Ants, Bees, Genomes & Evolution @ Queen Mary University London

Published: 29 September 2021

Functional genomics of supergene-controlled behavior in the white-throated sparrow

Peter WH Holland, Chris D Jiggins, Miriam Liedvogel, Graham Warren, Yannick Wurm

Faculty Reviews (2021)

Abstract

Supergenes are regions of suppressed recombination that may span hundreds of genes and can control variation in key ecological phenotypes. Since genetic analysis is made impossible by the absence of recombination between genes, it has been difficult to establish how individual genes within these regions contribute to supergene-controlled phenotypes. The white-throated sparrow is a classic example in which a supergene controls behavioral differences as well as distinct coloration that determines mate choice. A landmark study now demonstrates that differences between supergene variants in the promoter sequences of a hormone receptor gene change its expression and control changes in behavior. To unambiguously establish the link between genotype and phenotype, the authors used antisense oligonucleotides to alter the level of gene expression in a focal brain region targeted through a cannula. The study showcases a powerful approach to the functional genomic manipulation of a wild vertebrate species.

Keywords: Supergene, Phenotypes, ESR1, Genomic

Background

Genetic and genomic analyses of wild species have revealed that supergene regions can control variation in important ecological phenotypes. In such regions, alleles at multiple genes are co-inherited, typically because of structural rearrangements, including inversions, preventing meiotic recombination between different variants of the genome region. Alleles essentially cannot be exchanged between the two different chromosomes in heterozygotes. For example, alternative variants of supergene regions that link allelic differences at tens to hundreds of protein-coding genes determine wing patterns in butterflies1, colony organization in fire ants2, monkeyflower ecotypes3, and reproductive strategies in the ruff, a wading bird4.

A major challenge for understanding how supergenes evolve is disentangling how individual genes within a supergene region contribute to the overall supergene-encoded phenotype. This is because tight linkage of loci within a supergene impedes approaches based on genetic mapping (which relies on recombination). Even if good candidate genes are identified, functional genomic approaches are typically difficult or impossible in wild species.

Pioneering work in the white-throated sparrow Zonotrichia albicollis has shown that allelic differences in the sequence of one particular gene contribute substantially to the supergene-controlled phenotype in this species5. In white-throated sparrows, two alternative variants of a large, two-million-year-old supergene region control whether the bird’s head has a white or a tan-colored stripe. The two bird morphs also display alternative reproductive strategies, differing in territoriality, parental care investment and singing frequency. Both color morphs occur in both sexes, and there is strong disassortative mating, such that birds mate only with birds of the other color morph (and sex). Partly for this reason, this species has been said to effectively have four distinct “sexes” (see legend to Figure 1).

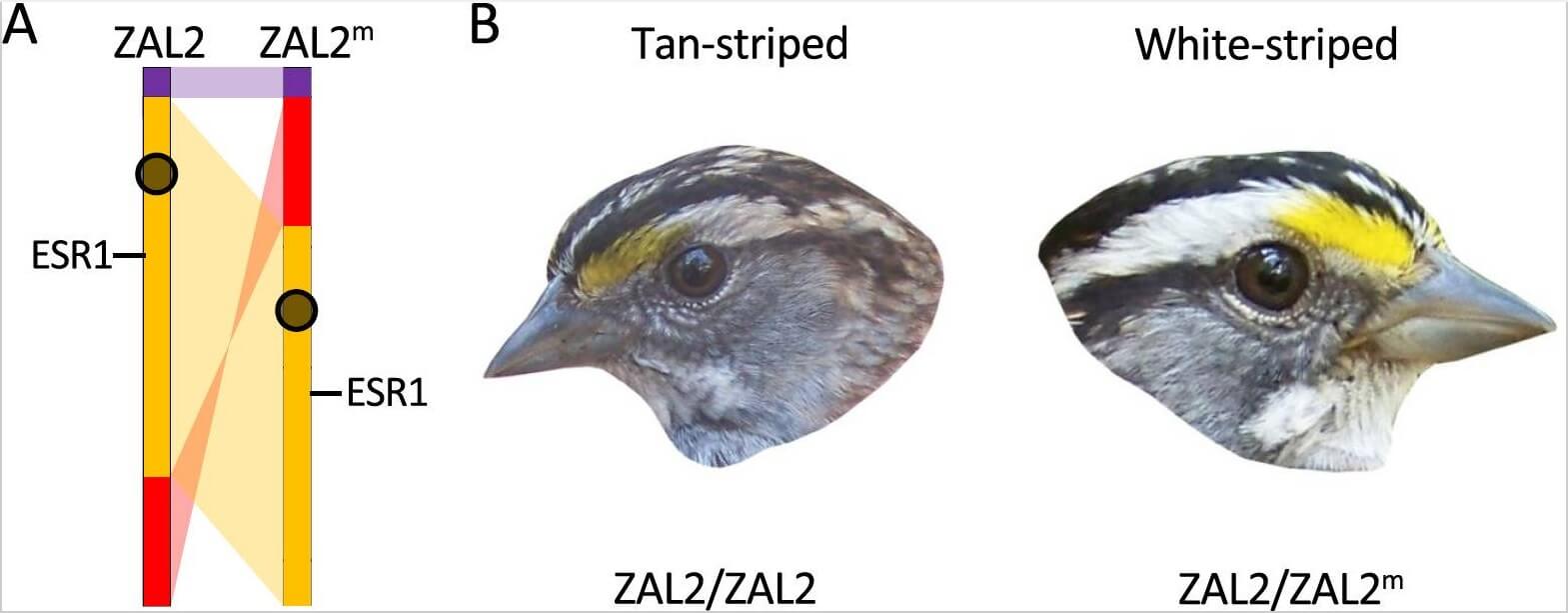

Figure 1.

The supergene region and the two color morphs of white-throated sparrows

A. The supergene region of the white-throated sparrow. There are two allelic variants of chromosome 2 in white-throated sparrows: ZAL2 and ZAL2m. The supergene covers two regions, indicated in orange and red, that differ in order and orientation between ZAL2m and ZAL2. This difference in orientation interferes with pairing and thus recombination between homologous regions. Normal pairing occurs on the rest of the chromosome (a small region adjacent to the inversion is shown in purple). The ESR1 gene is within the supergene region. Centromeres are shown as black circles (modified from Thomas et al.12 Fig 2). B. Birds carrying two copies of ZAL2 – that is, that are homozygous for ZAL2 – are tan-striped; heterozygous birds – those carrying one copy of ZAL2 and one copy of ZAL2m – are white-striped. Some of the behavioral differences between the two morphs are controlled by allelic differences at ESR1 (not shown). This system, in which a phenotypic trait – the color of the stripe – directs mating between homozygotes and heterozygotes, can be seen as analogous to mating between homogametic (in humans, XX) and heterogametic (in humans, XY) individuals. Thus, because mating can also only occur between females and males, these birds are sometimes said to have four sexes. Extending the parallel, there is also some evidence for degeneration (loss of genetic information) in the ZAL2m variant, and compensatory changes (dosage compensation) in homozygotes7 – changes that are characteristic of sex chromosomes, and that are also seen in the Sb fire ant supergene variant11. (Panel B is a derivative of Fig 1. from Horton et al.13, reproduced under a creative commons licence).

Main contributions and importance

This landmark study shows how some of the behavioral differences between white-striped and tan-striped sparrows are controlled by supergene-linked allelic differences at ESR1, the gene encoding estrogen receptor α. Among the approximately 1,000 protein-coding genes in the supergene region, ESR1 is a particularly attractive candidate for two reasons. First, it is central to an important endocrine pathway and can be manipulated pharmacologically. Second, estrogen was already implicated in the differences in aggressive behavior of the two morphs: white-striped sparrows are more aggressive than tan-striped sparrows in defense of their territory, and previous work had shown that administering estrogen elicits aggressive behavior in white-striped, but not in tan-striped, birds6. To explore how ESR1 may contribute to the phenotypic differences, the authors combine cutting-edge molecular techniques with established knowledge as to how and where estrogen signaling may affect territorial behavior.

They find that white-striped sparrows have several-fold higher expression levels of ESR1 than tan-striped sparrows, specifically in part of the amygdala (the nucleus taeniae, or TnA), but not in other brain regions. The authors confirmed that this difference in gene expression is controlled by the supergene variants as opposed to environmental factors because it is established even before hatching, and the alternative ESR1 promotor sequences drive different levels of reporter gene expression in cell lines. But the authors go beyond correlation to demonstrate causation.

For this, they reduced ESR1 mRNA levels in white-striped birds by introducing antisense oligonucleotides through a cannula to target the TnA region of the brain. After behavioral assays designed to test the aggressive response to territorial encroachment by another bird, they apply blue dye through the same cannula to check whether the TnA region was successfully affected. Remarkably, when the delivery succeeded, the aggressive behavior of white-striped birds became essentially indistinguishable from the behavior of tan-striped birds. In this trait at least, these white-striped birds now behave like tan-striped birds. Importantly, estrogen treatment did not increase aggression of white-striped birds in which ESR1 gene expression had been reduced experimentally. Tying these results together, the increased expression of ESR1 in the TnA of white-striped birds is due to DNA sequence differences in the regulatory region of the gene; this higher gene expression increases their sensitivity to estrogen, explaining their stronger territorial defense behavior.

This paper provides a rare causal demonstration of how one of many genes in a supergene region contributes to the phenotypic effect of a supergene, and a rare example of functional genomics of behavior in a wild vertebrate.

Open questions

The work by Meritt et al. begins to link together the major molecular building blocks of a textbook supergene system, setting the stage for further examination of how it functions and how it evolved.

Differential sensitivity to estrogen can affect multiple behavioral and physiological phenotypes, but it is unlikely to explain all the differences between the morphs. The supergene region includes many additional sequences that differ between the two supergene versions, and genes whose expression differs between morphs7. Correlations between behavior and expression levels have been shown, for example, for one of these genes, encoding a neuropeptide that can affect aggression and parental behavior8. Other genes within the supergene region presumably control differences in plumage color and mating preference.

Several questions remain open on the mechanism of estrogen sensitivity. For example, what are the transcription factors that modulate quantitative differences in ESR1 gene expression through their divergent cis-regulatory regions? And what are the downstream pathways through which differing levels of ESR1 expression translate to different behaviors?

From an evolutionary perspective, the major outstanding question for this and other supergene systems remains how selection could favor the suppression of recombination across almost an entire chromosome, given that this genomic architecture limits how selection can act9. In theory, a genomic rearrangement that suppresses recombination can be favored if it alters the activity of a single gene in a manner that confers a fitness benefit that outweighs the costs10. However, supergenes are typically thought to evolve mainly when selection favors particular combinations of alleles at two or more loci. Given that strong disassortative mating is a major phenotypic characteristic of the supergene system in the white-throated sparrow and is crucial for its maintenance, it is tempting to speculate that this trait, along with the stripe that determines mating preference, was critical for the evolution of suppressed recombination.

Furthermore, we do not know which phenotypic differences existed when the supergene system emerged, and which subsequently became controlled by supergene variants. It is possible, for example, that supergene variants did not differ initially at the ESR1 gene. Instead, balancing selection on alternative reproductive tactics could have favored ESR1 divergence after recombination ceased. Alternatively, pre-existing variation at ESR1 could have been locked in place when the supergene system emerged. Examining ESR1 diversity in extant populations of this and related species could help answer some of these questions.

Finally, follow-up work will clarify which of the other genes in the supergene region contribute to phenotypic differences between white-striped and tan-striped birds. There is evidence for degeneration (loss of genetic information) in the ZAL2m variant, and compensatory changes (dosage compensation7) – changes that are characteristic of Y and W sex chromosomes, and that are also seen in the Sb fire ant supergene variant11. These patterns may suggest that many of the genes in the supergene region have only negligible impact on phenotypic differences between tan-striped and white-striped birds.

Conclusion

The demonstration that ESR1 is a major effector of a supergene mediated phenotype in the white-throated sparrow makes this a landmark study for behavioral genetics and for understanding supergene evolution in a wild species. We look forward to the further disentangling of building blocks of complex supergene-encoded phenotypes in this and other species.

References

-

Joron M, Frezal L, Jones RT, Chamberlain NL, Lee SF, Haag CR, Whibley A, Becuwe M, Baxter SW, Ferguson L, Wilkinson PA, Salazar C, Davidson C, Clark R, Quail MA, Beasley H, Glithero R, Lloyd C, Sims S, Jones MC, Rogers J, Jiggins CD, ffrench-Constant RH: Chromosomal rearrangements maintain a polymorphic supergene controlling butterfly mimicry Nature 2011; 477 : 203 – 6 . 10.1038/nature10341

-

Wang J, Wurm Y, Nipitwattanaphon M, Riba-Grognuz O, Huang YC, Shoemaker D, Keller L: A Y-like social chromosome causes alternative colony organization in fire ants Nature 2013; 493 : 664 – 8 . 10.1038/nature11832

-

Lee YW, Fishman L, Kelly JK, Willis JH: A Segregating Inversion Generates Fitness Variation in Yellow Monkeyflower (Mimulus guttatus) Genetics 2016; 202 : 1473 – 84 . 10.1534/genetics.115.183566

-

Küpper C, Stocks M, Risse JE, Dos Remedios N, Farrell LL, McRae SB, Morgan TC, Karlionova N, Pinchuk P, Verkuil YI, Kitaysky AS, Wingfield JC, Piersma T, Zeng K, Slate J, Blaxter M, Lank DB, Burke T: A supergene determines highly divergent male reproductive morphs in the ruff Nature Genetics 2016; 48 ( 1 ): 79 – 83 . 10.1038/ng.3443

-

Merritt JR, Grogan KE, Zinzow-Kramer WM, Sun D, Ortlund EA, Yi SV, Maney DL: A supergene-linked estrogen receptor drives alternative phenotypes in a polymorphic songbird Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2020; 117 : 21673 – 80 . 10.1073/pnas.2011347117

-

Merritt JR, Davis MT, Jalabert C, Libecap TJ, Williams DR, Soma KK, Maney DL: Rapid effects of estradiol on aggression depend on genotype in a species with an estrogen receptor polymorphism Hormones and Behaviour 2018; 98 : 210 – 8 . 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2017.11.014

-

Sun D, Huh I, Zinzow-Kramer WM, Maney DL, Yi SV: Rapid regulatory evolution of a nonrecombining autosome linked to divergent behavioral phenotypes Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2018; 115 : 2794 – 9 . 10.1073/pnas.1717721115

-

Horton BM, Michael CM, Prichard MR, Maney DL: Vasoactive intestinal peptide as a mediator of the effects of a supergene on social behaviour Proceedings. Biological Sciences 2020; 287 : 20200196 . 10.1098/rspb.2020.0196

-

Charlesworth D: The status of supergenes in the 21st century: recombination suppression in Batesian mimicry and sex chromosomes and other complex adaptations Evolutionary Applications 2015. 9 ( 1 ): 74 – 90 . 10.1111/eva.12291

-

Kirkpatrick M, Barton N: Chromosome Inversions, Local Adaptation and Speciation Genetics 2006; 173 : 419 – 34 . 10.1534/genetics.105.047985

-

Martinez-Ruiz C, Pracana R, Stolle E, Paris CI, Nichols RA, Wurm Y: Genomic architecture and evolutionary antagonism drive allelic expression bias in the social supergene of red fire ants Elife 2020; 9 : e55862 10.7554/eLife.55862

-

Thomas JW, Cáceres M, Lowman JJ, Morehouse CB, Short ME, Baldwin EL, Maney DL, Martin CL: The chromosomal polymorphism linked to variation in social behavior in the white-throated sparrow (Zonotrichia albicollis) is a complex rearrangement and suppressor of recombination Genetics 2008; 179 : 1455 – 68 . 10.1534/genetics.108.088229

-

Horton BM, Hauber ME, Maney DL: Morph matters: aggression bias in a polymorphic sparrow PLoS One 2012; 7 : e48705 . 10.1371/journal.pone.0048705