Ants, Bees, Genomes & Evolution @ Queen Mary University London

Published: 31 July 2020

Complexity of the social environment and behavioural plasticity drive divergent gene expression in the brain of ant queens

Fabio Manfredini, Carlos Martinez-Ruiz, Yannick Wurm, DeWayne Shoemaker, Mark J.F. Brown

Abstract

Social life and isolation pose a complex suite of challenges to organisms prompting significant changes in neural state. However, plasticity in how brains respond to social challenges remains largely unexplored. The fire ants Solenopsis invicta provide an ideal scenario for examining this. Fire ant queens may found colonies individually or in groups of up to 30 queens. Here, we artificially manipulated availability of nesting sites to test how the brain responds to social vs. solitary colony founding at two key timepoints, and to group size. The difference between group and single founding queens involves only 1 gene when behaviour is still plastic and queens can switch from one modality to another, while hundreds of genes are involved once behaviours are more canalized. Furthermore, we show that large groups lead to greater changes in gene expression than small groups, perhaps due to higher cognitive demands of a more complex social environment.

Introduction

The social environment comprises the whole suite of interactions that an individual experiences with conspecifics, and consequently is a major driver of structure and function in animal groups. The social environment can affect a broad range of phenotypic traits (reviewed in (Robinson, Fernald, & Clayton, 2008)), including behavioural repertoires, physiological responses, and changes at the molecular level (for example, gene expression (Oliveira et al., 2016; Taborsky, Tschirren, Meunier, & Aubin-Horth, 2013)). One key feature of the social environment is complexity (reviewed in (Peckre, Kappeler, & Fichtel, 2019)), though there is no general agreement on how this feature should be quantified. The most obvious approach is to directly link complexity to group size, with larger animal groups being viewed as more complex than smaller ones, as they offer the possibility for a broader range of interactions among individuals (reviewed in (Kappeler, 2019)). However, group size alone is not a sufficient descriptor of complexity, as structural differences, in dominance hierarchies, numbers of breeders, etc., also impact group complexity (reviewed in (Kappeler, Clutton-Brock, Shultz, & Lukas, 2019)). Furthermore, it is not clear where groups of size equal to one (social isolation) should be placed in this framework. In principle, isolation is at the opposite side of the social spectrum compared to large social groups, and therefore should have no complexity at all. Nevertheless, it has been reported that social isolation can trigger very powerful responses at multiple levels, similarly to complex social environments (Fowler, Liu, Ouimet, & Wang, 2002). For example, isolation can have a significant impact on the brain, affecting neuron density (Y Pan, Li, Lieberwirth, Wang, & Zhang, 2014), gene expression (Bibancos, Jardim, Aneas, & Chiavegatto, 2007) and important biological functions such as stress response, endocrine regulation and locomotion (Yongliang Pan, Liu, Young, Zhang, & Wang, 2009).

From a behavioural point of view, the brain is the first organ that responds to the social environment (reviewed in (Oliveira, 2009)). The social environment during development can shape brain structure and functions in multiple ways (Fischer, Bessert-Nettelbeck, Kotrschal, & Taborsky, 2015), while social complexity correlates with brain power (Sobrero et al., 2016). This latter ”social brain hypothesis” (Robin I M Dunbar & Shultz, 2007) postulates that because life in social groups of different size poses different cognitive challenges, members of large groups should have more brain power, in particular when groups are stable. This theory has been mainly tested in vertebrates, with great success in primates (R I M Dunbar, 2018) but also some disagreement in other mammals (e.g. hyenas (Sakai, Arsznov, Lundrigan, & Holekamp, 2011)) and birds (e.g. wood-peckers (Fedorova, Evans, & Byrne, 2017)). However, it remains to be tested whether the social environment shapes brain capacity within the same species, where social groups can differ in size (but social structure and genetic background are the same) and are not stable, and hence the behaviours displayed are characterized by high amount of plasticity (see (Bshary & Oliveira, 2015) and (Gubert & Hannan, 2019)). Furthermore, brain size is just one way to measure brain power in animals and it is not necessarily the most accurate in all scenarios. Brain size is normally a good proxy for the number of neurons and the extent of the connections among them (but see (Herculano81 Houzel, 2009) for a full overview on this relationship): however, simple measures of brain size do not take into account how neurons function. For example, a study on macaques revealed that exposure to larger social networks promoted not only an increase of grey matter in specific areas of the brain, but also increased activity as measured via MRI scan (Sallet et al., 2011). It remains to be tested whether different conditions of the social environment affect brain functions at a molecular level, for example in terms of neuronal genes that are activated and repressed or key regulators that operate to drive complex transcriptomic changes.

Colony founding in fire ants represents an ideal scenario to address these questions. Newly mated queens of Solenopsis invicta can experience two drastically different social environments when setting up a new colony: total isolation, when a single queen relies exclusively on her own resources to produce the first generation of workers, or groupfounding, when multiple queens share the same nest (Walter R Tschinkel & Howard, 1983). In this second scenario, social groups can be of different size (from 2 to ~30) and provide the opportunity to explore the different social dynamics associated with small vs. large groups. Furthermore, colony founding in S. invicta is a dynamic process, characterized by 1) high plasticity at initiation, when queens normally move from nest to nest and can shift between single and group-founding strategies, and vice-versa; 2) a subsequent more stable phase of approximately 3-4 weeks, when behaviours are canalized (i.e., less susceptible to perturbations(Flatt, 2005)) within one of the two colony founding modalities (single vs. group) until the emergence of the first workers; and 3) a dramatic “conflict phase” in group-founding queens, that kicks in after worker emergence and terminates with the survival of only one queen in the colony, while all the others either leave the nest or are executed (Balas & Adams, 1996; Bernasconi & Keller, 1998; Bernasconi, Krieger, & Keller, 1997). Newly mated queens from the same ant population (and even from the same nest) can adopt either of the two modalities of colony founding. The “choice” appears to be influenced by the density of newly mated queens within a certain area and the availability of nesting sites (Walter R Tschinkel & Howard, 1983), hence there is no genetic pre-condition that drives this behaviour.

Here we used a powerful transcriptomic approach to explore global patterns of gene expression in the brains of S. invicta queens exposed to different social environments. We hypothesized that differences in the social environment will impose different demands on queens in terms of brain power that can be quantified as a measure of differential gene expression. We analyzed group-founding and single-founding queens in relation to queens that just returned from a mating flight, to explore how gene expression changes as a result of exposure to two drastically different social environments. Furthermore, we examined the impact of more subtle differences in the social environment, by performing a comparative analysis of large and small groups (i.e. 8-21 vs. 2-6 queens per group, respectively), to characterize gene expression patterns associated with different levels of social complexity. As large and small groups are formed by founding queens from the same population and experience the same social dynamics (e.g. proportions of breeders or ranges of social ranks within the group), we assumed that larger groups are more complex, as queens in these groups have the possibility to interact with a larger number of nestmates. Finally, in our comparative analysis of single and group founding queens we considered two timepoints, to understand how brain gene expression changes in association with different levels of behavioural plasticity. Specifically, we sampled queens at an early stage (3 days post-mating flight), when the modality of colony founding is still very plastic, and compared them to queens from a period (25 days post-mating flight) when behaviours are more canalized. We hypothesized that: 1) brain gene expression would largely respond to drastically different social environments (group vs. single-founding) and to a minor extent to similar social environments of different complexity (large vs. small social groups); 2) the neurogenomic signature associated with modality of colony founding would be stronger at the later stage of the process, when behaviours are more canalized, than at the early stage, when they are highly plastic; 3) more complex social environments (large groups) would be characterized by broader changes of brain gene expression compared to newly mated queens than less complex social environments (smaller groups).

Results and Discussion

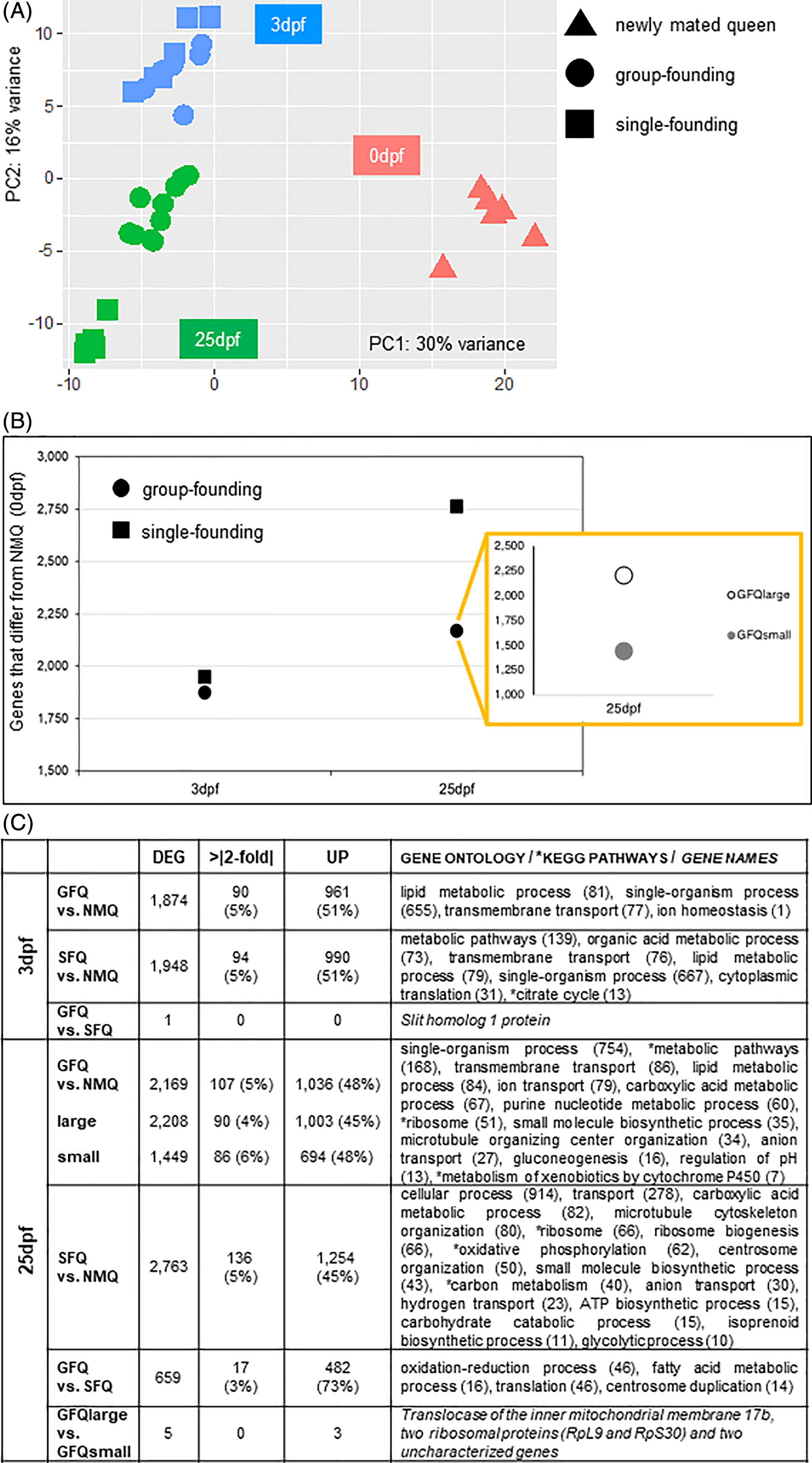

Expression profiles of grouped and single queens progressively diverge over time

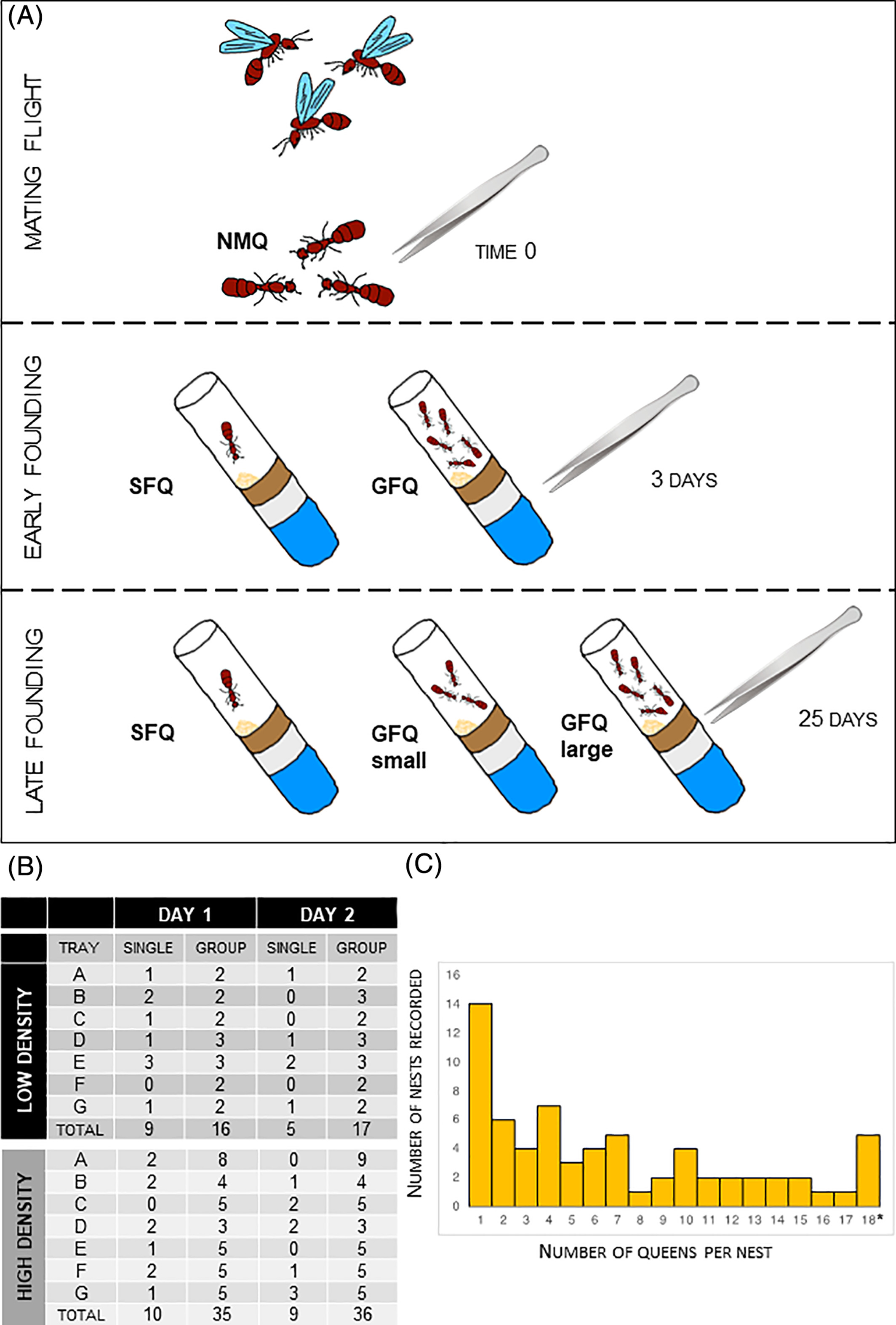

We performed a series of analyses to explore whether group-founding queens (GFQ) of the fire ant Solenopsis invicta differ from single-founding queens (SFQ) in their overall neurogenomic state (see FIG. 1 and method section for details on experimental design). We analyzed global patterns of gene expression in GFQ and SFQ across two time points that are key in the founding process: an early stage at 3 days post-founding (3dpf), when founding strategy is not yet fixed and queens can switch from GFQ to SFQ and vice-versa, and a late stage at 25 days post-founding (25dpf), when founding strategy is stable. We compared foundress queens to newly mated queens (NMQ) collected immediately after a mating flight and just before they started the process of founding a new colony: NMQ represent therefore the baseline or control group for brain gene expression in this study. Both groups of queens significantly differed from NMQ at both the early and late founding stages: PCA analysis revealed that 30% of global gene expression can be explained by differences between NMQ and all other queens (FIG. 2A). In line with this, hierarchical clustering analyses showed that NMQ are the outgroup in both analyses (supplementary figures). This clearly indicates that founding behaviour per se is the major driver of a queen’s neurogenomic state, while social environment associated with modality of colony founding and group size are only secondary. We also detected a general pattern of increasing differential expression over time in both groups of queens compared to NMQ; however, SFQ displayed a steeper increase than GFQ (FIG. 2B). To understand this pattern, we examined the difference between the two groups of queens and NMQ separately for each time point.

At 3dpf, both GFQ and SFQ differed from NMQ for similar numbers of genes, i.e., 1,874 and 1,948, respectively: the two sets both represent 13% of the total and are not significantly different in size (X2 test from equal: X2=0.72, df=1, P=0.40). The two sets also showed very similar proportions of genes that were more highly expressed and with expression levels higher than 2 folds compared to NMQ (FIG. 2C). Finally, they largely overlapped: 1,431 of the differentially expressed genes (>73% of the genes in either group) were shared across the two groups, a 5.7-fold higher proportion than expected by chance (Hypergeometric Test: P<0.001). These results clearly indicate that the difference between the neurogenomic states of GFQ and SFQ is minimal at 3dpf. This was supported by the fact that only one gene differed between GFQ and SFQ at this time point when we compared them directly (see FIG. 2C and further details below). We believe therefore that the behavioural plasticity of founding queens at 3dpf, when queens often move from nest to nest and possibly switch from GFQ to SFQ modality and vice-versa (FIG. 1B and (Walter R Tschinkel & Howard, 1983)), is reflected in their neurogenomic state. This means that their brain gene expression is not yet canalized, and maintains the plasticity to accommodate the two possible behavioural syndromes.

Later in the founding process the scenario visibly changed. In fact, at 25dpf, GFQ differed in brain gene expression from NMQ for 2,169 genes (15% of the total) while SFQ differed by 2,763 genes (19%): the difference between the sizes of the two gene sets is statistically significant (X2 test from equal: X2=35.90, df=1, P<0.01). This result holds even if we consider GFQlarge and GFQsmall separately (to keep sample size constant across groups, N=5): both the 2,208 genes that differed between GFQlarge and NMQ, and the 1,449 genes that differed between GFQsmall and NMQ were significantly smaller than the 2,763 genes that differed between SFQ and NMQ (X2 test from equal: X2=31.07 and X2=210.07, respectively, df=1, P<0.01). The two sets showed similar proportions of genes that were more highly expressed compared to NMQ and also the same proportion of genes with large fold changes compared to NMQ (FIG. 2C). PCA analysis supported the clear separation between GFQ and SFQ at 25dpf (FIG. 2A). It is clear that, at this stage of the founding process, the social environment that the queens experience affects their neurogenomic state to a larger extent than at 3dpf. This reflects their social history, with SFQ having spent 25 days in total isolation while GFQ were surrounded by a network of social interactions with nestmate queens. Furthermore, it is important to note that by 25dpf the behavioural plasticity that is typical of the first phase of the founding process is totally lost. SFQ no longer accept additional queens in the nest (they will aggressively reject them), while GFQ persist as social groups, which will transition to a phase of conflict later in the process of colony founding that will precipitate after the emergence of the first workers in the nest (Balas & Adams, 1996). Therefore, brain gene expression must be canalized in two different ways at this point: towards a linear monogyne social form of colony life in SFQ (one queen per colony) vs. more social dynamics (and conflict) in GFQ before monogyny is eventually reached.

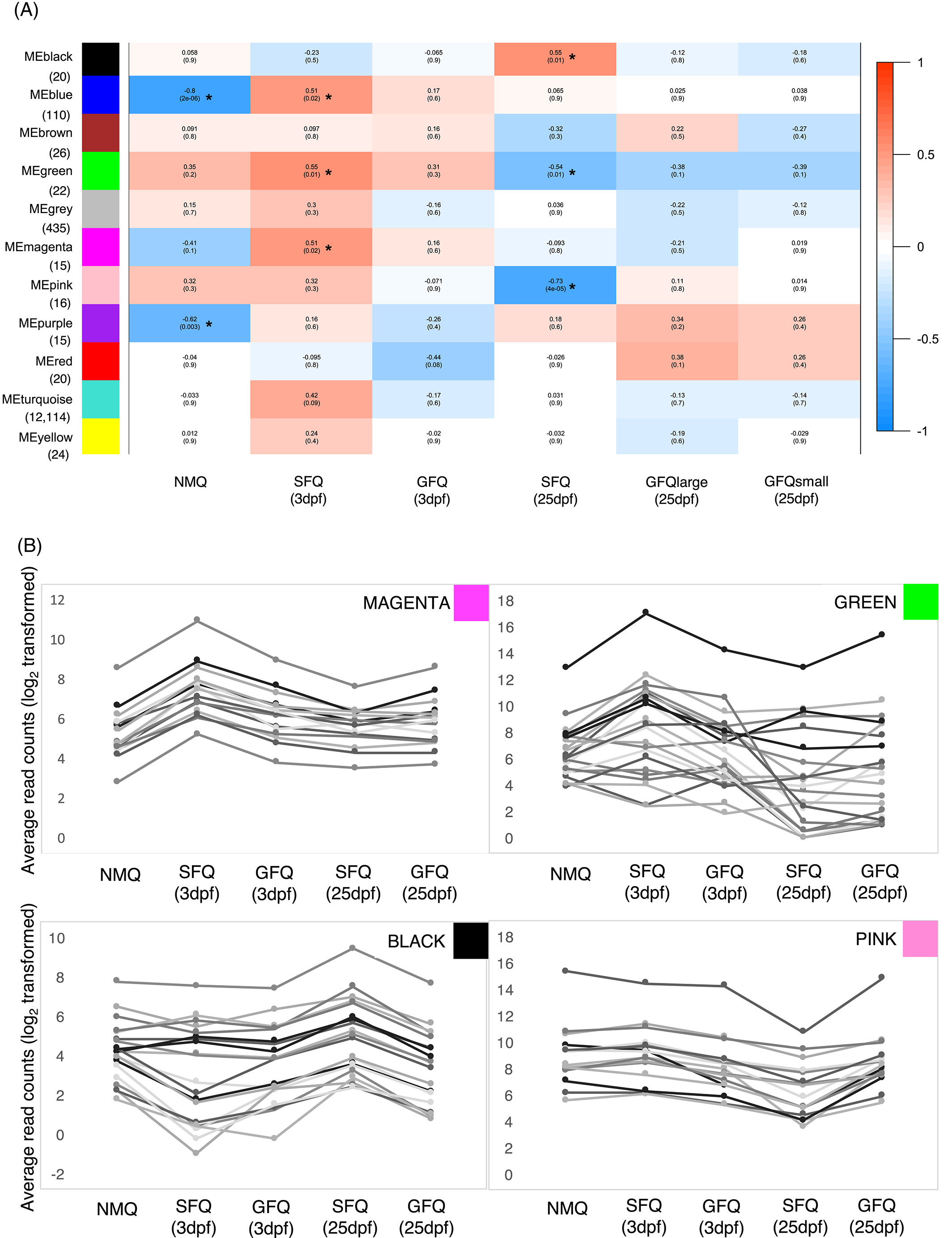

Specific brain gene sets exhibit differential expression in response to both isolation and prolonged exposure to social environments

We performed a second set of analyses to directly compare GFQ and SFQ and identify groups of genes that are significantly associated with group living vs. isolation. First, we built a global gene expression network, encompassing all 33 queens used for this study, and we identified network modules (groups of genes) that were significantly associated with GFQ or SFQ. Second, we performed direct pairwise comparisons between GFQ and SFQ at 3dpf and 25dpf, to characterize the key genes that were differentially expressed in the two groups of queens at the two time points.

Global gene network and module-trait association analyses. The fire ant brain gene network encompassed 11 modules (FIG. 3A), ranging in size from small (15 genes in the magenta and purple modules) to very large (12,114 genes in the turquoise module). No network modules were significantly associated with GFQ (P>0.05), whereas 5 modules were associated with SFQ (FIG. 3A and supplementary tables). Two modules (blue = 110 genes and magenta = 15 genes) were positively associated with SFQ at 3dpf, hence they represent sets of genes that quickly respond to early social isolation. Intriguingly, 10 of the 15 genes in the magenta module matched predicted S. invicta G-protein coupled receptors (key receptors of brain neural cells (Rosenbaum, Rasmussen, & Kobilka, 2009)) in the methuselah cluster (Mth-like, Mth-like 3 and Mth2-like), a group pf genes known to extend lifespan in Drosophila when less expressed (Paaby & Schmidt, 2009; Petrosyan, Gonçalves, Hsieh, & Saberi, 2014). There are nine Mth218 like receptors in S. invicta (Calkins, Tamborindeguy, & Pietrantonio, 2019), and four of these (Mth-like 1, 3, 5 and 10) were among the aging genes that were differentially expressed between single-founding and pair-founding queens in a previous microarray study (Manfredini et al., 2013). Our study supports the idea that social environment and ageing are tightly linked in fire ant founding queens, and showsthat the interaction is particularly evident in SFQ very early in the founding process, probably as a response to isolation.

Two modules (black = 20 genes and pink = 16 genes) were both associated with SFQ at 25dpf but in opposite directions: therefore, they both represent sets of genes that respond to long-term exposure to social isolation, but follow opposite patterns of expression (FIG. 3A and B). Several vision-related genes were included in this group: ninaA (LOC105194667), ninaC (LOC105200050), Arr1 (LOC105199319) and Arr2 (LOC105202669) all showed patterns of upregulation in SFQ at 25dpf (black module). Interestingly, the regulation of vision-related genes has been observed in other insects following mating and it has been linked to the switch from photophilic to photophobic behaviour (Dalton et al., 2010; Manfredini, Brown, Vergoz, & Oldroyd, 2015; Manfredini et al., 2017). Finally, Lsp1beta (LOC105192919, pink module) was less expressed in SFQ at 25dpf. This gene is a close relative of Lsp2, involved in synapse formation in Drosophila (Beneš et al., 1990) and it was more highly expressed in aggressive queens within founding pairs of the ant Pogonomyrmex californicus (Helmkampf, Mikheyev, Kang, Fewell, & Gadau, 2016).

A third network module (green = 22 genes) showed opposite patterns in SFQ at the two time points: in fact, it was positively associated with SFQ at 3dpf and negatively associated with SFQ at 25dpf (FIG. 3A and B). Hence, this small set of genes may play a role in the transition from incipient colony founding to colony establishment in SFQ, and might be responsible for the progressive canalization of gene expression that accompanies the loss of behavioural plasticity in SFQ as a consequence of social isolation. There was only one gene in the green module with known function in Drosophila: yolkless (LOC105200757), encoding the Vitellogenin receptor. Vitellogenin is an important reproductive protein in insects, responsible for the formation of the egg yolk (Tufail, Nagaba, Elgendy, & Takeda, 2014), but recent studies have linked the expression of vitellogenin in the insect head and brain to important social behaviours, like parental care or social aggression (Amdam, Norberg, Hagen, & Omholt, 2003; Manfredini, Brown, & Toth, 2018; Roy-Zokan, Cunningham, Hebb, McKinney, & Moore, 2015). If vitellogenin plays a role in the regulation of DNA functions in the insect brain, its expression in isolated queens could be the key mechanism of their behavioural response to social isolation. In addition, a group of genes in the green module are associated with chemical communication: the two putative odorant receptors 71a and 22c (LOC105206746 and LOC105206770, respectively), and three predicted odorant binding proteins (SiOBP3 LOC105194481; SiOBP4 LOC105194487; and SiOBP13 LOC105194495). Intriguingly, all three of these OBPs are located in the social chromosome “supergene” region that determines whether established colonies of this species accept multiple queens (Pracana, Levantis, et al., 2017; Pracana, Priyam, Levantis, Nichols, & Wurm, 2017). This prompted us to investigate whether genes in the supergene were overrepresented in the green module. This was the case for 6 of the 22 genes in the module, which is more than expected by chance (Fisher Test, P=0.002 after correction for multiple testing, supplementary tables and figures). This support the idea that such genes in the supergene region play important roles in shaping the queen’s reaction to her social environment. It is tempting to speculate for example that the variation in expression of such genes could affect the production or perception of odours of other queens within the nest.

Pairwise comparisons of gene expression. Expression of only 1 gene was significantly different between GFQ and SFQ at 3dpf and FDR<0.001: Slit homolog 1 protein (LOC105202267, 1.3 times higher in SFQ). Slit is associated with axon guidance, dendrite morphogenesis, neuron differentiation and migration in Drosophila (Brose et al., 1999). In the context of founding behaviour in fire ant queens, the fact that Slit is the one gene that differs between GFQ and SFQ (being more highly expressed in SFQ) suggests that future studies should explore its role in the process of brain restructuring caused by the lack of social interactions during isolation.

A much larger difference between GFQ and SFQ was observed at 25dpf, when 659 genes (4.5% of the total) significantly differed at FDR<0.001 (FIG. 2C). A large proportion of these genes (75%) was more highly expressed in GFQ, indicating that at this stage in the founding process life in social groups correlates with higher transcriptional activity of genes. As these measures were performed in the brain specifically, we hypothesize that group-living triggers higher neural response in fire ant queens than isolation. Interestingly, a study in guppies showed that exposure to a group of conspecifics activated a specific region of the forebrain when compared to social isolation (Cabrera-Álvarez, Swaney, & Reader, 2017). This activation, measured as increased expression of an immediate early gene (egr-1), was explained as a stimulation of the reward system in the fish brain due to the sight of conspecifics. A similar mechanism could be in place for GFQ in our study or, alternatively, increased gene expression could be explained by a release of inhibition in the regulation of large group of genes due to repeated social stimulation by nestmates. Further studies are needed in the future to test which, if any, of these hypotheses holds true.

The difference between GFQ and SFQ at 25dpf is also in line with a previous microarray study, where a large set of genes differed between single-founding queens and pair-founding queens sampled at a later stage in the founding process, when the conflict phase had already started among paired queens (3,192 genes at FDR<0.001 or 34% of the total analyzed (Manfredini et al., 2013)). Ageing is the most interesting process that was significantly overrepresented among genes that differed between GFQ and SFQ in our study (GO analyses, supplementary tables). Some of the genes in this group were also found in the microarray study(Manfredini et al., 2013), such as I’m not dead yet (LOC105193770), the superoxide dismutase genes Sod (LOC105208009) and Sod2 (LOC105203964), and the peroxiredoxin genes Prx3 (LOC105205792) and Prx5 (LOC105195487), similar to peroxiredoxins 6005 and 5037 from the microarray study. The fact that the same longevity genes also respond to social environments in other species (Parker, Parker, Sohal, Sohal, & Keller, 2004; Ruan & Wu, 2008; Wang et al., 2009) supports the hypothesis of a conserved function for these genes, which is also visible in fire ant queens. Here, the crosstalk between social environment and lifespan starts very early in the process of colony founding (3dpf) and continues for the whole duration, differentially affecting group-founding and single-founding queens. However, it remains unclear how exactly ageing genes and the social environment influence each other, and also how these dynamics evolve after the first workers emerge and the founding process terminates.

We explored the hypothesis that genes in the supergene region were overrepresented among genes that were differentially expressed between groups of queens. Of all pairwise comparisons, only GFQ vs. SFQ at 25dpf was significantly enriched for such genes, no matter whether groups were large or small (KS Test, P<0.05, supplementary tables). These results are in line with the output of the network module-trait association analysis, and further support the idea that the supergene region plays a role in the behavioural canalization that SFQ queens experience after prolonged exposure to social isolation.

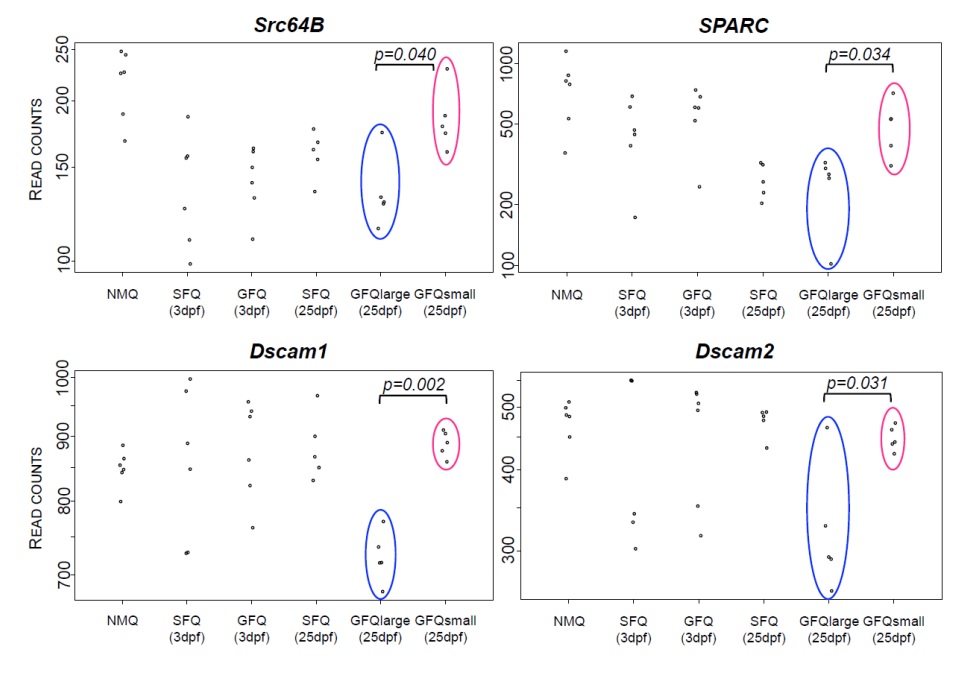

Large social groups trigger bigger changes in brain gene expression than small groups

Life in social groups of different size poses different cognitive challenges and it has been observed that members of large groups have more brain power, in particular when groups are stable (“social brain hypothesis” (Robin I M Dunbar & Shultz, 2007), but see (Fedorova et al., 2017)). To test this we compared gene expression in fire ant queens from large groups (GFQlarge, 8-21 queens per group) and small groups (GFQsmall, 2-6 queens) at 25dpf (FIG. 1). GFQlarge queens differed from NMQs for a larger number of brain genes compared to GFQsmall (2,208 and 1,409, respectively, at FDR<0.001, FIG. 2B inset and 2C), indicating that life in larger social groups is associated with the regulation of a significantly larger proportion of genes in the brain (X2 test from equal: X2=89.33, df=1, P<1e-5). We interpret these results at the molecular level as an indication that larger social groups are more cognitively demanding in fire ants, in agreement with the predictions of the “social brain hypothesis”. We must take into account, however, that gene expression is just the end product of transcription and different numbers of key regulators (e.g. transcription factors or non-coding RNA) could be associated with the two patterns that we observe. The possible role of transcriptional regulatory elements and their integration with gene-expression data surely deserve further investigation in the future (e.g. (Luscombe et al., 2004)).

A direct comparison of gene expression between GFQlarge and GFQsmall queens revealed that only 5 genes were significantly different at FDR<0.001 (FIG. 2C). However, a less stringent analysis (FDR<0.05) identified 258 genes that were different between the two groups. Many of these genes were significantly associated with behaviourally relevant functions (GO analyses, see supplementary tables) such as learning and memory with dunce (LOC105197141), neuralized (LOC105202574) and Pka-C1 (LOC105193172), neural functions with found in neurons (LOC105193515), foxo (LOC105196024), seven up(Kanai, Okabe, & Hiromi, 2005) (LOC105207607) and turtle (LOC105207535), and regulation of mRNA processing. The differential regulation of brain genes related to behavioural and neural functions supports the hypothesis that large groups differ from small groups in their cognitive demands, and also indicates that this difference might be associated with brain restructuring and protein synthesis leading to the formation of new synapses. Four genes in this group are of particular interest in the context of their potential role in the regulation of social behaviour in fire ant queens during colony founding (FIG. 4): Src64B (LOC105197191), Dscam1 (LOC105203138), Dscam2 (LOC105207772) and SPARC (LOC105197504). Src64B is a key regulator for the development of mushroom bodies, an important area in the insect brain responsible for the integration of a wide range of stimuli and usually associated with highly cognitive functions (Fahrbach, 2006). Levels of Src64B were 1.36 times higher in GFQsmall than in GFQlarge. Genes in the Dscam family are well known for their ability to generate many different protein isoforms through alternative splicing, and their function in the insect brain is linked to the formation of new neural connections (Tadros et al., 2016; Wojtowicz, Flanagan, Millard, Zipursky, & Clemens, 2004). Both Dscam1 and Dscam2 genes were more highly expressed in GFQsmall compared to GFQlarge (1.21 and 1.34 times higher, respectively). Finally, SPARC, known as the “gregarious specific gene” in locusts (Rahman et al., 2003) was more highly expressed in GFQsmall (1.81 times higher than in GFQlarge).

Conclusions

Through a series of brain gene expression and gene network analyses we show that the neurogenomic state of an insect responds to both drastic and subtle differences in social environment and reflects its complexity and plasticity. First, a major difference in the social environment (group living vs. isolation) is associated with significant proportions of genes that differ in their expression patterns. Second, we provide support for a link between behavioural plasticity and brain gene expression, showing that differences between neurogenomic states of grouped and single founding queens are minimal when behaviours are plastic (only one gene at 3dpf), but increase significantly when behaviours become canalized (hundreds of genes at 25dpf). Third, a much subtler difference in the social environment (large vs. small social groups) is still visible at the level of brain gene expression, with larger groups imposing bigger changes on the neurogenomic state, likely due to the higher cognitive costs associated with life in this type of social environment(Sandel et al., 2016).

These results clearly illustrate the power and high resolution of the neurogenomic approach, and also advocate for the necessity to add this perspective to more traditional approaches such as the analysis of brain allometry (e.g. (Finarelli & Flynn, 2009) and (O’Donnell & Bulova, 2017)) when investigating the levels of complexity in animal societies. There are also some evident limitations associated with transcriptomic studies overall, i.e. the impossibility to establish causative links between trait of interest and gene expression. In this study, for example, we cannot exclude that other pre-existing factors might be driving differential gene expression in GFQ vs. SFQ. As a matter of fact, we let queens opt for the modality of colony founding that they preferred at the beginning of our experiment, and this might have been dictated by some underlying conditions that we are unaware of. However, there are three considerations advocating for gene expression to be driven by social environment in this study: first, we collected queens from a homogeneous population with low genetic diversity, as indicated by the population’s history and genetic similarity of a sample from a previous year (see Methods) and also by the low rate of polyandry for fire ants colonies in the area (Lawson, vander Meer, & Shoemaker, 2012); second, GFQ at 25dpf (the group that mostly differed from isolated queens) derived from initial SFQ (see Methods), hence the only difference between GFQ and SFQ at this time point reflected the time spent in social groups vs. isolation; third, if there were pre-existing factors that differed among groups of queens they had no effect on brain gene expression, as clearly shown by the detection of only one differentially expressed gene between GFQ and SFQ at 3dpf.

This study shows the full potential of the neurogenomic approach to uncover the molecular underpinnings of a complex social behaviour that changes over time: highly plastic at the beginning, and more canalized later in the process. It would be interesting in the future to look at GFQ at the end of the conflict phase, when all other nestmate queens have been eliminated, to see whether plasticity is maintained and brain gene expression profiles transition back to an “isolation-like” phenotype comparable to the profile of SFQ – though the presence of workers in the colony at this stage might make it difficult to directly compare the two social environments. Our results lay the ground for future research aimed at characterizing the genes and genome functions that regulate key animal behaviours like cooperative founding, group living and social isolation.

Materials and Methods

Sample Collection and Housing

Newly mated queens of Solenopsis invicta were sampled on May 4th 403 2014 in a parking lot in Gainesville (Florida, USA, coordinates 29.6220°N, 82.3838°W) immediately after a big mating flight. This area is densely populated by monogyne colonies, as reported in the literature (Porter, 1992; Valles & Porter, 2003) and confirmed by the genotyping of newly mated queens collected in the same location in 2010 (98% prevalence of the Gp-9BB genotype (Manfredini, Shoemaker, & Grozinger, 2016)). Queens were individually collected with forceps directly from the tarmac and transferred to a small plastic cup (supplementary figures). All these queens were wingless, hence they had spent several minutes up to 2 hours on the tarmac looking for a suitable nesting site. In fact, within 2 hours from a mating flight all queens usually disappear from above ground in field observations (Walter Reinhart Tschinkel, 2006). A set of 34 queens was frozen on dry ice immediately after collection in the field. These are the newly mated queens group (from now on NMQ), which represents the baseline for gene expression analyses in this study.

The other queens were allowed to choose between two modalities of colony founding that are both recurrent in populations of S. invicta in the USA: single-founding (SF, 1 queen per nest, also called “haplometrosis”) or group-founding (GF, ≥ 2 queens per nest, also called “pleometrosis”). After a set of plastic cups (12 total) was completed, the queens were released in large trays containing nesting chambers (supplementary figures) where fire ant queens usually build their colony in lab conditions (Manfredini et al., 2013) . As the mode of colony founding in the field is density dependent (i.e., group-finding is more frequent when the rate of queen-queen encounters is higher (Walter R Tschinkel & Howard, 1983)), we used two different setups to promote spontaneous formation of SF and GF nests. We used lower density to promote SF: this consisted in releasing 24 queens in a large tray containing 24 nesting chambers (7 trays total). Conversely, we used higher density to promote GF associations: here 48 queens were released in a smaller tray containing only 14 nesting chambers (7 trays total). Ultimately, the proportion of nests that were SF was slightly higher for low-density groups as we expected (1/3 of the total vs. 1/4, FIG. 1B).

All 14 trays were transported to an environmental chamber were queens were reared in standard claustral conditions (no food, no water, in the dark). For the first 2 days, nesting chambers were left open so that queens could freely move from one chamber to another (mimicking what normally happens in the field). We recorded the numbers of SF and GF nests for both days (FIG. 1B). At the end of DAY 2, a good mix of different options for colony founding was reached, with many SF nests (N=14) and also GF nests of variable size (from 2 to 30, FIG. 1C). We transferred each nesting chamber to a separate pencil box so that queens were no longer allowed to move across nests. We kept queens in these conditions (claustral colony founding (Brown & Bonhoeffer, 2003)) until the emergence of workers (1 month approximately).

Experimental Design

Prior to allocating queens to experimental groups for RNA sequencing (RNAseq) we dissected abdomens to check the spermatheca for mating status and to look at ovary development. Only mated queens (visible spermatheca) that had fully developed eggs visible within their ovaries (see supplementary figures) were considered for this study. This step was performed to avoid any confounding effect of mating and reproductive status of queens on brain gene expression, as our aim was to focus specifically on gene expression associated with founding behaviour and type of social environment.

We performed a first RNAseq experiment to investigate the patterns of brain gene expression at an earlier stage of the founding process, i.e. 3 days. We included 3 groups of queens: 1) NMQ as a control/baseline group (N=6, randomly picked from the pool of queens that were frozen right after collection, after confirming mating status); 2) single-founding queens at 3 days post-founding (SFQ 3dpf, N=6); 3) group-founding queens at 3 days post454 founding (range 12-30 queens per group, see supplementary tables for details, GFQ 3dpf, N=6). In the second experiment, we analyzed queens at a later stage of the founding process, i.e. 25 days. Here we included 4 groups of queens: 1) the same NMQ for control/baseline; 2) single-founding queens sampled at 25 days post-founding (SFQ 25dpf, N=5); 3) group458 founding queens at 25 days post-founding from small groups (range 2-6 queens per group, see supplementary tables for details, GFQsmall 25dpf, N=5); 4) group-founding queens at 25 days post-founding from large groups (range 8-21 queens per group, see supplementary tables for details, GFQlarge 25dpf, N=5). For this experiment, SFQ were obtained from initial GF associations (range 7-11 queens per group) on day 4 post-founding. The only relevant difference was therefore that they spent 3 weeks in isolation vs. being in a small or large group. All queens from GFQ treatments that were used for these analyses came from different founding groups. No workers had emerged in any of the experimental colonies at the time of queen sampling.

Molecular Work for RNA Sequencing

All queens were flash frozen on dry ice and immediately transferred to a -80°C freezer for later processing. Frozen samples were shipped to Royal Holloway University of London where subsequent steps were performed. We placed individual heads on dry ice, we exposed the brain by gently scraping off the cuticle and other off-target layers (e.g. frozen haemolymph), and we removed both eyes, mouthparts and associated glands.

We isolated total RNA from individual brains following the same procedure as described in (Manfredini et al., 2017). We aimed to include only samples with total RNA > 200ng (based on a NanoDrop™ spectrophotometer instrument, ThermoFisher) and RIN value ≥ 7 (TapeStation System, Agilent Technolgies) in the RNAseq experiment. However, due to limitation in the number of replicates, we included 2 samples that had RIN value between 6 and 7 (see supplementary tables for full details on all samples included in the study). Subsequent steps were performed by Beckman Coulter Genomic (now GENEWIZ) at their facility in USA: this included cDNA synthesis, library preparation using the Illumina TruSeq Stranded Total RNA with Ribo‐Zero Kit, and sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform.

Analysis of Gene Expression

RNAseq read files were aligned to the S. invicta genome (assembly gnG, release 100 from refSeq) using the intron-aware STAR aligner, version 2.6.1a (Dobin et al., 2013). We followed two approaches: we first used the official geneset for the fire ant genome deposited on NCBI, and second we also performed an alignment to an enhanced geneset obtained with Cufflinks, version 2.2.1 (Trapnell et al., 2010) (reference annotation based transcript assembly). This second approach allowed us to include in the reference geneset real genes missing from the official geneset, missing exons of previously known genes, or background transcription. Following steps were performed in parallel so that in the end we could chose the first approach (NCBI based) that we deemed more suitable to perform analyses of differential gene expression.

Read counts were extracted using featureCounts, part of the Bioconductor R package Subread (Liao, Smyth, & Shi, 2019), version 1.5.2, and we generated a list of raw number reads per gene. Raw reads were normalized for sequencing depth and this output was used to calculate differential gene expression. This was done by combining two separate analyses for each of the two experiments: a likelihood ratio test to detect what genes were more differentially expressed across all levels (LRT approach); and planned pairwise comparisons between phenotypes of interest using the Bioconductor R package DESeq2, version 1.24 (Love, Huber, & Anders, 2014). In all analyses, differential expression was obtained by correcting for multiple testing with FDR (false-discovery rate). We used the whole set of normalized count data processed with DESeq2 to perform a Principal Component analysis, and we used the outputs of the LRT approaches to perform separate Hierarchical Clustering analyses for the two experiments. In this case, we used only the sets of genes that were differentially expressed at FDR<0.001 and we performed a clustering analysis based on queen phenotypes.

Gene Ontology analyses were performed in DAVID Bioinformatics Resources 6.8 (Huang, Sherman, & Lempicki, 2009) using Drosophila orthologues for S. invicta genes. We performed Functional Annotation Clustering to group together related GO terms (Biological Processes only) or KEGG pathways, and we identify significantly enriched terms using a threshold of p-value<0.05 plus a correction factor using Benjamini=0.05.

Weighed gene-coexpression network analysis was performed on all 33 queens included in this study using the R package WGCNA (Langfelder & Horvath, 2008), version 1.68, and with a soft-threshold power of 12. This value was chosen among a series of outputs as it was the closest to produce an R^2 value of 0.85 (normally recommended as an ideal target by the software developer in order to guarantee a scale-free network). Module-trait association analyses were performed in R, following the same approach as described in (Manfredini et al., 2017). Briefly, we performed a correlation test using the “cor” function in R and we adopted a threshold for signification correlation of 0.05 after Benjamini-Hochberg correction. We correlated module eigengenes with “trait values” represented by each group of queens considered in this study, i.e. NMQ, SFQ 3dpf and 25dpf, GFQ 3dpf, GFQlarge and GFQsmall 25dpf. We also performed an additional WGCNA analysis where we compared two separate networks, one built on data from all GFQ and another one based on SFQ data. We are aware that sample size for this comparative analysis is limited as the number of individuals per network was below 20. We decide therefore not to include this analysis in the main text, but see supplementary information for details on how this analysis was performed and relative outputs.

Gene enrichment analyses for elements of the supergene region were performed in R using two approaches. First, we performed an “enrichment per module” analysis, where we checked whether any of the modules obtained through the network analysis had more supergene loci than expected by chance. We used a Fisher test to verify whether the expected ratio of supergene elements was observed in each module based on what we observe at the level of the whole genome (640 genes in the supergene and 13973 outside (Pracana, Levantis, et al., 2017)). As a second approach, we performed an “enrichment for differentially expressed genes” analysis, to test whether supergene elements were overrepresented among differentially expressed genes for each pairwise comparison. For this we used a Kolmogorov Smirnoff test to compare the distribution of uncorrected P values between supergene and non-supergene loci per comparison.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank members of the Shoemaker’s Lab at the USDA-ARS in Gainesville for support during field experiments and sample collections: special thanks to Eileen Carroll who coordinated all activities associated with field experiments and arranged the shipment of samples to the UK. The authors would also like to thank all members of the Leadbeater Lab at Royal Holloway for providing feedback on an early draft of this manuscript. This work was supported by a Marie Curie International Incoming Fellowship (FP7-PEOPLE549 2013-IIF-625487) to F.M. and M.J.F.B. which also supported F.M. salary for two years. The Natural Environment Research Council supported the salaries of C.M.R. (NE/L002485/1) and Y.W. (NE/L00626X/1).

References

-

Amdam, G. v, Norberg, K., Hagen, A., & Omholt, S. W. (2003). Social exploitation of vitellogenin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(4), 1799–1802.

-

Balas, M. T., & Adams, E. S. (1996). The dissolution of cooperative groups: mechanisms of queen mortality in incipient fire ant colonies. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 38(6), 391–399.

-

Beneš, H., Edmondson, R. G., Fink, P., Kejzlarová-Lepesant, J., Lepesant, J.-A., Miles, J. P., & Spivey, D. W. (1990). Adult expression of the Drosophila Lsp-2 gene. Developmental Biology, 142(1), 138–146.

-

Bernasconi, G., & Keller, L. (1998). Phenotype and individual investment in cooperative foundress associations of the fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. Behavioral Ecology, 9(5), 478–485.

-

Bernasconi, G., Krieger, M. J. B., & Keller, L. (1997). Unequal partitioning of reproduction and investment between cooperating queens in the fire ant, Solenopsis invicta, as revealed by microsatellites. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 264(1386), 1331–1336.

-

Bibancos, T., Jardim, D. L., Aneas, I., & Chiavegatto, S. (2007). Social isolation and expression of serotonergic neurotransmission‐related genes in several brain areas of male mice. Genes, Brain and Behavior, 6(6), 529–539.

-

Brose, K., Bland, K. S., Wang, K. H., Arnott, D., Henzel, W., Goodman, C. S., … Kidd, T. (1999). Slit proteins bind Robo receptors and have an evolutionarily conserved role in repulsive axon guidance. Cell, 96(6), 795–806.

-

Brown, M. J. F., & Bonhoeffer, S. (2003). On the evolution of claustral colony founding in ants. Evolutionary Ecology Research, 5(2), 305–313.

-

Bshary, R., & Oliveira, R. F. (2015). Cooperation in animals: toward a game theory within the framework of social competence. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 3, 31–37.

-

Cabrera-Álvarez, M. J., Swaney, W. T., & Reader, S. M. (2017). Forebrain activation during social exposure in wild-type guppies. Physiology & Behavior, 182, 107–113.

-

Calkins, T. L., Tamborindeguy, C., & Pietrantonio, P. v. (2019). GPCR annotation, G proteins, and transcriptomics of fire ant (Solenopsis invicta) queen and worker brain: An improved view of signaling in an invasive superorganism. General and Comparative Endocrinology, 278, 89–103.

-

Dalton, J. E., Kacheria, T. S., Knott, S. R. v, Lebo, M. S., Nishitani, A., Sanders, L. E., … Arbeitman, M. N. (2010). Dynamic, mating-induced gene expression changes in female head and brain tissues of Drosophila melanogaster. Bmc Genomics, 11(1), 541.

-

Dobin, A., Davis, C. A., Schlesinger, F., Drenkow, J., Zaleski, C., Jha, S., … Gingeras, T. R. (2013). STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics, 29(1), 15–21.

-

Dunbar, R I M. (2018). Social structure as a strategy to mitigate the costs of group living: a comparison of gelada and guereza monkeys. Animal Behaviour, 136, 53–64.

-

Dunbar, Robin I M, & Shultz, S. (2007). Evolution in the social brain. Science, 317(5843), 1344–1347.

-

Fahrbach, S. E. (2006). Structure of the mushroom bodies of the insect brain. Annu. Rev. Entomol., 51, 209–232.

-

Fedorova, N., Evans, C. L., & Byrne, R. W. (2017). Living in stable social groups is associated with reduced brain size in woodpeckers (Picidae). Biology Letters, 13(3), 20170008.

-

Finarelli, J. A., & Flynn, J. J. (2009). Brain-size evolution and sociality in Carnivora. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(23), 9345–9349.

-

Fischer, S., Bessert-Nettelbeck, M., Kotrschal, A., & Taborsky, B. (2015). Rearing-group size determines social competence and brain structure in a cooperatively breeding cichlid. The American Naturalist, 186(1), 123–140.

-

Flatt, T. (2005). The evolutionary genetics of canalization. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 80(3), 287–316.

-

Fowler, C. D., Liu, Y., Ouimet, C., & Wang, Z. (2002). The effects of social environment on adult neurogenesis in the female prairie vole. Journal of Neurobiology, 51(2), 115–128.

-

Gubert, C., & Hannan, A. J. (2019). Environmental enrichment as an experience-dependent modulator of social plasticity and cognition. Brain Research.

-

Helmkampf, M., Mikheyev, A. S., Kang, Y., Fewell, J., & Gadau, J. (2016). Gene expression and variation in social aggression by queens of the harvester ant Pogonomyrmex californicus. Molecular Ecology, 25(15), 3716–3730.

-

Herculano-Houzel, S. (2009). The human brain in numbers: a linearly scaled-up primate brain. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 3, 31.

-

Huang, D. W., Sherman, B. T., & Lempicki, R. A. (2009). Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nature Protocols, 4(1), 44.

-

Kanai, M. I., Okabe, M., & Hiromi, Y. (2005). seven-up Controls switching of transcription factors that specify temporal identities of Drosophila neuroblasts. Developmental Cell, 8(2), 203–213.

-

Kappeler, P. M. (2019). A framework for studying social complexity. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 73(1), 13.

-

Kappeler, P. M., Clutton-Brock, T., Shultz, S., & Lukas, D. (2019). Social complexity: patterns, processes, and evolution. Springer. Langfelder, P., & Horvath, S. (2008). WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics, 9(1), 559.

-

Lawson, L. P., vander Meer, R. K., & Shoemaker, D. (2012). Male reproductive fitness and queen polyandry are linked to variation in the supergene Gp-9 in the fire ant Solenopsis invicta. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 279(1741), 3217–3222.

-

Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K., & Shi, W. (2019). The R package Rsubread is easier, faster, cheaper and better for alignment and quantification of RNA sequencing reads. Nucleic Acids Research, 47(8), e47–e47.

-

Love, M. I., Huber, W., & Anders, S. (2014). Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biology, 15(12), 550.

-

Luscombe, N. M., Babu, M. M., Yu, H., Snyder, M., Teichmann, S. A., & Gerstein, M. (2004). Genomic analysis of regulatory network dynamics reveals large topological changes. Nature, 431(7006), 308–312.

-

Manfredini, F., Brown, M. J. F., & Toth, A. L. (2018). Candidate genes for cooperation and aggression in the social wasp Polistes dominula. Journal of Comparative Physiology A, 204(5), 449–463.

-

Manfredini, F., Brown, M. J. F., Vergoz, V., & Oldroyd, B. P. (2015). RNA-sequencing elucidates the regulation of behavioural transitions associated with the mating process in honey bee queens. BMC Genomics, 16(1), 563.

-

Manfredini, F., Riba-Grognuz, O., Wurm, Y., Keller, L., Shoemaker, D., & Grozinger, C. M. (2013). Sociogenomics of cooperation and conflict during colony founding in the fire ant Solenopsis invicta. PLoS Genetics, 9(8).

-

Manfredini, F., Romero, A. E., Pedroso, I., Paccanaro, A., Sumner, S., & Brown, M. J. F. (2017). Neurogenomic signatures of successes and failures in life-history transitions in a key insect pollinator. Genome Biology and Evolution, 9(11), 3059–3072.

-

anfredini, F., Shoemaker, D., & Grozinger, C. M. (2016). Dynamic changes in host–virus interactions associated with colony founding and social environment in fire ant queens (Solenopsis invicta). Ecology and Evolution, 6(1), 233–244.

-

O’Donnell, S., & Bulova, S. (2017). Development and evolution of brain allometry in wasps (Vespidae): size, ecology and sociality. Current Opinion in Insect Science, 22, 54–61.

-

Oliveira, R. F. (2009). Social behavior in context: hormonal modulation of behavioral plasticity and social competence. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 49(4), 423–440.

-

Oliveira, R. F., Simões, J. M., Teles, M. C., Oliveira, C. R., Becker, J. D., & Lopes, J. S. (2016). Assessment of fight outcome is needed to activate socially driven transcriptional changes in the zebrafish brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(5), E654–E661.

-

Paaby, A. B., & Schmidt, P. S. (2009). Dissecting the genetics of longevity in Drosophila melanogaster. Fly, 3(1), 29–38.

-

Pan, Y, Li, M., Lieberwirth, C., Wang, Z., & Zhang, Z. (2014). Social defeat and subsequent isolation housing affect behavior as well as cell proliferation and cell survival in the brains of male greater long-tailed hamsters. Neuroscience, 265, 226–237.

-

Pan, Yongliang, Liu, Y., Young, K. A., Zhang, Z., & Wang, Z. (2009). Post-weaning social isolation alters anxiety-related behavior and neurochemical gene expression in the brain of male prairie voles. Neuroscience Letters, 454(1), 67–71.

-

Parker, J. D., Parker, K. M., Sohal, B. H., Sohal, R. S., & Keller, L. (2004). Decreased expression of Cu–Zn superoxide dismutase 1 in ants with extreme lifespan. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 101(10), 3486–3489.

-

Peckre, L., Kappeler, P. M., & Fichtel, C. (2019). Clarifying and expanding the social complexity hypothesis for communicative complexity. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 73(1), 11.

- Petrosyan, A., Gonçalves, Ó. F., Hsieh, I.-H., & Saberi, K. (2014). Improved functional abilities of the life-extended Drosophila mutant Methuselah are reversed at old age to below control levels. Age, 36(1), 213–221.

-

Porter, S. D. (1992). Frequency and distribution of polygyne fire ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Florida. Florida Entomologist, 248–257.

-

Pracana, R., Levantis, I., Martínez‐Ruiz, C., Stolle, E., Priyam, A., & Wurm, Y. (2017). Fire ant social chromosomes: Differences in number, sequence and expression of odorant binding proteins. Evolution Letters, 1(4), 199–210.

-

Pracana, R., Priyam, A., Levantis, I., Nichols, R. A., & Wurm, Y. (2017). The fire ant social chromosome supergene variant Sb shows low diversity but high divergence from SB. Molecular Ecology, 26(11), 2864–2879.

-

Rahman, M. M., Vandingenen, A., Begum, M., Breuer, M., de Loof, A., & Huybrechts, R. (2003). Search for phase specific genes in the brain of desert locust, Schistocerca gregaria (Orthoptera: Acrididae) by differential display polymerase chain reaction. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology, 135(2), 221–228.

-

Robinson, G. E., Fernald, R. D., & Clayton, D. F. (2008). Genes and social behavior. Science, 322(5903), 896–900.

-

Rosenbaum, D. M., Rasmussen, S. G. F., & Kobilka, B. K. (2009). The structure and function of G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature, 459(7245), 356–363.

-

Roy-Zokan, E. M., Cunningham, C. B., Hebb, L. E., McKinney, E. C., & Moore, A. J. (2015). Vitellogenin and vitellogenin receptor gene expression is associated with male and female parenting in a subsocial insect. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 282(1809), 20150787.

-

Ruan, H., & Wu, C.-F. (2008). Social interaction-mediated lifespan extension of Drosophila Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase mutants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(21), 7506–7510.

-

Sakai, S. T., Arsznov, B. M., Lundrigan, B. L., & Holekamp, K. E. (2011). Brain size and social complexity: a computed tomography study in hyaenidae. Brain, Behavior and Evolution, 77(2), 91–104.

-

Sallet, J., Mars, R. B., Noonan, M. P., Andersson, J. L., O’reilly, J. X., Jbabdi, S., … Rushworth, M. F. S. (2011). Social network size affects neural circuits in macaques. Science, 334(6056), 697–700.

-

Sandel, A. A., Miller, J. A., Mitani, J. C., Nunn, C. L., Patterson, S. K., & Garamszegi, L. Z. (2016). Assessing sources of error in comparative analyses of primate behavior: Intraspecific variation in group size and the social brain hypothesis. Journal of Human Evolution, 94, 126–133.

-

Sobrero, R., Fernández-Aburto, P., Ly-Prieto, Á., Delgado, S. E., Mpodozis, J., & Ebensperger, L. A. (2016). Effects of habitat and social complexity on brain size, brain asymmetry and dentate gyrus morphology in two octodontid rodents. Brain, Behavior and Evolution, 87(1), 51–64.

-

Taborsky, B., Tschirren, L., Meunier, C., & Aubin-Horth, N. (2013). Stable reprogramming of brain transcription profiles by the early social environment in a cooperatively breeding fish. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 280(1753), 20122605.

-

Tadros, W., Xu, S., Akin, O., Caroline, H. Y., Shin, G. J., Millard, S. S., & Zipursky, S. L. (2016). Dscam proteins direct dendritic targeting through adhesion. Neuron, 89(3), 480–493.

-

Trapnell, C., Williams, B. A., Pertea, G., Mortazavi, A., Kwan, G., van Baren, M. J., … Pachter, L. (2010). Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nature Biotechnology, 28(5), 511.

-

Tschinkel, Walter R, & Howard, D. F. (1983). Colony founding by pleometrosis in the fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 12(2), 103–113.

-

Tschinkel, Walter Reinhart. (2006). The fire ants. Harvard University Press. Tufail, M., Nagaba, Y., Elgendy, A. M., & Takeda, M. (2014). Regulation of vitellogenin genes in insects. Entomological Science, 17(3), 269–282.

-

Valles, S. M., & Porter, S. D. (2003). Identification of polygyne and monogyne fire ant colonies (Solenopsis invicta) by multiplex PCR of Gp-9 alleles. Insectes Sociaux, 50(2), 199–200.

-

Wang, P.-Y., Neretti, N., Whitaker, R., Hosier, S., Chang, C., Lu, D., … Helfand, S. L. (2009). Long-lived Indy and calorie restriction interact to extend life span. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(23), 9262–9267.

- Wojtowicz, W. M., Flanagan, J. J., Millard, S. S., Zipursky, S. L., & Clemens, J. C. (2004). Alternative splicing of Drosophila Dscam generates axon guidance receptors that exhibit isoform-specific homophilic binding. Cell, 118(5), 619–633.

Data Availability

RNAseq data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in NCBI BioProject Submissions with the SubmissionID: SUB5134076s and BioProject ID: PRJNA525584 https://submit.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/subs/bioproject/SUB5134076/overview. All other data and codes that are not included in the main text or supplementary materials are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: F.M. and M.J.F.B.; Methodology: F.M., C.M.R., Y.W., D.S. and M.J.F.B.; Software: C.M.R. and Y.W.; Formal Analysis: F.M. and C.M.R.; Investigation: F.M.; Resources: Y.W., D.S. and M.J.F.B.; Data Curation: F.M., C.M.R. and Y.W.; Writing – Original Draft: F.M. and M.J.F.B.; Writing – Review & Editing: F.M., C.M.R., Y.W., D.S. and M.J.F.B.; Funding Acquisition: F.M. and M.J.F.B.

Supplementary Data

Figure 1

Experimental setup and sample collections. (A) Queens were sampled after a mating flight and reared in artificial nesting chambers in the lab. Focal queens were frozen at three key time points for RNA sequencing: 0, 3 and 25 days post-founding. (B) Numbers of individual queens and associations that were recorded during the first 2 days of the process when different availabilities of nesting sites were simulated: large trays with abundant nests (“low density” of queens) or small trays with fewer nests (“high density” of queens). (C) Proportions of individual queens and groups of different size that were observed at day 2 post-founding. Note: This category includes founding groups of 18 or more queens (maximum recorded = 30). GFQ, group-founding queens from small (2–6 queens) and large groups (8–21 queens); NMQ, newly mated queens; SFQ, single-founding queens

Figure 2

Gene expression analyses of group-founding versus single-founding queens. (A) Principal Component Analysis of all queen samples included in this study. The first component (30%) explains the difference between newly mated queens and all other groups of queens, while the second component (16%) explains the difference between the two time-points of collection for founding queens, that is, 3 and 25 days post-founding (3dpf and 25dpf, respectively). (B) Number of gene differentially expressed (FDR < 0.001) in group-founding queens and single-founding queens at 3 and 25 days post-founding. The inset shows the details of large and small groups at 25 days post-founding. Differentially expressed genes for all groups are calculated with respect to newly mated queens at time 0. (C) Summary table for gene expression data produced by all pairwise comparisons of interest. Only gene ontology terms and KEGG pathways that survived Benjamini correction (P-value < 0.05) are reported or, when only few genes were differentially expressed, genes names are indicated. DEG, significantly differentially expressed genes; dpf, days post-founding; GFQ, group-founding queens from small (2–6 queens) and large groups (8–21 queens); NMQ, newly mated queens, SFQ, single-founding queens; UP, upregulated

Figure 3

Weighed gene-coexpression network analysis. (A) Module-trait association analysis, showing what modules are significantly associated (*) with each group of queens. The matrix is color coded, with warm colors indicating positive associations (x-value > 0) and cold colors indicating negative associations. P-values corrected for multiple testing (Benjamini-Hochberg) are also indicated below. Below each module, in brackets, is indicated the total number of genes within the module. (B) Details of the patterns of expression in five groups of queens for all the genes included in four modules (magenta, green, black, and pink) that were significantly associated with single-founding behavior. Raw data for the genes in each module are available in Dataset S4. dpf, days post-founding; GFQ, group-founding queens from small (2–6 queens) and large groups (8–21 queens); ME, module eigenvalue; NMQ, newly mated queens; SFQ, single-founding queens

Figure 4

Gene expression analysis of large vs. small groups. Normalized read counts for 4 genes that differed between GFQlarge and GFQsmall and are particularly interesting for their role in cognition and neural functions. Read counts are plotted according to the 6 different groups of queens considered in this study.