase analysis power but could also reduce signal due to potential dataset-specific effects. We thus performed each analysis twice. We first used one sample per colony from each of the 22 single-queen and 27 multiple-queen colonies from across six data sets (Arsenault et al., 2020; Chandra et al., 2018; Manfredini et al., 2021; Martinez-Ruiz et al., 2020; Morandin et al., 2016; Wurm et al., 2011; see Supporting Information materials and methods and Supporting Information Data Set for details). We additionally performed a focused analysis on a data set that included one queen from each of eight single-queen colonies and three queens from each of eight multiple-queen colonies (Arsenault et al., 2020). Because this data set included only brain tissue, it is highly unlikely that any of the viral fragments it contains represent contamination from the cuticle or from food.

3.1 Higher viral load in multiple-queen colonies

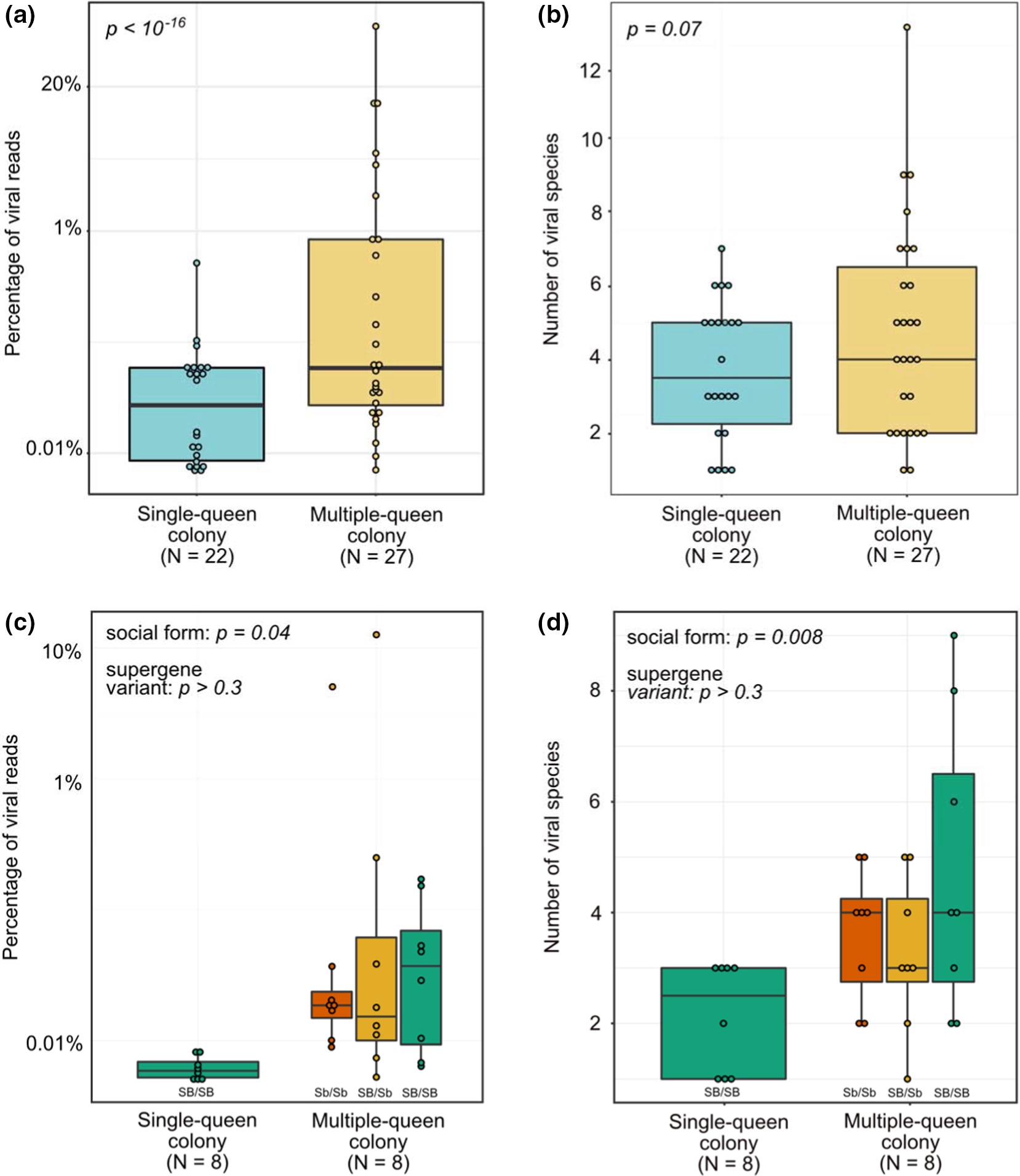

We compared viral load between fire ant queens from single- and multiple-queen colonies. For this, we used a generalized linear mixed-effects model, which included social form as a fixed effect and data set as a random effect, and queen nested inside data set. Queens from multiple-queen colonies had 8.3-fold higher viral load than queens from single-queen colonies (p < 10 −16, confidence intervals of estimate =7.8- to 8.8-fold; Figure 1a). For the analysis focusing on one dataset (Arsenault et al., 2020), we applied a generalized linear mixed-effects model where social form and queen genotype were fixed effects, with colony being a random effect, and queen nested inside colony. This more focused analysis similarly found that multiple-queen colonies had 5-fold higher viral load than single-queen colonies (p = .04; confidence intervals of estimate: 3.7- to 9.2-fold; Figure 1c).

Figure.1

Viral load and viral diversity are higher in queens from multiple-queen colonies than in queens from single-queen colonies. Values of N indicate the number of colonies. (a) Viral load and (b) viral diversity in each sample across six data sets. (c) Viral load and (d) viral diversity comparison using one data set that includes only brain samples, and for which each multiple-queen colony includes three queens carrying distinct variants of the fire ant social supergene (Arsenault et al., 2020)

3.2 Higher viral diversity in multiple-queen colonies

We compared viral diversity between fire ant queens from single- and multiple-queen colonies. For this, we used a generalized linear mixed-effects model with social form as a fixed effect and data set as a random effect. Queens from multiple-queen colonies had marginally higher viral diversity than queens from single-queen colonies (p = .07; estimate = 1.5-fold; confidence intervals of estimate = 0.09- to 2.3-fold; Figure 1b). For the analysis focusing on one data set (Arsenault et al., 2020), we applied a generalized linear mixed-effects model where social form and queen genotype were fixed effects, with colony being a random effect, and queen nested inside colony. This more focused analysis found that multiple-queen colonies had 2.2-fold higher viral diversity (median four species) than single-queen colonies (median = 2.5 species; p = .008; confidence intervals of estimate = 1.2- to 4-fold; Figure 1d).

3.3 Higher viral load and diversity are not due to degeneration of the fire ant social supergene

Preliminary exploration of the data set containing three queens per multiple-queen colony (Arsenault et al., 2020) revealed that there can be an up to 9.3-fold difference in viral load and 2.3-fold difference in viral diversity among queens of the same colony (median pairwise differences were respectively 2.9- and 1.4-fold). A potential explanation for the variation among colony queens and for differences between the two social forms could come from multiple-queen colonies harbouring the Sb variant of a 30-Mb supergene (Pracana, Levantis, et al., 2017; Pracana et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2013). The Sb variant of this genomic region is degenerating in terms of sequence (Pracana, Levantis, et al., 2017; Pracana, Priyam, et al., 2017; Stolle et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2013) and gene expression (Martinez-Ruiz et al., 2020). This degeneration could limit the function of the more than 450 genes in the supergene region, which include at least 15 immune genes. We thus tested whether viral load or viral diversity varies among young queens carrying different supergene genotypes (SB/SB, SB/Sb and Sb/Sb). This was not the case (all comparisons; p > .3; Figure 1c,d).

3.4 High prevalence of previously characterized and novel Solenopsis invicta viruses

More than 98.96% of viral reads in our data set were from Solenopsis invicta viruses 1, 2, 3, 7 and 10, or from Solenopsis invicta tenuivirus. This pattern reinforces the idea that the viral reads detected represent true infections rather than any sort of contamination. The pattern also supports findings that North American S. invicta colonies can carry high loads of these previously characterized viruses (Valles, 2012; Valles & Rivers, 2019; Xavier et al., 2021). Among the 37 of 65 queen samples infected with one of these viruses at a level above our cut-off threshold, only one was from a single-queen colony; it was infected with Solenopsis invicta tenuivirus. When a sample was infected with one of these six previously characterized S. invicta viruses, these were typically the most prevalent viruses: among the 37 samples only one had a higher prevalence of a different virus: a sample from a multiple-queen colony infected with a Solumvirus. All of the 28 other queen samples were infected by at least one virus at a level above our cut-off threshold. Among the eight other previously characterized S. invicta viruses in our database, six were present at levels above our cut-off threshold in some of our samples, despite only three of these viruses having previously been detected in North America (Allen et al., 2011).

4. Discussion

We showed that fire ant queens from multiple-queen colonies have 8.3-fold higher viral load and 1.5-fold higher viral diversity than queens from single-queen colonies. These estimates of pathogen loads represent rare measures of the cost of living in larger societies (Schmid-Hempel, 2017).

Our results hold even if we restrict our analyses to only the six highly prevalent, previously characterized Solenopsis invicta viruses. This is in line with previous RT-PCR-based studies showing that S. invicta colonies can be infected by multiple viruses (Allen et al., 2011), and that multiple-queen colonies had higher infection rates for certain viruses than single-queen colonies (Valles et al., 2010). While our study focused on samples from the invasive North American range of S. invicta, we would expect the general pattern to also hold in colonies from the native South American range of this species.

Demographic differences between single- and multiple-queen fire ant colonies could be sufficient to explain the higher viral load and viral diversity in multiple-queen colonies. Indeed, a greater number of workers foraging for food increases the cumulative risk that one of them becomes infected with a virus. Furthermore, a higher density of workers within the nest should increase pathogen transmission rates. However, at least four additional differences in life-history traits between the two social forms could also contribute to the observed pattern. First, the new queens that regularly join established multiple-queen colonies represent potential vectors of pathogen infection—carrying pathogens from their maternal colony or their mate (Tschinkel, 2006). Second, workers from multiple-queen colonies are less aggressive towards conspecifics from other colonies than workers from single-queen colonies (Tschinkel, 2006; Vander Meer et al., 1990). Interactions such as antennation with individuals from other colonies potentially increase the horizontal transmission of viruses between colonies. Third, S. invicta queens from multiple-queen colonies have smaller fat bodies than queens from single-queen colonies (Keller & Ross, 1993; Tschinkel, 2006). Fat bodies are important for reproduction and immune defence, so having smaller fat bodies could lead to overall lower immune investment (Schwenke et al., 2016). Finally, reproductive competition between queens in multiple-queen colonies (Tschinkel, 2006; Vargo, 1992) may lead them to invest a smaller proportion of their resources towards immunity.

Genetic diversity among colony members may also affect virus acquisition and transmission (van Baalen & Beekman, 2006; Schmid-Hempel, 2017). On the one hand, higher genetic diversity could provide a broader range of immune defence responses (Schmid-Hempel, 2017). On the other hand, higher genetic diversity means the society is more likely to include hosts susceptible to different virus strains (van Baalen & Beekman, 2006). Individuals that have lower resistance to viral infection could become intracolony reservoirs of viral pathogens. This, in turn, might provide the opportunity for viruses to adapt to the genetic background of the colony before infecting the more immune-resistant colony members. Given that multiple-queen fire ant colonies have greater genetic diversity than the single-queen colonies (Ross, 1993; Tschinkel, 2006), the patterns we observe concur with the latter prediction of higher pathogen load in a society with higher genetic diversity, with the caveat that the behavioural and ecological differences discussed above preclude us from testing this unambiguously. Our findings are also in line with those from another socially polymorphic ant, Formica selysi, where workers from multiple-queen colonies had a lower survival rate than those from single-queen colonies after infection by a fungal pathogen (Reber et al., 2008).

Some ant species, including the Argentine ant Linepithema humile and the multiple-queen form of S. invicta, can have supercolonial or even unicolonial social organization, whereby individuals mix freely across tens to thousands of nests. While unicolonial organization can be due to genetic drift associated with an invasion bottleneck, supercolonial organization is probably advantageous in some competition for habitats. Our results highlight that the costs of viral load could also be significant in such contexts. We hypothesize that pathogen load contributes to the high turnover of Argentine ant supercolonies (Vogel et al., 2009). Similarly, high pathogen load could explain why some populations of multiple-queen fire ants, which are generally thought to be favoured in stable habitats, can go extinct and be replaced by populations of single-queen colonies (Tschinkel, 2006).

Overall, our analyses of viral load and viral diversity in a species that includes two types of societies allow us to quantify the cost of a more highly social lifestyle. The rarely considered cost of higher viral loads could be a key selective pressure against the maintenance of larger group sizes. Our work also highlights that colonies of highly social insects can harbour many viruses. Analyses of other invasive ant species such as the common red ant Myrmica rubra, the Argentine ant L. humile and the yellow crazy ant Anoplolepis gracilipes showed that they can serve as reservoirs and alternative hosts for the deformed wing virus, Kashmir bee virus, black queen cell virus, Israeli acute paralysis virus and sacbrood virus, all of which reduce the lifespan of honeybee workers and colonies (Cooling et al., 2017; Gruber et al., 2017; Levitt et al., 2013; Schläppi et al., 2019; Sébastien et al., 2015). The red fire ant S. invicta is also an invasive pest (Ascunce et al., 2011), and ants play major roles in terrestrial ecosystems worldwide. The high viral prevalence we observe in multiple-queen colonies of the red fire ant suggest that these colonies could also potentially facilitate the transmission or survival of viruses affecting other species.

Acknowledgements

We thank Raphaella Jackson and Anurag Priyam for helpful discussions, and Sylvia Cremer, Rodrigo Pracana and Federico Lopez-Osorio for comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript. We thank two anonymous referees for their helpful suggestions for improving the manuscript. This work was funded by the European Commission (H2020-MSCA-IF-2018-842592), the Natural Environment Research Council (NE/L00626X/1), BBSRC (BB/M009513/1, BB/T015683/1) and Fundación para el futuro de Colombia (COLFUTURO).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Y.W. and R.G.L. conceived the study. A.B. and Y.W. designed the study. A.B. analysed the data. G.L.H provided data on immunity-related genes. A.B., R.G.L. and Y.W. wrote the paper. All authors contributed to improving the manuscript.

Open Research Badges

This article has earned an Open Data Badge for making publicly available the digitally-shareable data necessary to reproduce the reported results. The data is available at GitHub https://github.com/wurmlab/Fire_ant_viral_load.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used in this study are available in the Supporting Information. All analysis code is available on GitHub https://github.com/wurmlab/Fire_ant_viral_load.

Supporting Information

Supplementary Material

mec16284-sup-0001-SupInfo.xlsx – [application/excel, 778.3 KB]

Please note: The publisher is not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting information supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing content) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

-

Allen, C., Valles, S. M., & Strong, C. A. (2011). Multiple virus infections occur in individual polygyne and monogyne Solenopsis invicta ants. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 107(2), 107– 111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jip.2011.03.005

-

Arsenault, S. V., King, J. T., Kay, S., Lacy, K. D., Ross, K. G., & Hunt, B. G. (2020). Simple inheritance, complex regulation: Supergene-mediated fire ant queen polymorphism. Molecular Ecology, 29, 3622– 3636. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15581

-

Ascunce, M. S., Yang, C.-C., Oakey, J., Calcaterra, L., Wu, W.-J., Shih, C.-J., & Shoemaker, D. (2011). Global invasion history of the fire ant Solenopsis invicta. Science, 331(6020), 1066– 1068. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1198734

-

Brister, J. R., Ako-Adjei, D., Bao, Y., & Blinkova, O. (2015). NCBI viral genomes resource. Nucleic Acids Research, 43(D1), D571– D577. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gku1207

-

Chandra, V., Fetter-Pruneda, I., Oxley, P. R., Ritger, A. L., McKenzie, S. K., Libbrecht, R., & Kronauer, D. J. C. (2018). Social regulation of insulin signaling and the evolution of eusociality in ants. Science, 361(6400), 398– 402. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aar5723

-

Cooling, M., Gruber, M. A. M., Hoffmann, B. D., Sébastien, A., & Lester, P. J. (2017). A metatranscriptomic survey of the invasive yellow crazy ant, Anoplolepis gracilipes, identifies several potential viral and bacterial pathogens and mutualists. Insectes Sociaux, 64(2), 197– 207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00040-016-0531-x

-

Cremer, S., Armitage, S. A. O., & Schmid-Hempel, P. (2007). Social immunity. Current Biology, 17(16), R693– R702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2007.06.008

-

Giehr, J., & Heinze, J. (2018). Queens stay, workers leave: Caste-specific responses to fatal infections in an ant. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 18(1), 202. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-018-1320-0

-

Gruber, M. A. M., Cooling, M., Baty, J. W., Buckley, K., Friedlander, A., Quinn, O., Russell, J. F. E. J., Sébastien, A., & Lester, P. J. (2017). Single-stranded RNA viruses infecting the invasive Argentine ant, Linepithema humile. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 3304. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-03508-z

-

Käfer, S., Paraskevopoulou, S., Zirkel, F., Wieseke, N., Donath, A., Petersen, M., Jones, T. C., Liu, S., Zhou, X., Middendorf, M., Junglen, S., Misof, B., & Drosten, C. (2019). Re-assessing the diversity of negative strand RNA viruses in insects. PLoS Path, 15(12), e1008224. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1008224

-

Keller, L., & Ross, K. G. (1993). Phenotypic plasticity and “cultural transmission” of alternative social organizations in the fire ant Solenopsis invicta. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 33(2), 121– 129. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00171663

-

Levitt, A. L., Singh, R., Cox-Foster, D. L., Rajotte, E., Hoover, K., Ostiguy, N., & Holmes, E. C. (2013). Cross-species transmission of honey bee viruses in associated arthropods. Virus Research, 176(1–2), 232– 240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2013.06.013

-

Manfredini, F., Martinez-Ruiz, C., Wurm, Y., Shoemaker, D. W., & Brown, M. J. F. (2021). Social isolation and group size are associated with divergent gene expression in the brain of ant queens. Genes, Brain and Behavior. e12758. https://doi.org/10.1111/gbb.12758

-

Martinez-Ruiz, C., Pracana, R., Stolle, E., Paris, C. I., Nichols, R. A., & Wurm, Y. (2020). Genomic architecture and evolutionary antagonism drive allelic expression bias in the social supergene of red fire ants. eLife, 9, e55862. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.55862

-

McMahon, D. P., Fürst, M. A., Caspar, J., Theodorou, P., Brown, M. J. F., & Paxton, R. J. (2015). A sting in the spit: Widespread cross-infection of multiple RNA viruses across wild and managed bees. Journal of Animal Ecology, 84(3), 615– 624. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.12345

-

Morandin, C., Tin, M. M. Y., Abril, S., Gómez, C., Pontieri, L., Schiøtt, M., Sundström, L., Tsuji, K., Pedersen, J. S., Helanterä, H., & Mikheyev, A. S. (2016). Comparative transcriptomics reveals the conserved building blocks involved in parallel evolution of diverse phenotypic traits in ants. Genome Biology, 17(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-016-0902-7

-

Nunn, C. L., Jordán, F., McCabe, C. M., Verdolin, J. L., & Fewell, J. H. (2015). Infectious disease and group size: More than just a numbers game. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 370(1669), 20140111. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2014.0111

-

Pracana, R., Levantis, I., Martínez-Ruiz, C., Stolle, E., Priyam, A., & Wurm, Y. (2017). Fire ant social chromosomes: Differences in number, sequence and expression of odorant binding proteins. Evolution Letters, 1(4), 199– 210. https://doi.org/10.1002/evl3.22

-

Pracana, R., Priyam, A., Levantis, I., Nichols, R. A., & Wurm, Y. (2017). The fire ant social chromosome supergene variant Sb shows low diversity but high divergence from SB. Molecular Ecology, 26(11), 2864– 2879. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.14054

-

Reber, A., Castella, G., Christe, P., & Chapuisat, M. (2008). Experimentally increased group diversity improves disease resistance in an ant species. Ecology Letters, 11(7), 682– 689. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01177.x

-

Ross, K. G. (1993). The breeding system of the fire ant Solenopsis invicta: Effects on colony genetic structure. The American Naturalist, 141(4), 554– 576. https://doi.org/10.1086/285491

-

Ross, K. G., & Keller, L. (1996). Ecology and evolution of social organization: Insights from fire ants and other highly eusocial insects. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 26, 631– 656.

-

Schläppi, D., Lattrell, P., Yañez, O., Chejanovsky, N., & Neumann, P. (2019). Foodborne transmission of deformed wing virus to ants (Myrmica rubra). Insects, 10(11), 394. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects10110394

-

Schmid-Hempel, P. (2017). Parasites and their social hosts. Trends in Parasitology, 33(6), 453– 462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2017.01.003

-

Schwenke, R. A., Lazzaro, B. P., & Wolfner, M. F. (2016). Reproduction–immunity trade-offs in insects. Annual Review of Entomology, 61(1), 239– 256. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-010715-023924

-

Sébastien, A., Lester, P. J., Hall, R. J., Wang, J., Moore, N. E., & Gruber, M. A. M. (2015). Invasive ants carry novel viruses in their new range and form reservoirs for a honeybee pathogen. Biology Letters, 11(9), 20150610. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2015.0610

-

Steinhauer, N., Kulhanek, K., Antúnez, K., Human, H., Chantawannakul, P., Chauzat, M.-P., & vanEngelsdorp, D. (2018). Drivers of colony losses. Current Opinion in Insect Science, 26, 142– 148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cois.2018.02.004

-

Stolle, E., Pracana, R., Howard, P., Paris, C. I., Brown, S. J., Castillo-Carrillo, C., Rossiter, S. J., & Wurm, Y. (2019). Degenerative expansion of a young supergene. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 36(3), 553– 561. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy236

-

Tschinkel, W. R. (2006). The fire ants. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

-

Valles, S. M. (2012). Positive-strand RNA viruses infecting the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. Psyche: A Journal of Entomology, 2012, 1– 14. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/821591

-

Valles, S. M., Oi, D. H., & Porter, S. D. (2010). Seasonal variation and the co-occurrence of four pathogens and a group of parasites among monogyne and polygyne fire ant colonies. Biological Control, 54, 342– 348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2010.06.006

-

Valles, S. M., & Porter, S. D. (2003). Identification of polygyne and monogyne fire ant colonies (Solenopsis invicta) by multiplex PCR of Gp-9 alleles. Insectes Sociaux, 50(2), 199– 200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00040-003-0662-8

-

Valles, S. M., & Rivers, A. R. (2019). Nine new RNA viruses associated with the fire ant Solenopsis invicta from its native range. Virus Genes, 55(3), 368– 380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11262-019-01652-4

-

van Baalen, M., & Beekman, M. (2006). The costs and benefits of genetic heterogeneity in resistance against parasites in social insects. The American Naturalist, 167(4), 568– 577. https://doi.org/10.1086/501169

-

Vander Meer, R. K., Obin, M. S., & Morel, L. (1990). Nestmate recognition in fire ants: Monogyne and polygyne populations. In R. K. Vander Meer, K. Jaffe & A. Cedeno, Applied Myrmecology: A world perspective. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press.

-

Vargo, E. L. (1992). Mutual pheromonal inhibition among queens in polygyne colonies of the fire ant Solenopsis invicta. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 31(3), 205– 210. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00168648

-

Vogel, V., Pedersen, J. S., d’Ettorre, P., Lehmann, L., & Keller, L. (2009). Dynamics and genetic structure of Argentine ant supercolonies in their native range. Evolution, 63(6), 1627– 1639. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00628.x

-

Wang, J., Wurm, Y., Nipitwattanaphon, M., Riba-Grognuz, O., Huang, Y.-C., Shoemaker, D., & Keller, L. (2013). A Y-like social chromosome causes alternative colony organization in fire ants. Nature, 493(7434), 664– 668. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11832

-

Wood, D. E., Lu, J., & Langmead, B. (2019). Improved metagenomic analysis with Kraken2. Genome Biology, 20(1), 257. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-019-1891-0

-

Wurm, Y., Wang, J., Riba-Grognuz, O., Corona, M., Nygaard, S., Hunt, B. G., Ingram, K. K., Falquet, L., Nipitwattanaphon, M., Gotzek, D., Dijkstra, M. B., Oettler, J., Comtesse, F., Shih, C.-J., Wu, W.-J., Yang, C.-C., Thomas, J., Beaudoing, E., Pradervand, S., … Keller, L. (2011). The genome of the fire ant Solenopsis invicta. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(14), 5679– 5684. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1009690108

-

Xavier, C. A. D., Allen, M. L., & Whitfield, A. E. (2021). Ever-increasing viral diversity associated with the red imported fire ant Solenopsis invicta (Formicidae: Hymenoptera). Virology Journal, 18(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-020-01469-w